The interstitial pneumonias (IPs), or idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), are a heterogeneous group of diffuse lung diseases characterized by varying degrees of lung inflammation and fibrosis. They are best thought of as reactions to lung injury, presenting with specific histologic patterns. They are loosely unified by several characteristics including clinical presentation, radiographic manifestations, and pathologic appearance and may be idiopathic or associated with specific diseases. In this chapter, we intend to provide a general understanding of the IPs and the idiopathic clinical disorders with which they may be associated.

CLASSIFICATION

The IPs were originally classified by Liebow in the 1960s. They have been redefined and reclassified several times as an understanding of their patterns has been refined. While some of the terms in the original classification have remained the same, others have been changed or deleted. For instance, giant cell IP was part of the original classification of IPs, but has since been recognized to be a specific entity, namely hard metal pneumoconiosis; it is no longer considered an IP.

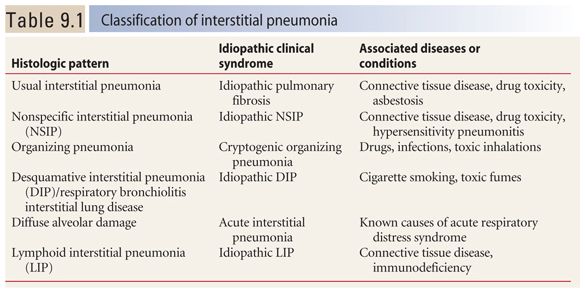

It is important to recognize that the IPs are defined as histologic patterns and not diseases. Each pattern may be the result of an idiopathic clinical syndrome (thus representing an IIP) or may be associated with a specific disease, and not be idiopathic. The current classification is shown in Table 9.1.

The IPs include usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP), and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP). DIP, along with respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD), is usually related to smoking and is also discussed in Chapter 11. LIP is best thought of as a lymphoproliferative disorder that will be discussed in detail in Chapter 17.

HRCT IN THE IPs

In the interpretation of HRCT in a patient with a suspected IP, it is important to understand the relationship between the imaging pattern and the pathology and clinical syndrome present. In classic cases, the HRCT pattern may be used to predict the pathologic pattern.

Take, for example, UIP. When classic findings of UIP are present on HRCT (i.e., we say a “UIP pattern” is present), there is a high degree of certainty that a surgical lung biopsy will also show UIP. However, several different diseases may be associated with a UIP pattern. If idiopathic, UIP is considered to represent idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). On the other hand, UIP may be associated with connective tissue diseases, drug toxicity, and asbestosis. These may be indistinguishable radiographically and pathologically. Clinical correlation is important in distinguishing the various causes of a UIP pattern.

The IPs are a common cause of diffuse lung disease and should be considered as a possible etiology whenever a patient has chronic symptoms or findings of fibrosis or lung infiltration on HRCT. The HRCT findings vary depending upon the degree of inflammation or fibrosis that is present. Cases that are predominantly inflammatory result in ground glass opacity and consolidation. Cases that are predominantly fibrotic are associated with irregular reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and/or honeycombing.

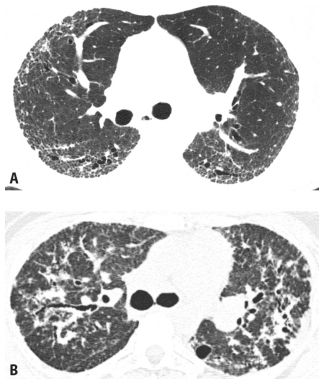

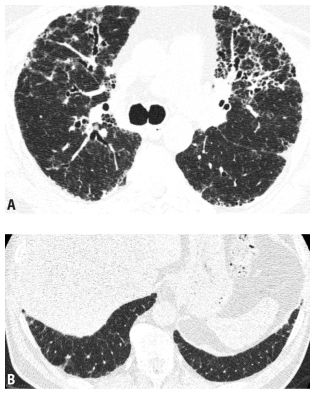

Most of the IPs present at the extremes of this spectrum (Fig. 9.1A, B), although there may be significant components of both inflammation and fibrosis present in selected cases. UIP is a pattern characterized predominantly by fibrosis. NSIP may be fibrotic, cellular, or a combination of both. The remaining IPs are predominantly inflammatory, although they may show progression to fibrosis in some cases.

Distribution can be helpful in distinguishing the IPs from alternative causes of diffuse lung disease (Fig. 9.2A, B). UIP, NSIP, and DIP often demonstrate a subpleural predominance of abnormalities, with involvement of the lung bases, including the costophrenic angles. Other causes of diffuse lung disease, such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), are often diffuse or central in axial distribution and show sparing of the inferior costophrenic angles.

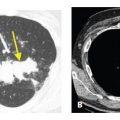

Figure 9.1

Inflammation versus fibrosis on HRCT. The interstitial pneumonias present with varying degrees of inflammation and fibrosis. Two patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia from connective tissue disease are depicted. A. HRCT shows ground glass opacity without definite signs of fibrosis, representing potentially reversible inflammatory abnormalities. B. HRCT shows fibrosis as manifested by traction bronchiectasis (arrows) and irregular reticulation. These findings reflect irreversible lung scarring that would be unresponsive to treatment.

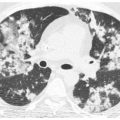

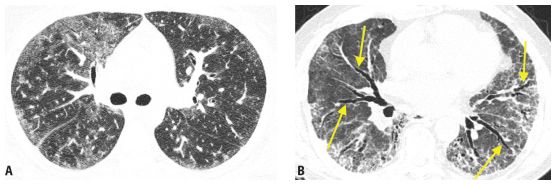

Figure 9.2

Distribution of HRCT abnormalities in diagnosis. A. In this patient with fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) related to scleroderma, HRCT shows a peripheral and subpleural predominance of abnormalities. B. HRCT in a patient with sarcoidosis shows central and peribronchial abnormalities, with relative sparing of the subpleural lung. In the setting of chronic symptoms, a subpleural and basilar predominance of abnormalities suggests usual interstitial pneumonia, NSIP, or desquamative interstitial pneumonia. A diffuse or central axial distribution is atypical for an interstitial pneumonia and suggests alternative diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis or sarcoidosis.

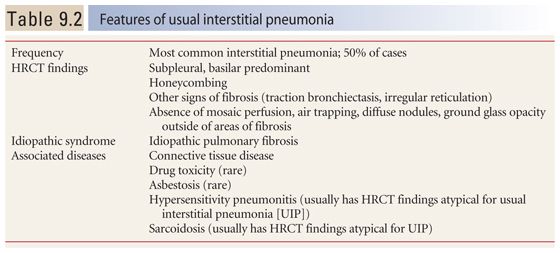

USUAL INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

UIP (Table 9.2) is common and accounts for approximately 50% of cases of IP. Pathologically, patients with UIP have irreversible fibrosis with heterogeneous involvement of the lung. Areas of normal lung are intermixed with areas of end-stage fibrosis. As UIP represents irreversible fibrosis, affected lung regions do not show improvement with immunosuppressive medications.

The most common disease associated with UIP is IPF, but there are several specific diseases that may also result in this pattern.

HRCT Findings

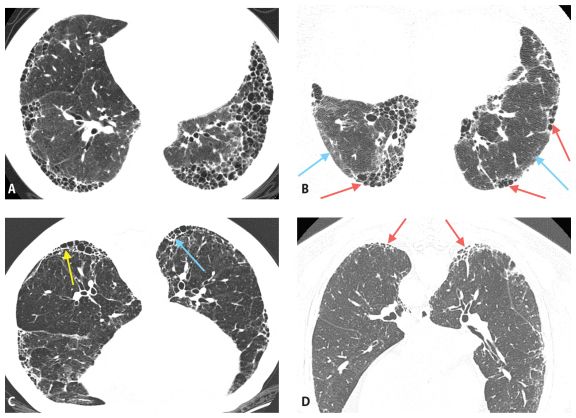

In patients with UIP, HRCT typically shows reticulation with a subpleural and basilar predominance. The reticular opacities are often irregular in appearance. Traction bronchiectasis is often associated with the reticular opacities. Honeycombing is present in about 70% of cases and is critical in making a definite diagnosis of UIP (Fig. 9.3A–D). Honeycombing results in the presence of clustered, cystic airspaces, with well-defined walls, usually 3 to 10 mm in diameter, and predominating in the subpleural lung. As with the overall extent of abnormalities, honeycombing, when present, is most severe and extensive at the lung bases (Fig. 9.4A–E).

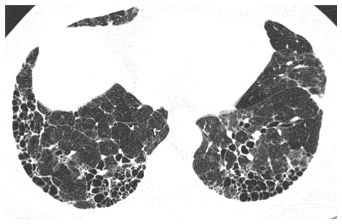

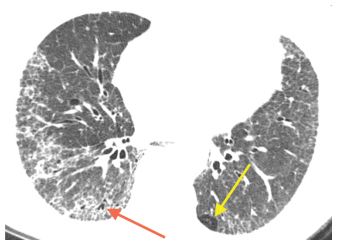

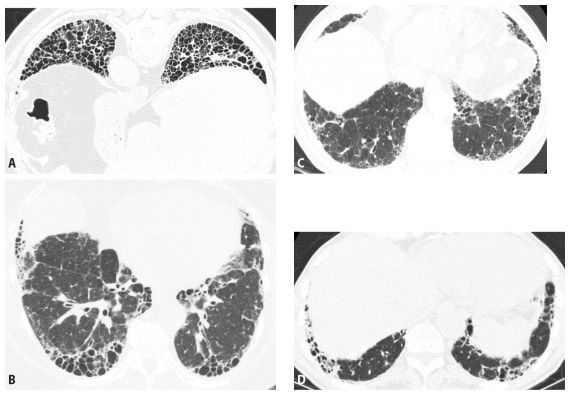

Figure 9.3

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). A. Extensive subpleural and basilar predominant honeycombing is noted in a patient with a UIP pattern associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. B. Subpleural honeycombing (red arrows) is present in a patchy distribution. This is interspersed with areas of relatively normal lung (blue arrows). C. Prone HRCT shows honeycombing (arrows) in a patient with UIP. Honeycombing may be in a single (yellow arrow) or multiple (blue arrow) layers. D. Early UIP shows mild subpleural reticulation and honeycombing. A confident diagnosis of honeycombing (arrows) can be made in this case despite the mild abnormalities.

In patients with early or mild UIP, only reticulation or reticulation with traction bronchiectasis is visible on HRCT. With progressive or severe lung involvement, honeycombing is also present.

Ground glass opacities are common in UIP, but are less extensive than areas of fibrosis. Ground glass opacity is usually seen in lung regions that also show findings of fibrosis (i.e., reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, or honeycombing) and, in UIP, typically reflects the presence of microscopic fibrosis.

Although the upper lobes are usually abnormal in patients with UIP, findings of fibrosis predominate in the lung bases, and the posterior costophrenic angles are almost always involved. The findings of fibrosis are often patchy in distribution, but involve the posterior and subpleural lung to the greatest degree.

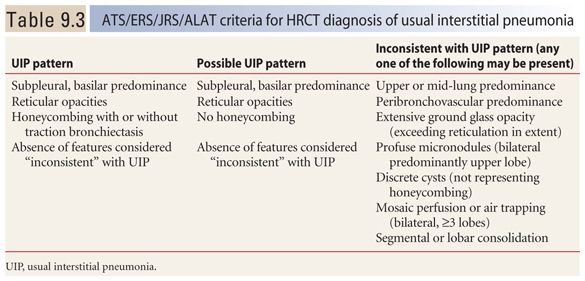

When typical HRCT findings of UIP are present on HRCT, the appearance is termed a UIP pattern. According to criteria recently agreed upon by American, European, Japanese, and Latin American societies (Table 9.3), the HRCT diagnosis of a UIP pattern can be based on (1) the presence of a basal and subpleural predominance of abnormalities, (2) reticular opacities, (3) honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis, and (4) an absence of findings inconsistent with this diagnosis. This combination of findings predicts a pathologic diagnosis of UIP in 95% to 100% of cases. However, keep in mind that not all cases of UIP will meet these criteria. These criteria are specific, but likely not very sensitive.

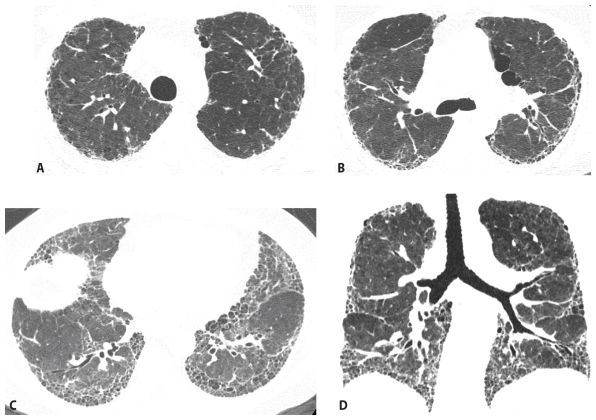

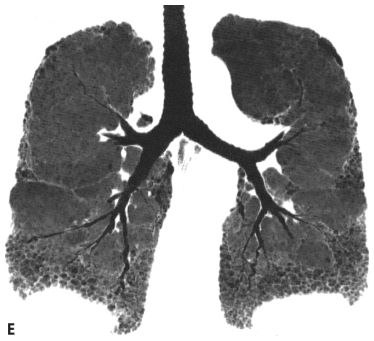

Figure 9.4

Usual interstitial pneumonia, distribution. HRCT images through the aortic arch (A), tracheal carina (B), and lung bases (C) show a peripheral and basilar predominance of honeycombing. Coronal reformat (D) and coronal minimum intensity projection (E) images confirm the basilar distribution of disease.

A possible UIP pattern is based on all of these, but without honeycombing being present.

HRCT findings that are considered inconsistent with a UIP pattern include (1) an upper or mid-lung predominance of abnormalities, (2) a peribronchovascular predominance of abnormalities, (3) extensive ground glass opacity, exceeding reticulation in extent, (4) profuse micronodules, bilateral, and upper lobe, (5) discrete cysts, not representing honeycombing, (6) mosaic perfusion or air trapping, bilateral, and in three or more lobes, and (7) segmental or lobar consolidation. Each of these findings is typical of an IP other than UIP or a different lung disease. Any one of these is sufficient for determining if the HRCT is inconsistent with a UIP pattern (see Figs. 9.12–9.15).

When HRCT findings are considered diagnostic of a UIP pattern, the differential diagnosis includes IPF (Fig. 9.5A), connective tissue disease (Fig. 9.5B), asbestosis (Fig. 9.5C), and drug toxicity (Fig. 9.5D). These are often indistinguishable on HRCT and may be difficult to differentiate pathologically.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

IPF is a common cause of diffuse fibrotic lung disease and is the most common cause of a UIP pattern (Fig. 9.6).

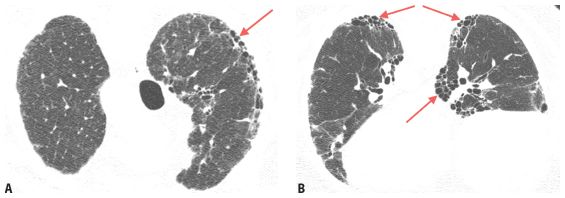

Figure 9.5

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), differential diagnosis. Four examples of UIP on HRCT are shown. Subpleural, basilar predominant fibrosis with honeycombing is seen in patients with UIP secondary to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (A), connective tissue disease (B), asbestosis (C), and drug toxicity (D). When presenting with a UIP pattern, these diseases are often indistinguishable on HRCT.

Figure 9.6

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A typical usual interstitial pneumonia pattern is present, manifested by patchy subpleural honeycombing. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is the most common cause of this pattern.

A patient with idiopathic UIP has IPF. If a patient with a UIP pattern on HRCT has a disease or exposure that is known to be associated with this pattern (e.g., collagen disease and asbestos exposure), by definition, the diagnosis cannot be IPF. Also, there are fibrotic lung diseases, other than IPF, in which the clinical history may not be contributory. This is particularly true with other idiopathic disorders such as sarcoidosis and diseases that may not have an identifiable exposure, such as HP. HRCT often allows the correct diagnosis is such cases.

IPF primarily affects patients over 50 years of age. It is progressive and patients have a poor prognosis, with a 50% 3-year survival. The disease is usually unresponsive to traditional immunosuppressive treatments. Clinical trials are underway to determine the efficacy of other drugs in arresting the progression of lung disease in patients with IPF.

The diagnosis of IPF, in many cases, is based solely upon a combination of clinical information and typical HRCT findings (i.e., a “UIP pattern”). Lung biopsy is not usually performed unless the HRCT findings are interpreted as “possible UIP” or “inconsistent with UIP” or the patient’s clinical history suggests an alternative diagnosis.

In the absence of any clinical or radiographic findings to suggest an alternative diagnosis, a patient with a UIP pattern on HRCT will be given a presumptive diagnosis of IPF (Fig. 9.7). As a HRCT may be considered diagnostic of IPF without a biopsy, it is important to be conservative in diagnosing a definite UIP pattern.

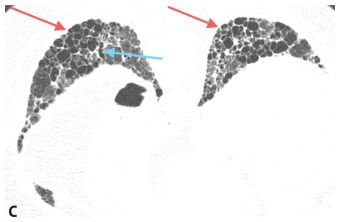

Figure 9.7

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). HRCT images through the upper (A), mid (B), and lower (C) lungs show a subpleural and basilar predominance of honeycombing (red arrows) and traction bronchiectasis (blue arrow) compatible with usual interstitial pneumonia. In the absence of known diseases or exposures, this patient will be given a diagnosis of IPF.

Figure 9.8

Nonspecific pattern of fibrosis. HRCT shows peripheral fibrosis with irregular reticulation and mild traction bronchiectasis (red arrow). Minimal mosaic perfusion is present (yellow arrow), but no honeycombing is seen. This pattern is not diagnostic of any particular disease and biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis.

Keep in mind that not all cases of IPF show typical HRCT findings. Despite that, however, HRCT remains extremely important in making this diagnosis. Even if lung biopsy is interpreted as “UIP,” a clinical diagnosis of UIP cannot be made with certainty if HRCT is interpreted as inconsistent with this diagnosis (Fig. 9.8). It has been recommended that in such a case, a careful consideration of all data by a multidisciplinary group of lung disease experts is necessary.

Atypical HRCT manifestations of IPF include (1) fibrosis that is not subpleural and basilar predominant (Fig. 9.9A, B), (2) predominant ground glass opacity (Fig. 9.10), and (3) focal areas of mosaic perfusion or air trapping (Fig. 9.11A, B).

Patients with IPF may show slow or rapid progression of their disease, with a progressive increase in findings of fibrosis. Patients with IPF also may present with an acute worsening of their symptoms. This is termed acute exacerbation of IPF. HRCT in such patients usually shows ground glass opacity involving areas previously affected by fibrosis or previously unaffected regions of lung (Fig. 9.12A–C). The ground glass opacity typically represents DAD.

Figure 9.9

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), atypical distribution. This patient with IPF and biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) shows atypical findings, with fibrosis that is not subpleural predominant and has significant involvement of the central lung regions (A). Also, there is relative sparing of the costophrenic angles (B). Atypical manifestations of IPF are not uncommon. On the basis of HRCT, this case would be read as “inconsistent” with UIP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree