Fig. 11.1

(a) Thrombosis within the great saphenous vein in a transverse view through the thigh in a symptomless patient. There were no signs of periphlebitis. The fascial structures are recognisable as well as the connective tissue in the subcutaneous fat. (b) Thrombosis within the great saphenous vein in a longitudinal view in the same patient. (c) Transverse view through the thigh of the same patient further down the leg. Thrombus is seen in the great saphenous vein and a venous tributary which still lies deep to the fascia. It is important to determine if the superficial vein thrombosis within a perforating vein extends into the deep system. (d) Same position as (c) with colour duplex demonstrating partial flow around the thrombus

Copyright: [Author]

Localised hardness with pain: Characteristically there is a coagulum in the vein with inflammation of the vein wall. Clinically, the vein is indurated with a brownish discolouration and the course of the vein is painful when pressed. The brown areas may be accompanied by reddening confined to the course of the vein. The ultrasound image is similar to patients without pain (Fig. 11.1).

Superficial reddening with hardness and pain: Coagulum in the vein with periphlebitis defines this condition. Severe pain occurs when the area is pressed. Examination is not easily tolerated and the skin appears red and inflamed. In the ultrasound image, the thrombosis is accompanied by loss of the typical structure of the subcutaneous fatty tissue which appears homogeneous (Fig. 11.2). Occasionally there is a surrounding inflammatory halo of oedema. Compression testing (Fig. 11.3) is very painful and should only be done to exclude thrombosis with extension into the deep veins (Fig. 11.4).

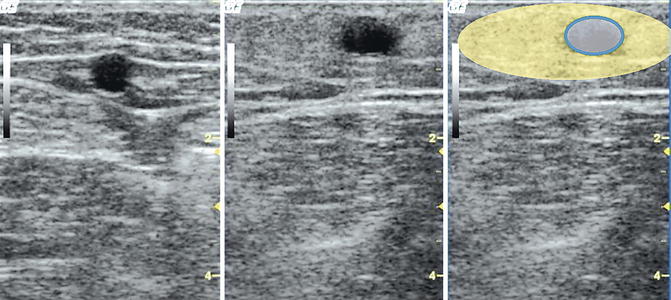

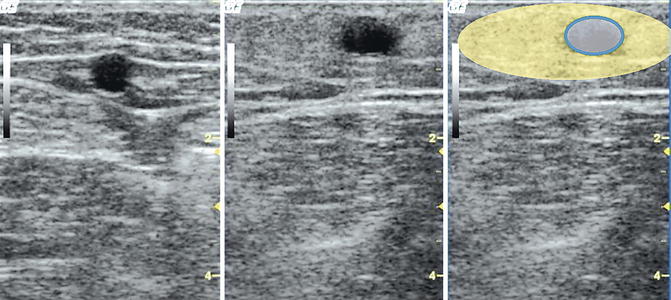

Fig. 11.2

Patient with pain and redness of the inner thigh. Left: transverse view of the mid-thigh above the painful area. The great saphenous vein is compressible and the fascial structures are preserved. Middle: transverse view further down and at the painful region. A thrombosed venous tributary is identified which is not compressible. The fascial structures in the subcutaneous tissue are no longer recognisable and the surrounding tissue appears grey and homogeneous. Right yellow: the subcutaneous fatty tissue has lost its architecture. Blue: thrombosed vein

Copyright: [Author]

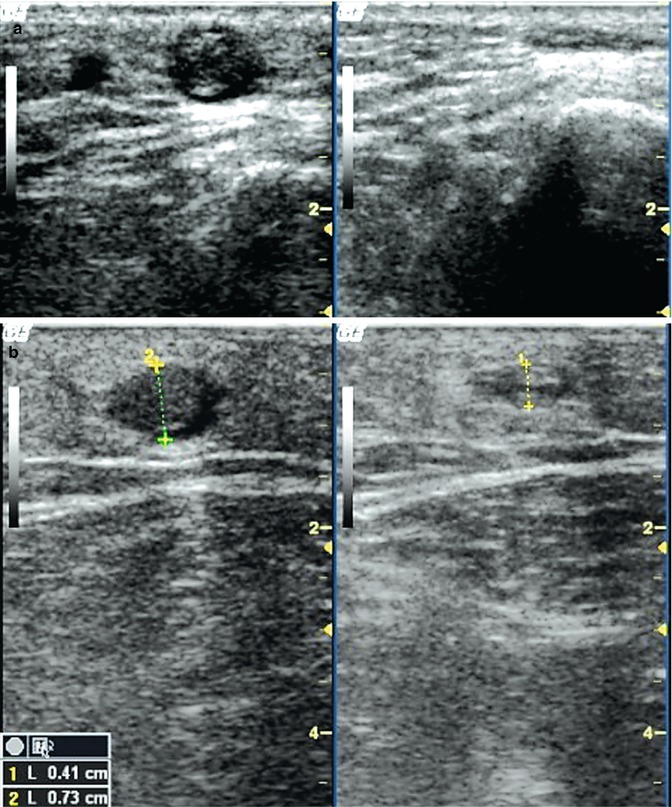

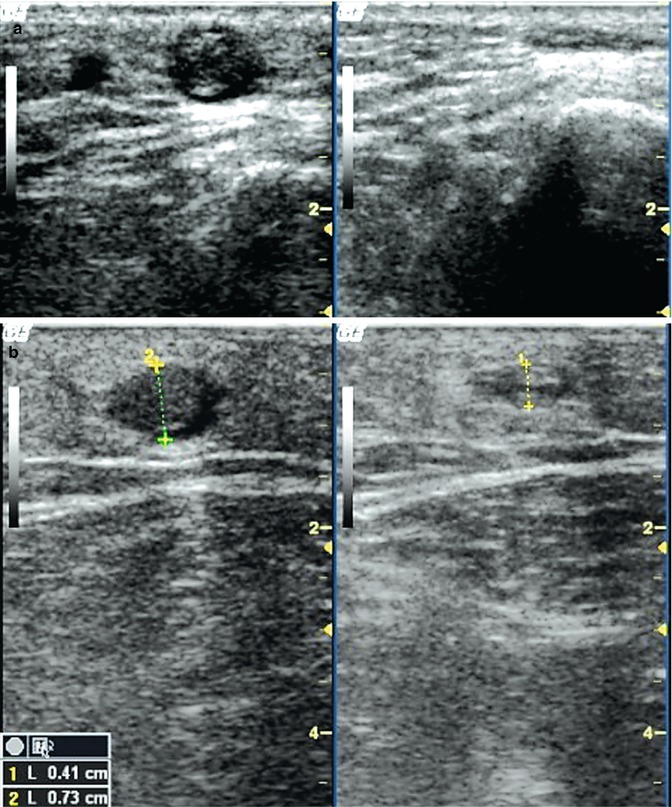

Fig. 11.3

Compression testing in superficial vein thrombosis. (a) Transverse view through the proximal section of the calf with an asymptomatic superficial vein thrombosis of the venous tributary, left without compression, right with compression: The great saphenous vein cannot be seen under compression. The venous tributary is smaller and only the echo-rich luminal material remains visible. There is preservation of the fascial architecture with no inflammation of the surrounding tissues (periphlebitis) (see accompanying online material). (b) Same patient as in Fig. 11.2 in transverse view through the thigh further down the leg. The coagulum appears more voluminous in the B-scan without compression than under compression. A periphlebitis is seen with loss of definition of the surrounding subcutaneous tissues. Compression is very painful (see accompanying online material)

Copyright: [Author]

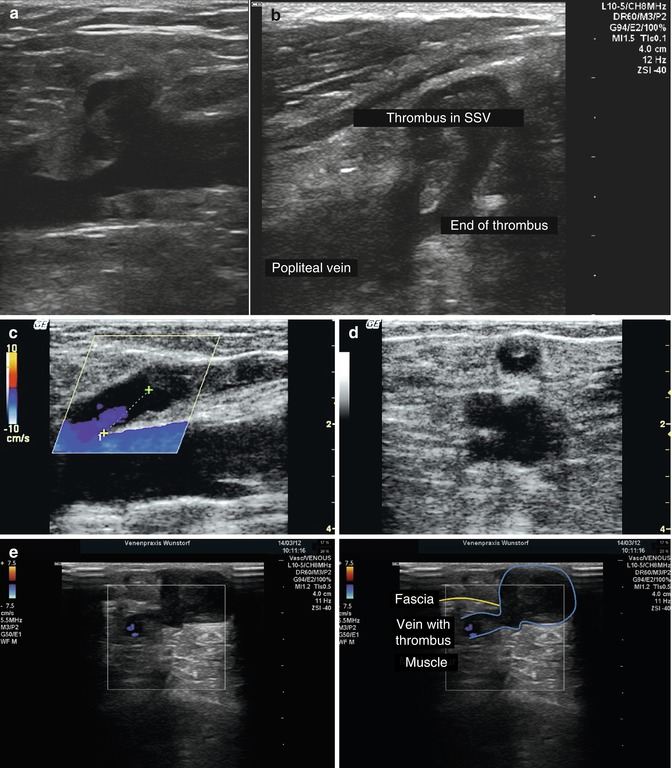

Fig. 11.4

Superficial vein thrombosis extending into a perforating vein. This occurred in a patient with pain in the inner calf after a football injury. Longitudinal view of the inner calf with a superficial vein thrombosis in a paratibial perforating vein demonstrating partial flow around the clot (see accompanying online material)

Copyright: [Author]

A characteristic of thrombus in the saphenous veins is that it can extend into the deep veins through several junctions. This condition is called ascending superficial vein thrombosis. The saphenous vein must be examined carefully up to its confluence with the deep vein. The end of the thrombus is best seen in longitudinal view (Fig. 11.4).

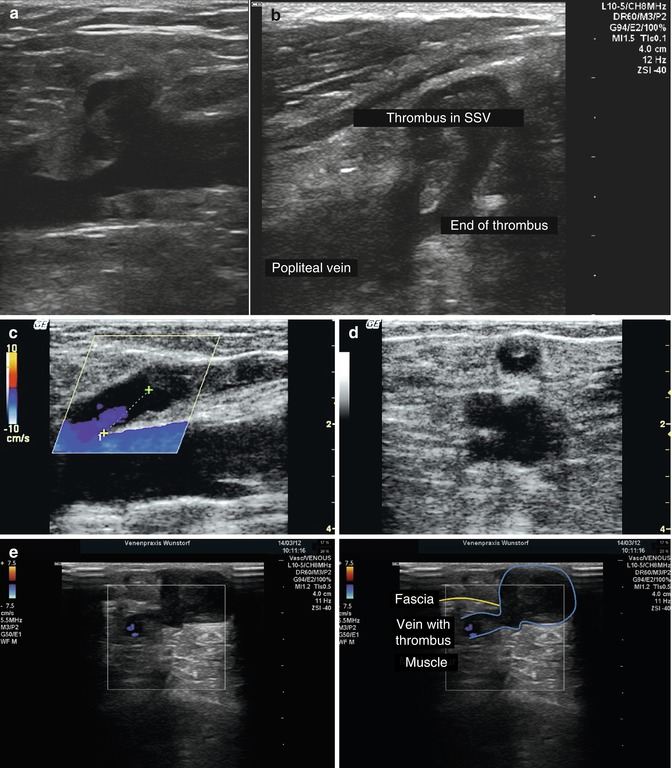

A superficial vein thrombosis may protrude into the deep veins where it becomes surrounded by flow without any attachment to the wall of the vein. This is called a floating thrombus. Until a few years ago, such a finding would have indicated immediate ligation of the saphenofemoral junction as an emergency. Today, more conservative measures are preferred which includes compression, therapeutic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin or oral anticoagulants (e.g. warfarin) and frequent check-ups as an outpatient. The patient must be told of the danger of a pulmonary embolism and is given the same information as outpatients who are treated for a deep vein thrombosis. Thrombus may also spread from the saphenous veins or, more frequently, from a venous tributary through perforating veins (Fig. 11.5e). Thrombotically altered veins must therefore be examined by ultrasound over their whole course and any perforation of the fascia should be tested with compression ultrasound for thrombotic material.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 11.5

Ascending superficial vein thrombosis. (a) Longitudinal view of the great saphenous vein through the left groin demonstrating thrombus protruding slightly into the common femoral vein. The thrombus appears interrupted because of flow draining the venous tributaries of the saphenofemoral junction. The image in the accompanying online material is further lateral showing the thrombus extending from the great saphenous vein into the deep vein. This is diagnosed as a partially occluding deep vein thrombosis. (b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree