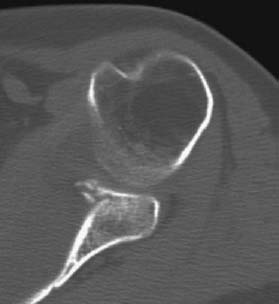

CASE 96 Hema N. Choudur, Anthony G. Ryan, Peter L. Munk An elderly inpatient was sent for a chest radiograph after an awkward fall in the hospital. Figure 96A Figure 96B The chest radiograph (Fig. 96A), initially reported as showing no bone or joint abnormality, was reviewed, with the additional information that the patient complained of ongoing left shoulder pain. The radiograph shows the humeral head to be in a subcoracoid location. Further shoulder views (anteroposterior (AP), Fig. 96B; trans-scapular, Fig. 96C) confirm the subcoracoid, anterior location of the humeral head with respect to the glenoid. Although both the postreduction AP (Fig. 96D) and axillary (Fig. 96E) views confirm relocation, the axillary view also demonstrates cortical discontinuity and a subchondral lucent line on the anterior aspect of the glenoid rim. Transaxial CT images (Figs. 96F–96H, from superior to inferior) demonstrate a minimally displaced fracture with a degree of fragmentation and a subchondral fracture line. Anterior dislocation of the left shoulder with a Bankart lesion. None. Figure 96D Figure 96E Figure 96F Figure 96G Figure 96H The shoulder accounts for 50% of all joint dislocations. Traumatic anterior dislocations are the most common (90 to 98%), most of which are subcoracoid in location. Subglenoid, subclavicular, and, very rarely, intrathoracic dislocations may occur. Whereas labral tears following traumatic dislocation are more common in individuals younger than 40 years, rotator cuff tears are more frequent in older individuals. The vast majority of shoulder dislocations are traumatic, with several predisposing factors identified: a small or flat glenoid fossa, excessive anteversion or retroversion of the glenoid (a dysplastic glenoid is present in 13% of patients), weak rotator cuff muscles, neuromuscular disorders, or a redundant capsule result in a decrease in humeroglenoid stability. Also, laxity of ligaments as seen in Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome can result in nontraumatic dislocations, for example, after a sneeze or minimal motion. Anterior dislocation is most commonly caused by forceful abduction and/or external rotation alone (in ~30% of cases); however, a direct blow to the posterior humerus, forced elevation and external rotation, or a fall onto an outstretched hand may also be causative. Posterior glenohumeral dislocations are uncommon and account for ~2 to 10% of all shoulder dislocations. They can occur following a fall with the arm in adduction, internal rotation, and flexion, or following electroshock therapy and seizures. A direct blow to the anterior shoulder uncommonly can result in a posterior dislocation. Inferior dislocations are rare and result from a hyperabduction force. Diagnosing inferior dislocations is crucial because of the high incidence of associated complications. Superior dislocations are extremely rare and result from an extreme cephalad force to the adducted arm. Acromioclavicular injuries and fractures of the acromion, clavicle, and tuberosities are common attendants of such injuries.

Shoulder Dislocation

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree