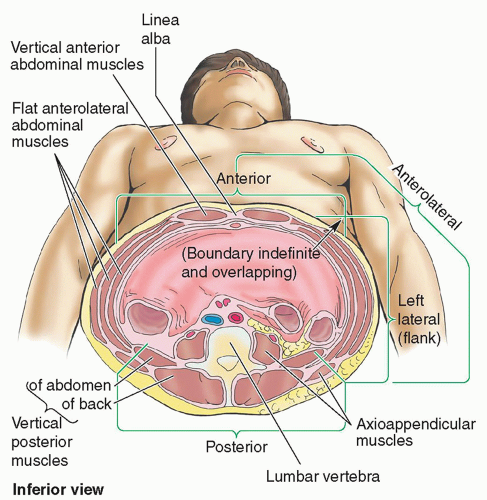

The anterolateral wall extends from the thoracic cage to the pelvis. Superiorly, it is bounded by the cartilages of the 7th to 10th ribs and the xiphoid process. Inferiorly, it is bounded by the inguinal ligament and iliac crests, pubic crests, and pubic symphysis of the pelvic bones.

6,7

Layers

When describing abdominal wall anatomy, it is important to distinguish between fascia and aponeuroses. A fascia is a fibrous tissue network located between the skin and the underlying structures. It is richly supplied with both blood vessels and nerves. The fascia is composed of two layers: a superficial layer and a deep layer. The superficial fascia is attached to the skin and is composed of connective tissue containing varying quantities of fat. The deep fascia is loosely connected to the superficial fascia by fibrous strands. The deep fascia covers the muscles and partitions them into groups. Although the deep fascia is thin, it is more densely packed and is stronger than the superficial fascia; however, neither the superficial fascia nor the deep fascia possesses any notable internal strength because they are a condensation of connective tissue organized into definable homogeneous layers within the body.

7,8Aponeuroses are layers of flat tendinous fibrous sheets fused with strong connective tissue that attach muscles to fixed points, functioning like a tendon, so they are quite strong. Aponeuroses have minimal vascularity and innervation. The abdominal wall aponeuroses are primarily located in the ventral abdominal regions with a primary function to join muscles to the body parts that the muscles act upon. The most readily known abdominal aponeurosis is the rectus sheath.

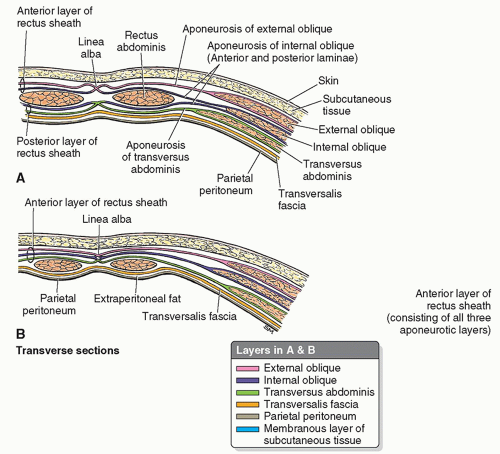

7,8The abdominal wall appears as a laminated structure when viewed in cross section.

7 From superficial to deep, the layers include the following: (1) skin, (2) subcutaneous tissue (superficial fascia), (3) muscles and their aponeuroses, (4) deep fascia, (5) extraperitoneal fat, and (6) the parietal peritoneum.

4,6,7 The skin attaches loosely to most of the subcutaneous tissue except at the umbilicus where the attachment is firm.

4,8The subcutaneous tissue anterior to the muscle layers makes up the superficial fascia. Superior to the umbilicus,

it is consistent with that found in most regions. In contrast, inferior to the umbilicus, the deepest part of the subcutaneous tissue is reinforced with elastic and collagen fibers and is divided into two layers. The first is a superficial fatty layer (Camper fascia) containing small vessels and nerves. Camper fascia gives the body wall its rounded appearance. The second layer is a deep membranous layer (Scarpa fascia) and it consists of a combination of fat and fibrous tissue that blends with the deep fascia.

4,8 The membranous layer continues into the perineal region as the superficial perineal fascia (Colles fascia)

4 (

Fig. 4-5).

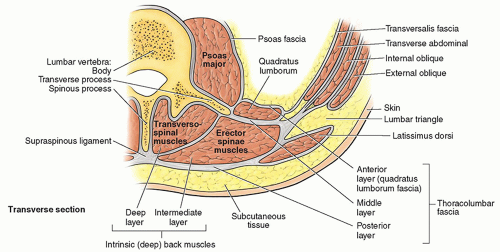

The three anterolateral abdominal muscle layers and their aponeuroses are covered by superficial, intermediate, and deep layers of extremely thin investing fascia.

4,8 The investing layer of fascia is located on the external aspects of the three muscle layers and is not easily separated from the external muscle layer, the epimysium. Varying thicknesses of membranous and areolar sheets of endoabdominal fascia line the internal aspects of the wall. Although the endoabdominal fascia is continuous, different regions are named based on the muscle or aponeurosis it lines. For example, the portion lining the deep surface of the transversus abdominis muscle and its aponeurosis is the transversalis fascia. Internal to the endoabdominal fascia is the parietal peritoneum. The distance separating the parietal peritoneum from the endoabdominal fascia is determined by the variable amounts of extraperitoneal fat in the fascia.

4 The parietal peritoneum is the outer layer of the serous membrane lining the abdominopelvic cavity formed by a single layer of epithelial cells and supporting connective tissue

4 (see

Fig. 4-5).

Muscles

There are five bilaterally paired muscles in the anterolateral abdominal wall and one unpaired muscle (

Table 4-1). Located bilaterally on the anterior abdominal wall are the rectus abdominis muscles (see

Fig. 4-4). The rectus abdominis is a long, broad, vertical, strap-like muscle that is mostly enclosed in the rectus sheath. Also located on the

anterior abdominal wall in the rectus sheath is the pyramidalis muscle. The pyramidalis, a small triangular muscle, extends from its base, originating on the pubic bone to its apex inserting into the midline linea alba approximately halfway between the pubic symphysis and the umbilicus. This muscle lies deep to the anterior rectus fascia and superficial to the rectus abdominus muscle. The pyramidalis muscle is present in about 80% to 90% of people and can be easily harvested for use in reconstructive surgery when needed. Its function is poorly understood, but it helps to maintain tension on the linea alba, supporting the tone of the anterior abdominal wall

4,6,9 (

Fig. 4-6).

There are three flat, bilaterally paired muscles of the anterolateral group. From superficial to deep, they include the following layers: (1) the external oblique, (2) the internal oblique, and (3) the transversus abdominis

4,6 (see

Fig. 4-4 and

Table 4-1). Coupled with the vertical orientation of the fibers of the rectus abdominis, the fibers in the three flat muscles are arranged to provide maximum strength by forming a supportive muscle girdle that covers and supports the abdominopelvic cavity. In the external oblique, the muscle fibers have a diagonal inferior and medial orientation. The fibers of the internal oblique, the middle muscle layer, have a perpendicular orientation at right angles to those of the external oblique, running from lateral-inferior to superior-medial. The fibers of the innermost muscle layer, the transversus abdominis, are oriented transversely or horizontally, like a belt encircling the abdomen.

4,6

Structures

The other structures within the anterolateral abdominal wall include the rectus sheath, linea alba, umbilical ring, and the inguinal canal.

The rectus sheath is a strong, dense connective tissue fascia that encases the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles as well as some arteries, veins, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. The anterior and posterior layers of the rectus sheath are formed by the intercrossing and interweaving of the aponeuroses of the flat abdominal muscles. Additionally, each belly of the rectus abdominus muscle is divided into four sections by intersecting fascia, forming the “six-pack” that is visible on some people with highly toned abdominal

muscles. At the lateral aspect of the rectus sheath, the aponeuroses fuse to form the linea semilunaris, which demarcates the interface of the rectus abdominus with the internal and external oblique and transversus abdominus muscles.

4,8 The posterior rectus sheath ends at the arcuate line, located halfway between the umbilicus and the pubis symphysis. The inferior, or distal, quarter of the rectus abdominus muscle is covered posteriorly by the transversalis fascia, which is all that separates the rectus muscles from the parietal peritoneum in the pelvic region

10 (

Fig. 4-7A, B).

The linea alba (or white line) is a midline, dense connective tissue structure that separates the right and left bellies of the rectus abdominus muscle. It is a fusion of the aponeuroses that form the rectus sheath.

4,10The linea alba extends from the xyphoid process to the pubic symphysis. Superiorly, the linea alba is wider and it narrows inferior to the umbilicus to the width of the pubic symphysis. The linea alba transmits small vessels and nerves to the skin (

Figs. 4-4,

4-6A, and

4-7A, B). In thin, muscular people, a groove is visible in the skin overlying the linea alba.

The umbilicus is the area where all layers of the anterolateral abdominal wall fuse.

4 The umbilical ring is a defect in the linea alba located deep to the umbilicus.

4 This is the area through which the fetal umbilical vessels passed into the umbilical cord to connect with the placenta. The umbilicus and umbilical ring are the remnants of that fetal connection.

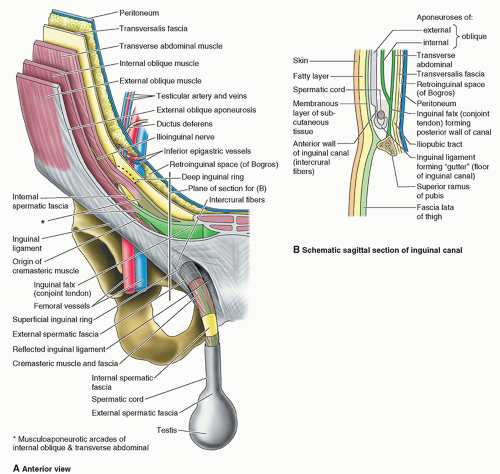

The inferior border of the external oblique aponeurosis extends between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle forming the inguinal ligament.

10 Located in the inguinal region superior and parallel to the medial half of the inguinal ligament is the inguinal canal, a passageway through the abdominal wall that is formed during fetal development. It is an important canal where structures exit and enter the abdominal cavity, and the exit and entry pathways

are potential sites of herniation.

4,10,11 In adults, the inguinal canal is an oblique passage approximately 4 to 6 cm long. Functionally and developmentally distinct structures located within the canal are the spermatic cord in males and the round uterine ligament in females. Other structures included in the canal in both sexes are blood and lymphatic vessels and the ilioinguinal and genital nerves.

10 The entrance of the inguinal canal is formed by the deep inguinal ring at the superior end. The superficial (external) inguinal ring forms the exit at the inferior end. Normally, the inguinal canal is collapsed anteroposteriorly against the spermatic cord or round ligament. Between the two openings (rings), the inguinal canal has two walls (anterior and posterior), a roof, and a floor

10,11 (

Table 4-2 and

Fig. 4-8A, B).