George M. Bridgeforth and John Cherf

A 49-year-old man slipped and fell on the ice. He now complains of severe right knee pain. He has marked difficulty weight-bearing on the right knee.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Trauma to the knee may result in a tibial plateau fracture.

- It is necessary to check for a compartment syndrome (markedly swollen calf with neurovascular impairment).

- Patients may have an associated fibular head fracture (swelling, bruising, pain, and soreness) with or without a peroneal nerve palsy.

Clinical Presentation

Tibial plateau fractures involve the tibial plateau, or the upper surface of the tibia (Fig. 15.1). The most common mechanism of injury is axial loading that might result from a fall or a direct blow, usually to the outside of the knee. Sometimes tibial plateau fractures are called “bumper” fractures, because they may result from impact with automobile bumpers. Normally, patients have a recent history of trauma to the knee area. Older people may fall, and younger people may injure themselves playing sports. They may be unable to bear weight on the injured knee. Symptoms include pain, joint stiffness, and swelling. A knee effusion typical.

A knee fracture or a severe knee contusion is characterized by acute swelling, ecchymosis, focal tenderness, and impaired range of motion (especially if the fracture extends to the articular surface of a joint). These signs always point the examiner to the injured area. The differential diagnosis of tibial plateau fractures also includes damage to the collateral ligament, medial or lateral meniscus, or anterior or posterior cruciate ligament. Several tests may be used to determine the actual problem. In an acute setting with high-impact trauma, the patient may have marked swelling, guarding, and apprehension, which may make it difficult to perform these tests.

A medial or collateral ligament tear is characterized by pain, tenderness, and swelling with valgus (medial collateral ligament) or varus (lateral collateral ligament) laxity. Collateral ligament instability should be checked with the knee in slight (30 degrees) flexion. When the knee is fully extended, an anatomic rotation automatically locks the knee in place medical. Collateral ligament instability is tested by stabilizing the knee with one hand and applying inward pressure against the knee while slowing pulling the lower extremity outward away from the body. With a medial collateral ligament tear, the valgus instability is characterized by the inward (medial) deviation of the knee with an outward deviation of the lower extremity. The instability is caused by a torn medial collateral ligament. With a lateral collateral ligament tear, the opposite effect occurs. There is varus instability, which is reflected by outward displacement of the knee when pressure is applied from an inward to outward direction. Moreover, it is associated with inward deviation of the lower extremity (toward the body) as the lower extremity is pulled inward by the examiner.

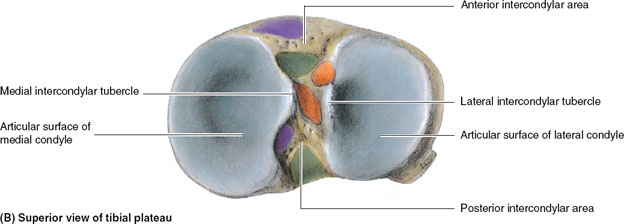

FIGURE 15.1 The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) extends from the anterior intercondylar region of the tibia to the medical surface of the lateral condyle of the femur. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) extends from the posterior intercondylar region to the lateral medial condyle of the femur. Fractures of the tibial plateau may result in associated injuries to the ACL, PCL, and the menisci. (From Moore, Dalley AF II. Clinical Oriented Anatomy. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.)

Standard tests for a medial or lateral menisci tear may be pain limited. A McMurray test is performed by stabilizing the knee with one hand and the lower extremity with the other. The knee is flexed and then externally rotated. Next, the knee is gradually straightened. Pain at the medial joint line that occurs either with external rotation or while the externally rotated leg is straightened is considered positive for a medial meniscus tear. Pain at the lateral joint line with internal rotation indicates a lateral meniscus tear. In addition, the Apley compression test may be positive. The patient lies face down, and the examiner places both hands around the ankle region and applies downward pressure. Pain with compression indicates a torn meniscus. (Patients with a torn meniscus also have trouble squatting.) It should be noted that in a patient with a large effusion with a tibial plateau fracture, the standard stability tests are limited by marked swelling, pain-limited range of motion, apprehension, and guarding. In these instances, cross-table lateral radiographs may be helpful. If there is a large effusion or if the patient exhibits a fat-blood interface (looks like an air–fluid level), then the examiner should suspect intra-articular pathology such as a condylar fracture, a fracture of the median eminence, or a torn cruciate ligament.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Pain and swelling

- Possible knee effusion

- Pain with limited range of motion

- Antalgic gait

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree