Fig. 10.1

Anatomic diagram of an axial plane passing through the renal hilum. The figure shows the retroperitoneal, perirenal and pararenal (anterior and posterior) spaces, the Gerota (arrow) and Zuckerkandl (arrowhead) fasciae. A renal artery, K kidney, L liver, P pancreas, S spleen, V renal vein

The kidney is divided into eight 18 lobes. Each of them consists of the cortical mantle, approximately 1 cm wide, and the renal pyramid (Malpighi’s pyramid), whose apex (papilla) opens up into a minor calyx. The columns of Bertin are the extension of the renal cortical tissues which separate the pyramids. The number of minor calyces, around the base of the papilla, is equal or inferior to the pyramids of Malpighi, since two–three papillae may be merged together (in such a circumstance, the papilla represents the apex of a number of pyramids and it is termed renal crest). The major calyces (superior, middle and inferior), formed by the confluence of the minor ones, merge together in the pelvis. The morphology of the calyces and the pelvis has a high level of individual variability. The opposite options are dendritic (ramified) and ampullary shape (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2

Coronal anatomic diagram of the right kidney. The figure shows the cortex (C), the renal columns of Bertin (B) and the pyramids (P) with the minor calyces opening at the apex of the latter. We can see the superior, middle and inferior calyceal groups merging into the pelvis (star)

The renal vascularization is usually supplied by a vein and an artery, widely ramified in the renal sinus and forming two consecutive capillary circles: the first one, formed by a network of capillaries for the filtration, enters the structure of the nephron, and the second one, consisting of the vasa recta (straight arteries of kidney), with gas exchange functions, along with typical functions of capillary beds in general, is also responsible for the urine concentration mechanism.

10.1.2 Ureters

The ureter is a tube which propels urine from the pelvis to the urinary bladder, approximately 30 cm long, with a diameter of 5 mm. It lays in the retroperitoneal region, its course is medial oblique from top to bottom, and the openings into the urinary bladder is only a few centimetres far from the contralateral. It is divided into three segments, abdominal, pelvic and intramural segments (in the gallbladder wall), and it terminates into the ureteral meatus (Fig. 10.3). The anatomy of the second tract is obviously different in men and women. In women, it is strictly adjacent to the uterine artery and therefore vulnerable during surgery on the genital apparatus (risk of ligature of the ureter). The intramural segment, 1.5 cm long, is identical in both sexes: oblique along the urinary bladder wall, it crosses below and in the front the relevant layers, reaches the mucosa, and ends in a slit, the ostium ureteris, where a visible fold is present on the vesical lumen. The ureter has two physiological points of constriction (isthmuses): the first one after the origin, 7 cm far from the renal hilum, and the second one on the border between the abdomen and the lesser pelvis.

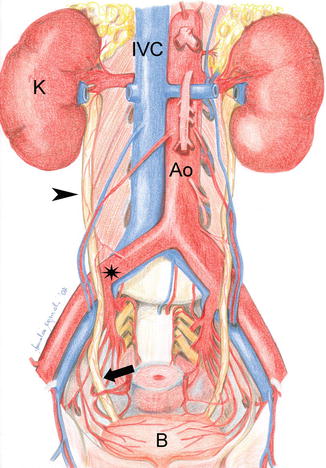

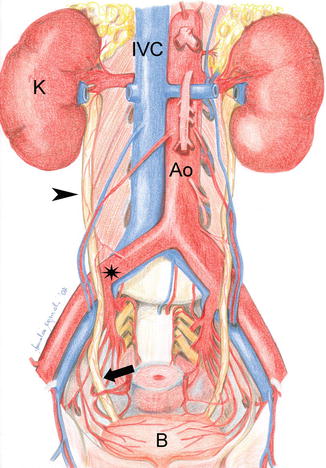

Fig. 10.3

Overall anatomy of the urinary system, coronal view. The figure shows the course of the ureters, abdominal part (arrowheads) and pelvic part (arrow), crossing the iliac vessels (star on the iliac artery). Ao aorta, B urinary bladder, IVC inferior vena cava, K kidney

10.1.3 Urinary Bladder (Vesica Urinaria)

The urinary bladder is an uneven and median muscular-mucous organ in the anterior part of the pelvic cavity, situated extraperitoneally. When full of urine, it is oval in shape, and we can distinguish the base (fundus), slightly flattened, and the vault. In the lumen of the bladder, we find the trigone, a triangular area with anterior apex, the urethral opening and posterior base, delimited by the urethral orifices (Fig. 10.4). They have a major oblique axis converging on the median line and characterised by a posterior fold which compresses the opening during the distension of the urinary bladder, acting as a valve. The ureteric folds, behind the trigone, are originated by the intramural oblique course of the ureters in the submucosa, delimiting the fundus of the bladder. In elderly men, it may be lower than the trigone of the bladder, especially if associated with prostatic hypertrophy. In such a condition, the urethral opening is not the most declive point of the bladder, and the evacuation is not complete.

Fig. 10.4

Anatomy of the female urinary bladder, coronal view. The figure shows the ureteric orifices (arrowheads) on the superior angles of the trigone (T) and the urethra (curved arrow)

The fundus of the bladder, in men, is adjacent to the prostate, the seminal vesicles and terminal tract of the deferent ducts, and the rectum is posterior to the bladder. In women, the uterus lays above the vault of the bladder.

The peritoneal serosa covers the vault of the bladder and, in men, bends on the anterior surface of the rectum forming the rectovesical space. In women, after covering the superior surface of the bladder, the serosa bends on the anterior surface of the uterine body. Between the two organs, there is therefore a peritoneal fissure enabling the raising of the uterus from the vault of the bladder. The fundus of the bladder is also adjacent to the uterine cervix, up to the vaginal fornix. Such structures separate the urinary bladder from the pouch of Douglas, or rectouterine pouch.

10.1.4 Urethra

In adult men, the urethra has an average length of 18–20 cm. Only the first tract is exclusively for urine (urinary urethra, corresponding to the whole length in women). Subsequently, starting from the seminal colliculus, or verumontanum, and, namely, from the opening of the ejaculatory ducts to the external meatus, it also allows the passage of the seminal fluid (common urethra). According to the adjacent organs, in men, the urethra is divided into three segments: prostatic portion, 3–3.5 cm long, with the seminal colliculus which is the terminal part of the ejaculatory ducts; membranous portion, really short (1–1.5 cm) in the urogenital diaphragm; and spongy or cavernous portion, 13–15 cm long, in the spongy body of the penis. It is divided into bulbar, penile and navicularis urethra (Fig. 10.5). The female urethra is 4–5 cm long and opens in the anterior part of the vestibule of the vagina. The lumen, narrowed towards the extremities, where it is 7 mm wide, is easily dilated allowing a surgeon to introduce instruments up to 2 cm in diameter (Fig. 10.6).

Fig. 10.5

Male pelvis anatomy, sagittal view; rectum (R), urinary bladder (B), prostate (star), prosthatic urethra, membranous (arrowhead) and cavernous (arrows) tracts are shown

Fig. 10.6

Anatomy of the female pelvis: rectum (R), uterus (U), urinary bladder (B), vesicovaginal (star) and rectovaginal septa (double star), urethra (arrowhead) and vagina (arrow)

10.2 Normal Imaging Anatomy

10.2.1 Conventional Radiology

Under normal conditions and in absence of meteorism, plain film radiography shows the shades of the kidney in frontal projection, immediately beside the psoas muscles. In lateral projection, the renal shadow overlaps the spinal column. On plain film, ureters are not visible while the urinary bladder, if full, appears as a slightly radiopaque rounded shadow (Fig. 10.7).

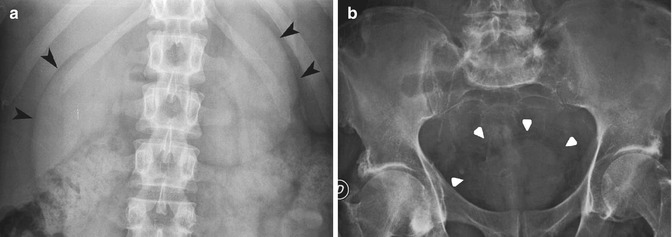

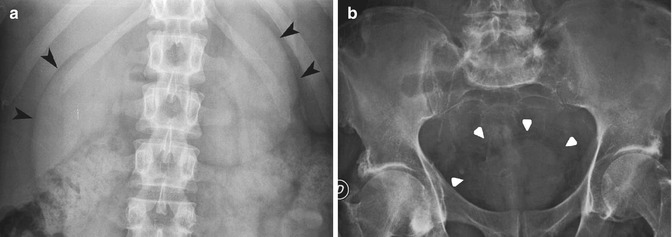

Fig. 10.7

Abdominal plain film. (a) Detail of the renal shadows (arrowheads). (b) Detail of the pelvic cavity and shadow of the urinary bladder (arrowheads)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree