James B. Spies

Uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) is now well established as an effective treatment for uterine fibroids, with substantial evidence of its efficacy. Since the first published small case series reported by Ravina et al.1 in 1995, there have been hundreds of publications on the procedure, including several randomized trials. The accumulated evidence led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists2 in 2008 to recognize UFE as a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy in women who have completed childbearing.

This chapter reviews the indications for UFE, the technical details of the procedure, periprocedural care, and anticipated outcomes, with the intent of summarizing this treatment option and its place in current fibroid management.

BACKGROUND

Leiomyomas are the most common tumor of the female reproductive tract, affecting a large proportion of women of reproductive age, with a cumulative incidence of 80% in African American women and nearly 70% in Caucasians by age 50 years in the United States.3 The prevalence is even higher if hysterectomy specimens are examined using serial thin uterine sections, with leiomyomas found in 77% of uteri in one study.4

Fibroids are a condition of women of reproductive age, typically arising in a patient’s 30s and regressing after menopause. The natural history of fibroids is typically progressive growth until menopause, with the greatest growth most likely in medium to large fibroids that are intramural.5 The growth rate is variable between patients and for individual fibroids within a single uterus.

Of those women with fibroids, a substantial proportion will develop symptoms during the course of their reproductive lives.6 The most common symptom is menorrhagia, which is often accompanied by cramping, pelvic pain, pressure, and increased urinary frequency. Less commonly, patients may have dyspareunia, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis. For many women, symptoms are of sufficient severity to warrant treatment.

TECHNICAL DETAILS

Patient Selection

To properly select patients for UFE, it is important that they be properly assessed with a gynecologic history and physical examination, including a pelvic examination by a medical provider experienced in gynecologic care. Often, this will be the patient’s gynecologist before referral for UFE evaluation. The diagnosis must be confirmed with imaging. The choice of imaging modality depends on available resources. Ultrasound certainly can confirm the diagnosis of fibroids and exclude other gynecologic pathology in most cases. However, the findings should be confirmed by personal review of the images rather than relying on the report alone. The quality of ultrasound examinations is very variable, and very poor quality or limited examinations should be repeated to ensure that other significant gynecologic pathology is not present.

Ideally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be the modality of choice for imaging fibroids and the uterus. It provides better spatial resolution and anatomic detail of the architecture of the uterus than ultrasound, and it also provides excellent assessment of adnexal structures. Some uterine conditions, such as adenomyosis, are much more reliably identified with MRI, and in one study, the management of patients was altered based on MRI findings in 22% of cases.7 Based on the MRI findings, UFE was not performed in 19% of women in whom the procedure was initially planned.

There are no clearly established criteria for who should or should not be treated with embolization. The evidence to date has not been definitive in establishing selection criteria. Some exclusion criteria have been suggested based primarily on a concern that some specific subtypes of fibroids or patients with certain clinical conditions might not do as well.8 The uterine-specific factors include uteri greater than 20 to 24 weeks size (potentially poorer outcomes), submucosal fibroids greater than 10 cm (due to potential increased risk of fibroid expulsion and infection), and pedunculated fibroids (either submucosal or serosal) that have an attachment to the uterine wall less than 50% the diameter of the fibroid (due to potential for detachment). Unfortunately, there is little evidence to support any of these suppositions, at least to the extent that the evidence makes these “contraindications.” For example, although there is some evidence that very large uteri may not have as much shrinkage as smaller uteri and patient satisfaction may trend lower,9 there are other studies suggesting this is not the case.10 Similarly, there is little evidence that narrow-based pedunculated fibroids are unsafe to treat.11,12

Other nonuterine factors that have been considered contraindications include large hydrosalpinx (due to perceived increased risk of infection), prior pelvic surgery, or procedure that might alter pelvic arterial anatomy, such as salpingo-oophorectomy or surgery for ectopic pregnancy or pelvic radiation. There is essentially no evidence to support these views.

Thus, there are few absolute contraindications and few proven relative contraindications. Clearly, current pregnancy or known or suspected uterine or adnexal malignancy are contraindications. Most anatomic limitations related to fibroids themselves are really in the context of considering the other treatment options for the patient. Large intracavitary fibroids may be more prone to expulsion, and in some cases, other treatments such as myomectomy or hysterectomy may be preferred. Similarly, a small pedunculated serosal fibroid in a multifibroid uterus may be best treated by UFE, whereas a large pedunculated single serosal fibroid might be better approached surgically with myomectomy.

Further, the question of future fertility must always be considered. Although the fertility outcomes are reviewed later in this chapter, the question of whether the patient is interested in future childbearing must be answered. The limited data available from randomized trials currently suggest that myomectomy should be the first consideration in a patient who would like to become pregnant in the subsequent 2 years.

When evaluating patients for UFE, the anatomy of the uterus, the presence or absence of adnexal abnormalities, the patient’s age, her interest in pregnancy, and her willingness to consider hysterectomy or other surgical alternatives all should be considered before making a recommendation for the patient. UFE is suitable for most patients with symptomatic fibroids, but so are other fibroid treatments. The patient should understand the range of the options for her in order for her to make an informed choice.

Technique

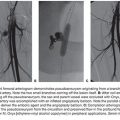

UFE is an angiographic procedure usually performed via femoral arterial access. Most practitioners use unilateral femoral access, usually on the right side. There is an alternate method, that of bilateral femoral access, which has been used by some groups. Because each UFE usually requires embolization of both uterine arteries, bilateral approach allows for simultaneous embolization. This results in shorter fluoroscopy times and shorter procedure times.13

Regardless of whether unilateral or bilateral access is used, UFE requires selective catheterization of the uterine arteries before embolization. There is some controversy regarding placement of the catheter tip within the vessel. Early in the development of UFE, a case report was published on a patient who experienced sexual dysfunction after UFE, and the authors speculated it could be from occlusion of the cervical vaginal branch of the uterine artery.14 This lead to the belief that embolization should only be done with the catheter tip distal to that branch. This can be difficult as it often arises from the mid transverse portion of the uterine artery and is distal to multiple looping segments of the vessel. Even with the use of a microcatheter, placement of the catheter tip at that level can be very difficult. This degree of manipulation of the catheter can also cause significant spasm in the vessel. Because successful embolization of the fibroids depends on the free flow of the embolic material to the fibroid vessels, it is important to avoid spasm that might impede that flow. Thus, our approach is to place the catheter tip distal to that branch if feasible without causing spasm, but if not, then more proximal position would be acceptable.

Spasm both limits the flow to the fibroids but can also lead to a false end point, with the appearance that there has been adequate reduction in flow when in fact a part of the apparent reduction in flow is due to flow restriction from spasm. One means of trying to avoid or relieve spasm is the use of a microcatheter. Some interventionalists use them routinely for just that reason, whereas others use them selectively. Use of a microcatheter should be the first consideration in relieving spasm. Antispasm medications, such as nitroglycerin, may also be used to help relieve spasm.

Once the catheter(s) is (are) in appropriate position, most interventionalists will perform a preembolization arteriogram to verify anatomy, assess for communications with the ovarian arteries, and ensure there are no abnormal arteriovenous communications before embolization. There is at least one reported case of misembolization of embolic material due to a uterine arteriovenous fistula, with embolic material passing through a patent foramen ovale into the heart, brain, and other organs.15

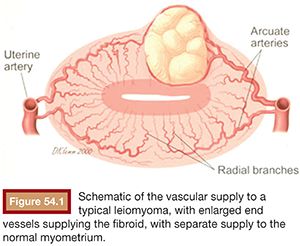

Embolic material is injected in small aliquots, with the flow within the uterine arteries carrying the embolic to the fibroid vessels. The vessels feeding fibroids are very large compared to normal myometrial branches (Fig. 54.1). As a result, the flow to them is greatest initially. There is therefore preferential flow to the fibroids. Fibroids are supplied by a limited number of end vessels, and if these are occluded, collaterals cannot reperfuse the fibroid. Because fibroids are very sensitive to ischemia, the occlusion of the feeding vessels typically results in the complete or near complete infarction of the fibroid without injury to adjacent normal myometrium (Fig. 54.2). The extent of fibroid occlusion can vary depending on the embolic material chosen and the end point of embolization. These two topics are discussed further in the following sections.

Although most patients will have uterine and fibroid supply from both uterine arteries, there are some variations. First, occasionally there is only one or perhaps two fibroids that are supplied by one vessel only, with the opposite uterine artery normal. These may be treated by unilateral embolization if certain conditions can be met. First, MRI should be used to clearly define the number and location of the fibroids and to confirm that they are only on one side of the uterus. Unilateral embolization of major fibroids and nontreatment of smaller fibroids on the opposite side will only hasten the recurrence of fibroids and should be avoided. With unilateral fibroids, angiography at the time of embolization must confirm supply to the fibroids from the one uterine artery only. The uterine artery that is to be considered for nonembolization must be normal, perfusing normal myometrium only. If these criteria are met, there is evidence that fibroid infarction rates will match those of bilateral embolization, and it is likely the patient will have diminished pain after embolization when compared to bilateral UFE.16,17

There are also variations of the uterine arteries or additional supply to the uterus or fibroids from other vessels, most commonly the ovarian arteries. Several studies have evaluated the frequency of ovarian artery supply to the uterus and it occurs in approximately 5% of cases.18–20 Most interventionalists will perform an aortogram after embolization if ovarian supply from the uterus is suspected. Pelage et al.21 recommended performing an aortogram in those cases in which there is a large uterus, a large fundal fibroid, prior myomectomy, or tubal surgery; a study should also be done in cases in which one uterine artery is diminutive or absent.

Currently, most experts recommend that if ovarian artery embolization is to be performed as an adjunct to UFE, a microcatheter should be used for selective catheterization of the vessel and that the tip of the microcatheter be advanced about a third of the distance from the origin to the level of the ovary. Embolization is typically performed with particulate embolics, and usually, only a small amount of embolic is needed, with an end point of near stasis regardless of embolic. In most cases of ovarian embolization, only one ovarian artery requires embolization. Although data are not extensive, it does not appear that embolization of the ovarian arteries increases the risk of ovarian failure after embolization.22–24 Rarely, other sources of supply, such as the round ligament artery25 or the inferior mesenteric artery,26 can provide the uterus or fibroids and should be considered when neither the uterine or the ovarian arteries appear to provide all the vascular supply to the fibroids.

Embolic Material

There are several embolic materials currently available for embolization and also a considerable amount of literature regarding the relative effectiveness of these different products.

There are three embolic materials currently cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for UFE. These are trisacryl gelatin microspheres (TAGM, Embosphere Microspheres; Merit Medical Systems, Inc., South Jordan, Utah), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (Contour; Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, Massachusetts), and spherical polyvinyl alcohol (sPVA, Contour SE; Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, Massachusetts). There are additional materials that are cleared for use for hypervascularized tumors and that are regularly used for fibroid embolization. These are acrylamido PVA microspheres (Bead Block; Biocompatibles, Inc., Oxford, Connecticut), Polyzene-F–coated PVA hydrogel spheres (Embozene Microspheres; CeloNova BioSciences, Inc., San Antonio, Texas), and PVA particles (Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, Indiana). In addition, gelatin sponge is used in some settings, although it does not have FDA clearance for use as an embolic agent.

There have been several studies comparing the outcomes of embolization from different embolics. Based on the outcomes from some long-term studies, it has become clear that the best measure of an embolic’s efficacy for UFE is the extent to which the fibroids are infarcted.27 This has been measured by estimating the fibroid infarction rate, usually the estimated percentage of the visible fibroid tissue no longer perfused on a contrast-enhanced MRI.28

The first randomized comparative study of embolics for UFE was by Spies et al.,29 in which the outcomes of UFE using TAGM and PVA particles were compared. Surprisingly, there were few differences between the materials. Before that study, it was widely believed that the use of TAGM caused less postprocedural pain than PVA, but no difference was found. The fibroid infarction rates were nearly identical, with 77% of TAGM and 76% of PVA patients with complete fibroid infarction. This study set the benchmark by which other embolics would be subsequently be compared.

The same group initiated a second study comparing sPVA to Embospheres for UFE and surprisingly did find a significant difference between the two materials.30 There was a large difference in fibroid infarction rate, with sPVA having a mean residual perfused fibroid volume of 44% versus 9.6% for TAGM. The TAGM group also noted a greater improvement in quality of life scores at 3 months after treatment. Siskin et al.31 published a similar comparative study and had similar findings: treatment failure in 29.6% of the sPVA group and 3.8% for TAGM, with less fibroid infarction in the sPVA group. Additional studies have confirmed that for UFE, spherical PVA is not as effective as conventional PVA and TAGM for this procedure.

A single randomized trial has compared acrylamido PVA microspheres to TAGM. No difference in fibroid infarction rates was noted, although there was a better quality of life outcome for TAGM.32 Unfortunately, there were only 44 patients in this study, a small number to compare the embolic efficacy. There have been other nonrandomized trials that have found poorer outcomes with acrylamido PVA, and at this time, the question remains unsettled.

There are case series supporting the efficacy of Polyzene-F–coated PVA hydrogel spheres (Embozene),33,34 with preliminary evidence suggesting excellent clinical outcomes and high rates of fibroid infarction. There are no comparative studies published to date with the product, although a randomized trial is ongoing currently.

There is relatively little published experience on the use of gelatin sponge for UFE in Western countries, but it has been the standard used in Japan for many years. Katsumori35–37 has reported extensively on both the short- and long-term outcomes using this material, finding very similar short-, mid-, and long-term outcomes. Whereas in the West gelatin sponge is commonly used as a slurry or as large pledgets, in Japan, it is cut into very small particles of between 500 and 1,000 µm in size. It is not known whether this preparation is critical in obtaining good results.

End Points of Embolization

There has been much discussion over the years regarding the extent to which the uterine arteries need to be occluded to result in fibroid ischemia sufficient to infarct the fibroids. These discussions have been hampered by the lack of tools to objectively measure the end point. Most articles reporting results have used a descriptive end point that can be subject to variation in interpretation.

Initially, UFE was performed with PVA, with either a gelatin sponge plug or a coil used at the end of the embolization to completely occlude the uterine artery, leaving just a stump of a vessel.38,39 Although the initial results suggested this was successful in causing fibroid shrinkage and presumably fibroid infarction, it also resulted in very significant ischemic pain immediately after the procedure. This technique has been largely abandoned.

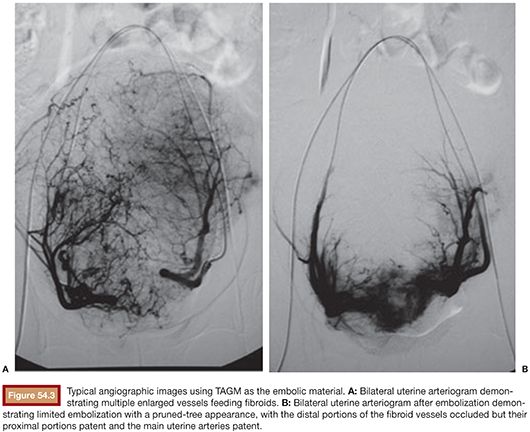

When TAGM was first tested in the United States, a descriptive end point was created, with complete occlusion of the fibroid flow but with remaining slow flow in the uterine arteries.40 This has subsequently been described as the pruned-tree appearance, with complete distal occlusion of the uterine artery branches to the fibroids, but the main trunk of the uterine artery still patent with sluggish flow (Fig. 54.3). This has become the standard end point of embolization, and complete occlusion of the vessel by TAGM results in more severe ischemia and therefore should be avoided as TAGM packs tightly in vessels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree