George M. Bridgeforth and George Holmes

A 39-year-old man with schizophrenia presents with right ankle pain and swelling 10 days after a fall. He is unable to take four steps.

CLINICAL POINTS

- The majority of ankle fractures are unimalleolar.

- A unimalleolar fracture involves either the distal fibula (more common) or the distal tibia.

- Most oblique and spiral fractures (above the tibial plafond) are unstable.

Clinical Presentation

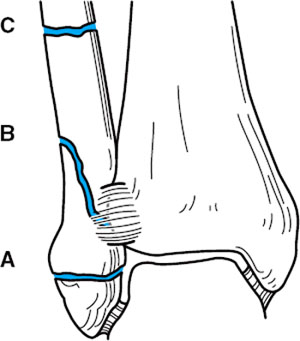

Ankle fractures are becoming increasingly common, and they account for approximately 10% of all fractures. About two-thirds of these injuries are unimalleolar fractures, which affect the distal fibula, or less commonly, the distal tibia (Fig. 21.1). Most unimalleolar fractures affect the distal fibula, but it is important to note that fractures below the distal tibial plafond (ceiling) are generally stable. This region is sometimes called the tibiotalar line. The talar dome is a curved structure supported on either side by two bony stirrups (the distal fibula and tibia) and surrounding collateral ligaments. Most fractures below the tibial plafond have sufficient surrounding structural support.

The surrounding supporting structures consist not only of the medial (distal tibia) and lateral malleolus (distal fibula) but also the supporting ligaments and joint capsule. The lateral collateral ligaments, which prevent excessive eversion of the ankle and joint dislocation, are formed by the anterior talofibular ligament, the posterior talofibular ligament, and the calcaneofibular ligament. The fan-shaped deltoid ligament is actually made up of four ligaments (the anterior tibiotalar ligament, the tibionavicular ligament, the tibiocalcaneal ligament, and the posterior tibiotalar ligament). The medial collateral ligaments help prevent excessive inversion and ankle dislocations.

The mechanism of injury is direct trauma. Inversion injuries involve the distal fibula, and eversion injuries involve the distal tibia.

In the introductory case, the patient has marked tenderness of the distal fibula and an inability to take four steps, thus meeting at least two of the Ottawa rules for the evaluation of ankle injuries (see Chapter 20). However, there is no tenderness of the navicular or fifth metatarsal, the third Ottawa criterion. The Ottawa rules have excellent sensitivity (well more than 90%) for the detection of acute fractures. For physicians who adhere strictly to the Ottawa rules, it is recommended that radiographs be obtained within 7 days if the patient does not show any signs of improvement; this may allow detection of a missed occult fracture. The absence of the Ottawa criteria may not completely rule out an acute fracture. Therefore, the examiner is advised to use his or her own discretion.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Pain, swelling, tenderness, and bruising

- Limited weight-bearing ability

- Limited range of motion

- Possible associated fractures

All patients with ankle injuries should be evaluated for more extensive and serious conditions depending on the history. Details about the causal incident, such as the direction of torque force applied to the ankle and the foot’s position, help predict the nature and severity of the ankle fracture. Patients do tend to remember the event, but they often cannot recall exactly how the fracture occurred. A thorough examination of the involved ankle is necessary. Symptoms and signs of fracture include pain, swelling, and tenderness of the medial and lateral malleolus, with possibly bruising and discoloration. Inability to bear weight indicates a fracture. There is pain-limited range of motion—dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion, or eversion.

FIGURE 21.1 Schematic diagram of the AO/OTA classification of ankle fractures. (A) There are three types of ankle fractures in the AO/OTA classification: type A, type B, and type C. Each type is further subdivided into three groups. (From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD. Rockwood & Green’s Fractures in Adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.)

To check for instability, the physician should use the anterior–posterior drawer test for instability. In addition, the physician should

- check varus (inversion) and valgus (eversion) strain for collateral ligament instability

- palpate the navicular and the fifth metatarsal should be palpated for associated foot fractures. Talar pain with dorsiflexion indicates a possible associated talar fracture.

- check the posterior tibia for a fracture of the posterior tibial lip for possible fracture.

- check for heel pain and tenderness, which may be signs of a fracture

- perform a neurovascular examination to check for coldness, pallor, diminished or absent pulses, and diminished or absent pinprick.

Patients with septic joints should have radiographs taken followed by a diagnostic aspiration. The treatment for septic joints is directed toward the underlying cause.

NOT TO BE MISSED

- Bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures

- Ankle sprains and contusions

- Collateral ligament tears

- Ankle cellulitis (soft tissue infection of the ankle not involving the joint space)

- Septic joint

- Gout

- Rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid changes in other joints, especially the wrists and the fingers; usually symmetrical)

- Psoriatic arthritis (often salmon-colored plaques over the knees, elbows, gluteal folds, and nail pitting)

- Associated fifth metatarsal fractures (Jones vs. styloid)

- Associated talar fractures (uncommon)

- Maisonneuve fracture (extends to the upper fibula)

- Bone tumors (rare)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree