PART IX Protheses

CASE 130

Joint Arthroplasty

Peter L. Munk, Anthony G. Ryan, and Laurel O. Marchinkow

Clinical Presentation

A 73-year-old woman presents with persistent pain in her left hip 18 months after total hip arthroplasty.

Figure 130A

Radiologic Findings

Left anterior oblique (LAO) radiograph (Fig. 130A) of the pelvis shows a lucent rim around the acetabular component at the cement–bone interface.

Diagnosis

Loosened acetabular component secondary to infection with an indolent organism.

Differential Diagnosis

- Sterile loosening

- Histiocytic response

Discussion

Etiology

The vast majority of arthroplasties are performed on the hip for chronic degenerative joint disease. Arthroplasty for smaller joints is more commonly performed to treat inflammatory arthropathies unresponsive to the best medical management and when function is severely limited.

Imaging Findings

RADIOGRAPHY

Hip

The most common arthroplasties are of the hip, and it is with these that the greatest experience has been accrued. A wide variety of different types of hip arthroplasty devices have been developed over the past several decades, and these are in constant evolution, with new types being introduced every year.

Metal, plastic, and ceramic are used in varying combinations and designs. The exact appearance and orientation of the arthroplasties varies from one design to the next; therefore, only certain broad generalizations can be made.

The acetabular component is normally anteverted, although some varieties are held in neutral position. The degree of anteversion requires measurement from a true lateral film. The femoral component is normally seated centrally within the medullary cavity of the proximal femur, although slight valgus orientation is frequently noted and considered acceptable.

Both acetabular and femoral components may be cemented or uncemented. Occasionally, one component may be cemented and the other uncemented. Uncemented components normally have a slightly corrugated surface due to the presence of numerous tiny beads adherent to the surface to promote bone ingrowth for long-term fixation.

A small amount of radiolucency between the bone and cement is a common finding, typically measuring 1 to 2 mm in width. In the long term, a thin radiodense line or neocortex between the cement and inner cortex may form, which should not be misinterpreted as loosening.

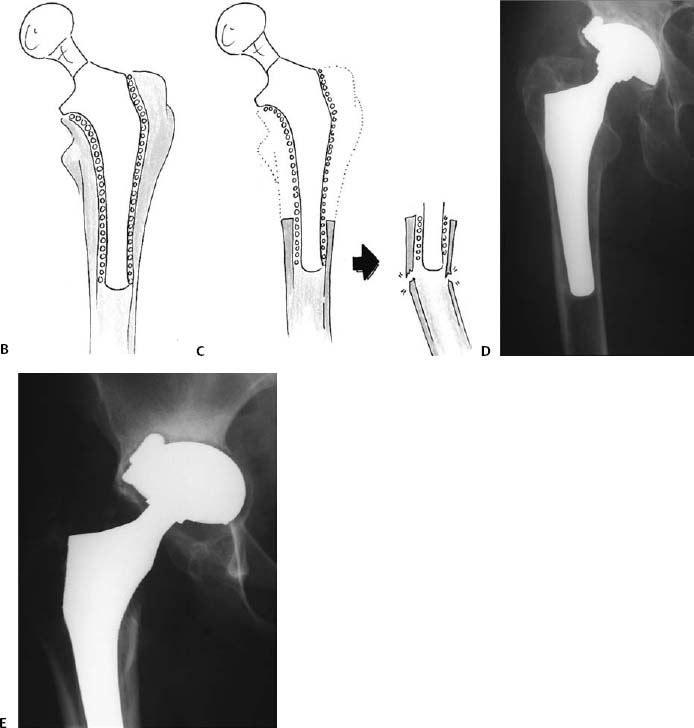

A small amount of resorption of bone at the medial calcar region, where the femoral stem rests against the medial cortex, is also common. This is due to a relatively reduced stress load on the cortex at this site, referred to as stress shielding (Figs. 130B–130E).

Knee

Knee arthroplasty is also frequently performed. The most common type of arthroplasty is a total knee arthroplasty, where both medial and lateral compartments of the knee are resurfaced. This may or may not include resurfacing of the patellar surface. Occasionally, a single compartment (medial or lateral) may be resurfaced if little disease is present in the opposite compartment.

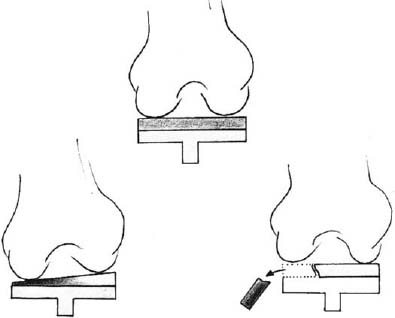

Typically, both the femoral and tibial components have a peg projecting into the medullary space of the respective bone. Arthroplasties that have undergone revision, that is, second or third arthroplasties, typically have much longer stems to provide stability.

In most instances, a plastic tray is present on the tibial component that is of variable thickness, depending on the amount of bone that must be resected (Fig. 130F). A thicker plastic component helps maintain leg length, especially where there has been bone loss.

Shoulder

In the upper extremity, the most common type of arthroplasty is shoulder arthroplasty. This may consist of simply a humeral component, particularly in the case of complex proximal humeral fractures, or a total joint arthroplasty, where a resurfacing button is placed in the glenoid fossa of the scapula (more commonly used in patients with arthritis).

Because stability of the shoulder joint is provided largely by ligaments and tendons, the structures must be carefully assessed prior to performing an arthroplasty. The principal indication for shoulder arthroplasty is improvement of patient pain rather than improvement of joint function.

Commonly after arthroplasty, slight cranial displacement of the humeral component in relation to the scapula is noted, partly as a result of loss of bone in the upper scapula due to arthritic change. Marked cranial displacement usually reflects the presence of rotator cuff rupture.

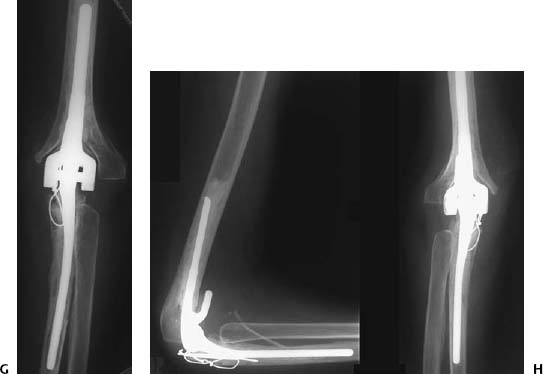

Other joints

Less common arthroplasties are noted elsewhere in the upper extremity, such as the elbow (Figs. 130G,130H), distal ulna, wrist, and carpal bones (Figs. 130I–130M), as well as the metacarpophalangeal joints (Fig. 130N).

The most common indication for this type of arthroplasty is arthritis, particularly rheumatoid arthritis or, in the case of carpal bones, trauma or avascular necrosis. In the case of many smaller bones or joints, the arthroplasty may employ a plastic or metal spacer or hinge rather than a complex joint device (Figs. 130J–130L).

Arthroplasties in the lower extremity below the knee are infrequently performed, although a few centers do perform ankle joint replacement (Figs. 130O,130P). These are technically challenging procedures with an unpredictable clinical outcome.

Figures 130G,130H 130G

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree