Michael Darcy

The standard of care for managing renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is surgical resection, whereas in nonsurgical candidates, small RCCs are commonly treated with percutaneous ablation. So even though embolization of RCC has been around since the initial description in 1973,1 its role is still relatively limited. However, in certain situations, it can be a very useful technique.

DEVICE DESCRIPTION

Catheters needed for embolization are generally not exotic. Standard 5-Fr catheters such as Cobra or Sos-shaped catheters are adequate to engage the main renal artery. If the RCC involves only a portion of the kidney, a microcatheter can be used to advance closer to the tumor’s vasculature. Because coils are rarely used and particles or liquid embolics are favored, microcatheters with larger internal diameters can be useful. Occasionally, if the embolization is to be carried out from the main renal artery and the artery is short, a balloon occlusion catheter can be used to help prevent reflux of embolic materials.

The choice of embolic agent depends somewhat on the goal of the embolization. If you are simply providing preoperative devascularization, occluding the major arterial branches is adequate. Thus, large particles or even coils can be used to rapidly occlude the arteries. If embolization is the definitive therapy, then one wants to occlude very small peripheral branches to maximize the percentage of tumor tissue that undergoes necrosis. The fact that arteriovenous fistulae may sometimes be present in an RCC may guide the selection of embolic agents because particles or liquids could rapidly pass through the fistula.

Particles such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) are favored by some because they are readily available, relatively inexpensive, and easy to use. Suspending the PVA in contrast allows fluoroscopic monitoring to ensure that the particles are injected where intended. The size of the particles selected depends on the goal of embolization. Larger particles can easily occlude the major branches and reduce flow for preoperative devascularization. To achieve complete tissue necrosis for definitive therapy, smaller particles (100 to 300 µm) are a better choice.

Alcohol is favored by many because it will penetrate into peripheral small branches, thus reducing the chance of any collateral perfusion keeping the tumor alive. The problem is that alcohol is not radiopaque and therefore more difficult to use. As outlined in Chapter 9, mixing ethanol with Ethiodol provides opacification so the injections can be fluoroscopically monitored. It has an added benefit of allowing more peripheral embolization. Pure ethanol causes spasm, immediate protein denaturation, and thrombus formation. Mixing ethanol with Ethiodol blunts this effect and allows the ethanol to penetrate further into the precapillary arteries.2 Although alcohol can be delivered through a peripherally positioned end-hole catheter, balloon occlusion catheters are favored when alcohol needs to be injected into the main renal artery. This is to prevent reflux from the renal artery into the abdominal aorta. Cyanoacrylate glue or Onyx (Covidien, Irvine, California) can also be used, but the expense of these agents cannot be justified given how easy it is to embolize an RCC with these other less expensive agents.

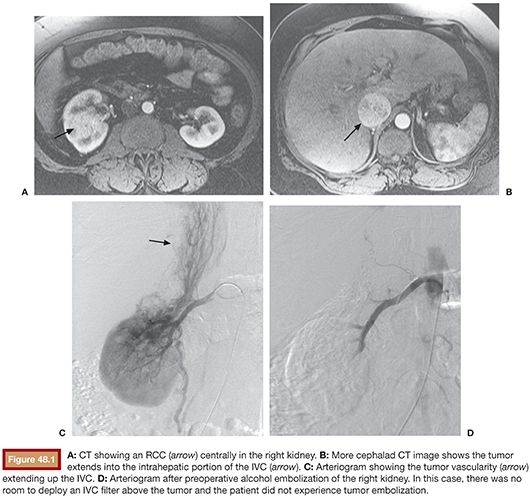

TECHNIQUE

There are several considerations before starting an embolization for RCC. Preoperative antibiotics are often used to reduce the chance of abscess formation in the necrotic tumor. Although renal embolization can be done with local anesthesia and sedation, general anesthesia should be considered if ethanol is going to be used (especially in larger volumes) because it can be painful. For large tumors extending into the renal vein or inferior vena cava (IVC), one concern is that embolization-induced necrosis will cause the tumor thrombus to become detached and embolize to the heart. Placing a suprarenal IVC filter has been used as a way to protect against embolization.3 In some cases, the tumor thrombus may extend too far into the IVC and there may not be enough room to deploy a filter without extending into the right atrium. In that setting, we have still embolized the kidney and have not seen tumor embolization (Fig. 48.1), although that is still a concern. Use of a large self-expanding stent has been described to hold the tumor against the IVC wall to prevent embolization.4 This has the added benefit of restoring caval patency. However, this technique would primarily be useful during palliative embolization because stenting across the tumor would interfere with a surgical resection. Finally, one may need to address a renal artery stenosis first to allow easier catheterization of the renal artery or to help preserve function of the normal parenchyma.5

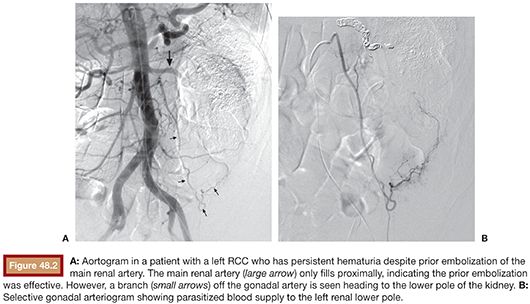

An effective embolization always starts with a good diagnostic arteriogram. Although preprocedure cross-sectional imaging will often indicate the number of major renal arteries supplying the kidney, one can miss small accessory renal arteries that might supply the tumor. Also, RCCs can parasitize blood supply from surrounding structures. Thus, diagnostic arteriography is needed to discover all the potential sources of blood supply to the tumor. This is best accomplished with a flush aortogram so that all vessels supplying the tumor will be opacified. Alternatively, in cases of very large RCCs with tortuous and distorted vascular anatomy, it may be difficult to see small arteries supplying the RCC because of overlapping larger vessels. Thus, it may be easier to identify smaller arteries supplying the RCC if you first embolize the major vessels supplying the tumor and then perform an aortogram to search for those vessels (Fig. 48.2).

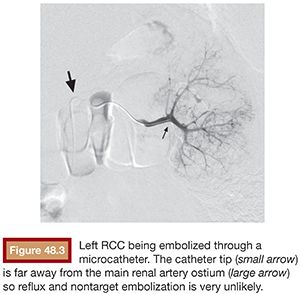

Catheter choice depends on individual patient anatomy. For RCCs involving only a portion of the kidney, microcatheters are used for superselective catheterization to preserve as much normal renal parenchyma as possible. But even for large RCCs that will require embolizing the whole kidney, some prefer to use microcatheters because positioning them very peripherally in the kidney reduces the chance of reflux and nontarget embolization (Fig. 48.3). The downside to microcatheters for larger tumors is that you have to selectively catheterize multiple branches. When dealing with a large RCC that occupies most of the kidney, it is often more expeditious to embolize from a more proximal position in the main renal artery. It is important to make sure the catheter is positioned far enough into the main renal artery to avoid infusing embolic material into the adrenal arteries (Fig. 48.4), which could cause adrenal dysfunction or hypertensive crisis. When using a balloon occlusion catheter, an initial contrast injection is done with the balloon inflated to see what volume of contrast is needed to fill the renal artery. This is done to gauge how much ethanol needs to be injected. For preoperative devascularization, some interventionalists prefer to just catheterize the main renal artery, inject some PVA peripherally, and then deposit coils in the main renal artery. One caveat is that coils should not be placed too proximally in the renal artery because that can interfere with effective clipping or ligation of the main renal artery during nephrectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree