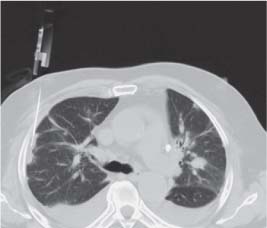

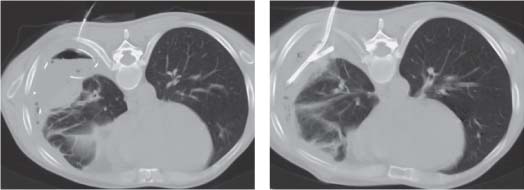

14 Thoracic Intervention Radiologic interventions are minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures which may be performed under ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or fluoroscopic guidance. The following interventions will be discussed: Diagnostic fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core biopsy can provide cytologic, histologic, and microbiologic information on pulmonary, pleural, chest wall, and mediastinal lesions. FNA and core biopsy of pulmonary and mediastinal lesions are usually performed under CT guidance whereas more superficial lesions of the pleura and chest wall sometimes may be biopsied under ultrasound guidance. The imaging procedure must define clearly the biopsy needle path, the target lesion, and surrounding critical structures. When ultrasound guidance and a transcostal approach are used, the needle is introduced at the superior rib margin to protect the intercostal arteries. For biopsy of pulmonary and mediastinal lesions, CT is employed to accurately localize the target lesion and the biopsy needle can be advanced under CT/CT-fluoroscopic guidance avoiding surrounding vessels and other critical structures (Fig. 14.1). It is easiest for the patient to keep still when imaging is performed at functional residual capacity or in slight inspiration. Histologic and cytologic specimens are acquired from solid lesions. Spring-loaded 18-gauge cutting needles (TruCut type) are most commonly used (Fig. 14.2). Fig. 14.1 CT-guided biopsy of area of subpleural opacification using 18G TruCut needle. Fig. 14.2 CT-guided biopsy of left upper lobe lesion with patient in prone position and using 18G TruCut needle. The inner needle with specimen notch has been advanced into the lesion. The outer cutting sheath has not yet been deployed. Fine needle diagnostic or therapeutic aspirates may be taken from fluid collections. The needle gauge depends on the viscosity of the fluid contents. A small pneumothorax is commonly seen after percutaneous lung biopsy with a reported incidence of 25–30%. Most of these, however, resolve spontaneously and needle aspiration and/or percutaneous tube drainage are required in just a small number of cases. Biopsy-related pulmonary hemorrhage and hemoptysis may also occur. Percutaneous needle aspiration and catheter drainage is employed for treatment of pleural effusion, empyema, and pneumothorax. It is usually performed under local anesthesia. Prerequisites include a clear anatomical drainage path and a discrete well-defined collection which has not become significantly loculated. Simple needle aspiration may be sufficient or a catheter may be inserted using a “direct” or Seldinger technique and this may be left in-situ for a few days until adequate drainage has occurred (Fig. 14.3a, b). Fig. 14.3a, b CT-guided drainage of pleural empyema using Seldinger technique. Fig. (a) shows guidewire which has been advanced through the introducer needle into the collection. Fig. (b) shows correct placement of 12F pigtail catheter. Pleural effusions and empyemas in many cases may be visualized sufficiently well with ultrasound to allow ultrasound-guided drainage. CT-guided drainage may be performed if the collection cannot be visualized adequately with ultrasound due to its small size, anatomic position, or due to large patient body habitus. Collections containing significant amounts of gas may also be better visualized with computed tomography. These procedures are usually performed under local anesthesia. Potential complications include hemorrhage and infection. Foreign bodies in the major systemic veins, right heart, and pulmonary arteries may reflect fragments which have become detached from venous catheters. Other foreign bodies include fragments of puncture sets, guidewires, pacemaker leads, and embolization materials from treatment of arteriovenous shunts. These foreign bodies tend to become lodged in the right atrium, superior vena cava, and left pulmonary artery. For percutaneous retrieval to be feasible the foreign body must be radiographically visible and it must be possible to “mechanically” grasp the object under fluoroscopic visualization. The object should not have been present long enough to allow endothelialization and vascular adhesion to occur. The potential for complications from the foreign body should be weighed against the risk of its retrieval. The standard technique involves femoral venous access and use of a large-bore sheath. If the foreign body has been present for some time, diagnostic angiography should be performed to exclude secondary thrombus. Otherwise the retrieval may be preceded by lytic therapy. The preferred instrument is a gooseneck snare, which is maneuvered over one end of the foreign body under fluoroscopic guidance and tightened so that it forms a U-shaped loop when withdrawn. The retrieval catheter and snared foreign body are withdrawn into the sheath and extracted with it (Fig. 14.4a, b). The alternative use of a forceps catheter carries a higher risk of vessel wall injury and does not grasp the object as securely as the snare.

Biopsy

Clinical Features and Indications

Contraindications

Technique

Complications

Drainage

Clinical Features and Indications

Contraindications

Technique

Complications

Foreign Body Retrieval-Extraction

Clinical Indications

Contraindications

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree