Chapter 109 Overview: Benign lymphoid hyperplasia is believed to represent a benign condition of the bowel and is most frequently found in the distal ileum and in the colon. These lesions represent patches of lymphoid tissue and can be seen in both adults and children. The precise prevalence in children is unknown, but the entity has been found in up to 30% of symptomatic patients undergoing colonoscopy.1 Etiology: A number of possible causes have been postulated. The observation of benign lymphoid hyperplasia in families suggests that genetic or environmental factors could be pertinent.2 A recent study by Krauss et al.3 found that the prevalence of lymphoid hyperplasia at colonoscopy also is high in adults, and they postulated that it may relate to an enhanced immune response. In children, a number of theories have been proposed, including a local response to infection, immunodeficiency states, and local hypersensitivity reaction. Controversy also exists regarding the association of benign lymphoid hyperplasia and the autism spectrum disorder.4 Clinical Presentation: Benign lymphoid hyperplasia is usually discovered incidentally either on imaging or at endoscopy. As such, it is almost certainly underrecognized, and its true prevalence is unknown. Visual inspection at colonoscopy will demonstrate multiple raised, closely spaced areas along the bowel wall. Imaging: The appearance on imaging studies is that of innumerable small filling defects, mostly uniform in size, at times umbilicated, and most commonly seen on double-contrast imaging of the colon (Fig. 109-1). These lesions are often too small to be detected on a single-contrast examination. One of the earliest imaging descriptions stressed their benign nature and the need to distinguish the lesion from true polyps,5 citing instances in which colectomies were performed because the benign nature of these lesions was not recognized. This pattern of innumerable small lesions (often in the range of 2 to 3 mm) also should be distinguished from benign lymphoid polyps, which are more common in adults and can become fairly large and pedunculated.6 Figure 109-1 Benign lymphoid hyperplasia. Overview: A number of vascular lesions and vascular tumors can arise within the colon. They are rare in children but can have specific clinical settings and imaging findings, which can allow for a specific diagnosis. Some vascular lesions will be found incidentally. Others can present as lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract bleeding. Etiology: Vascular lesions of the colon represent a wide array of conditions. The etiology is known for some lesions and remains unknown for others. Colonic varices (particularly in the rectal region) can be seen as mural lesions and typically are seen with portal hypertension, providing a collateral pathway between the portomesenteric and the systemic venous systems. This collateral pathway has been reported to occur in nearly one third of children with portal hypertension. In that group of patients, significant rectal bleeding was seen in 7%.7 Other vascular lesions also can result in lower GI bleeding. Venous malformations, arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, telangiectasias, and hemangiomas all have been described in the colon in children but are rare.8 Their etiology is not well understood. Clinical Presentation: Because vascular lesions of the colon tend to come to light when they are symptomatic, the true incidence is unknown, but they are believed to be rare in children. The presentation can be that of lower GI bleeding or anemia. It should be noted that hemangiomas, which fall under the category of vascular tumors of the GI tract, can be associated with cutaneous hemangiomas in up to 50% of cases. Imaging: The lesions are difficult to resolve with most imaging modalities. Multidetector computed tomography (CT) with imaging in the early arterial phase after contrast injection can demonstrate these lesions. Involved bowel will show intense enhancement (Fig. 109-2). Some patients will have abnormal supplying arteries or draining veins visible on CT. In a minority of cases with bleeding, active extravasation can be visualized.9 Figure 109-2 Colonic infantile hemangioma. Treatment: Much like vascular lesions elsewhere in the GI tract and indeed elsewhere in the body, the treatment of the lesion depends on the specific lesion, its location, the degree and extent of involvement, and the clinical status of the patient. These lesions can be treated medically or surgically, embolized via a catheter, or sclerosed endoscopically. Although treatment very much depends on the type of lesion, some controversy exists with regard to the classification of intestinal vascular anomalies in children. Many persons advocate applying a classification system used for other vascular anomalies, such as the system proposed by Fishman and Mulliken,10 although other persons advocate use of a broader system.11 Overview: Juvenile or hamartomatous polyps are the most common intestinal tumors in childhood, with a prevalence of 1% to 3%. They may be single or multiple, and most are found in the sigmoid colon and rectum, but they can arise anywhere along the GI tract. Etiology: Histologically these lesions appear as mucus-filled glands, and they might be related to blocked, hyperplastic mucus glands. A dense infiltrate of inflammatory cells suggests an inflammatory inciting event, and thus the synonymous term “inflammatory polyp.” However, the underlying etiology of these isolated polyps remains to be determined. Clinical Presentation: Although presentation is rare in the first year of life, most patients present in the first decade, typically between 2 and 5 years of age. The most common presenting symptom is painless bright red rectal bleeding. Pain is associated with the rare complication of colocolic intussusception. Some children present with iron deficiency anemia. Others can present with a prolapsing mass, which can be mistaken for rectal prolapse.12 Imaging: In the past, investigation for colonic neoplasms such as the juvenile polyp in a child with rectal bleeding often included a double-contrast enema. On such an examination, these lesions are typically smooth and can be sessile or pedunculated; most measure 3 cm or less. Currently the diagnosis is more frequently made endoscopically or on cross-sectional imaging, in which the lesions appear as nonspecific intraluminal masses (Fig. 109-3). Figure 109-3 Juvenile polyp. Treatment: Because these solitary lesions carry no increased risk of malignancy, the treatment is polypectomy alone. Most commonly, a polypectomy is performed with snare resection during a colonoscopy. The anemia is treated with iron supplementation or transfusion if necessary. With resection of the polyp, the blood loss should cease. If multiple polyps are present or a family history of juvenile polyps is uncovered, then the patient should be evaluated for the juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), discussed later in this chapter. Although the inherited polyposis syndromes are rare, they have the potential to cause serious morbidity and mortality within affected families. A proper understanding of the various conditions is important for the primary clinician and consultant. Genetic screening and initiation of a surveillance plan is mandatory. Surveillance should include the GI tract as well as extraintestinal sites of potential disease.13 Overview: First described in the literature in 1964,14 JPS is an autosomal-dominant condition that is characterized by a multiplicity of GI hamartomatous polyps. It is the most common of the hamartomatous syndromes. Etiology: In approximately 75% of cases, a family history of the disease will be present. The condition also can occur sporadically as a result of new mutations. Mutations have been identified in the SMAD4 gene on chromosome 18 and the BMPR1A gene on chromosome 10.15 Clinical Presentation: From a clinical standpoint, the disease should be considered in any patient with five or more juvenile polyps in the colon, extracolonic juvenile polyps, or with any number of polyps when associated with a positive family history.16 The clinical presentation can be more variable than in the patient with nonsyndromic juvenile polyps. In addition to rectal bleeding, anemia, and intussusception, patients with JPS in whom there is involvement of a large segment of the GI tract can present with failure to thrive, malabsorption, or hypoalbuminemia. Associated congenital anomalies include hydrocephalus and hypertelorism. Small series have described JPS in association with other conditions, including hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.17 Imaging: The imaging appearance of polyps in JPS differs in the number of polyps identified, but otherwise it is similar to that of isolated lesions. Treatment: Patients with JPS have an increased risk of colonic malignancy that is reported to be as high as 50% on the basis of family studies.18 Screening of these children can be done with a combination of endoscopy, various imaging modalities, and capsule endoscopy. Polyps typically are removed via snare polypectomy. Overview: Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome with an estimated prevalence of 1 : 200,000 individuals.19 Features include hamartomatous polyps of the GI tract, hamartomatous lesions of the skin, hamartomas of other solid organs, and neoplasms of the breast, thyroid, and endometrium.19 GI tract polyps arising in these patients include inflammatory, hyperplastic, lipomatous, and even adenomatous lesions. Etiology: Cowden syndrome is one of several disorders that fall under the category of the protein tyrosine phosphatase and tensin (PTEN) hamartoma tumor syndromes. Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN are present in up to 80% of patients with Cowden syndrome.19,20 Clinical Presentation: The presentation of patients with Cowden syndrome can be similar to the other conditions in which colonic polyps occur. Patients with Cowden syndrome also have an increased risk of neoplasms of the thyroid, endometrium, and breast. The lifetime risk of breast cancer in women with Cowden syndrome is between 25% and 50%. In these women, the onset of breast cancer is earlier than in sporadic cases. At present, the risk of GI malignancy in these patients is unknown.19 Imaging: The imaging appearance of polyps in Cowden syndrome is similar to that of polyps described earlier in the chapter. Treatment: Polyps in patients with Cowden syndrome are treated with snare polypectomy; screening can include endoscopy, fluoroscopic and cross-sectional imaging modalities, and capsule endoscopy. Anemia is treated with iron supplementation and transfusion if necessary. Appropriate screening for the associated neoplasms also must be initiated. This screening consists of early breast self-examination and perhaps early initiation of mammography. Thyroid and uterine surveillance with screening ultrasound also is recommended.

Tumors and Tumorlike Conditions

Nonneoplastic Lesions

An 11-year-old girl had a double-contrast barium enema as part of the workup for rectal bleeding. A spot image of the descending colon from that examination demonstrates numerous filling defects that are uniform in size. The findings are consistent with benign lymphoid hyperplasia. Similar findings were seen throughout the colon.

Vascular Lesions

An infant presented at 4 weeks of age with gastrointestinal bleeding requiring multiple transfusions. An enhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis was done in the arterial phase. Axial (A) and coronal reconstruction (B) demonstrates intense enhancement of the wall of the distal ileum and cecum (arrows). Venous drainage is through a markedly dilated mesenteric vein (arrowhead in B). The affected segment was resected, and pathology confirmed that it was an infantile hemangioma.

Neoplastic Lesions

Juvenile Polyps

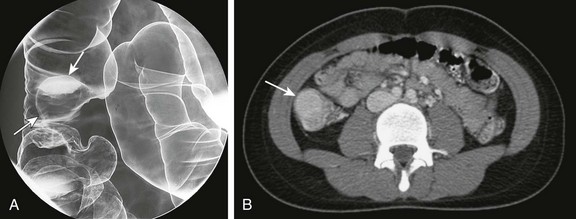

A 15-year-old girl presented with a 2-month history of abdominal pain. A, A double-contrast enema demonstrates a sessile mass consistent with a polyp arising from the wall of the ascending colon (arrows). B, A computed tomography scan in the same patient demonstrated an enhancing mass (arrow) within the lumen of the ascending colon.

Polyposis Syndromes

Syndromes Associated with Juvenile or Hamartomatous Polyps

Cowden Syndrome