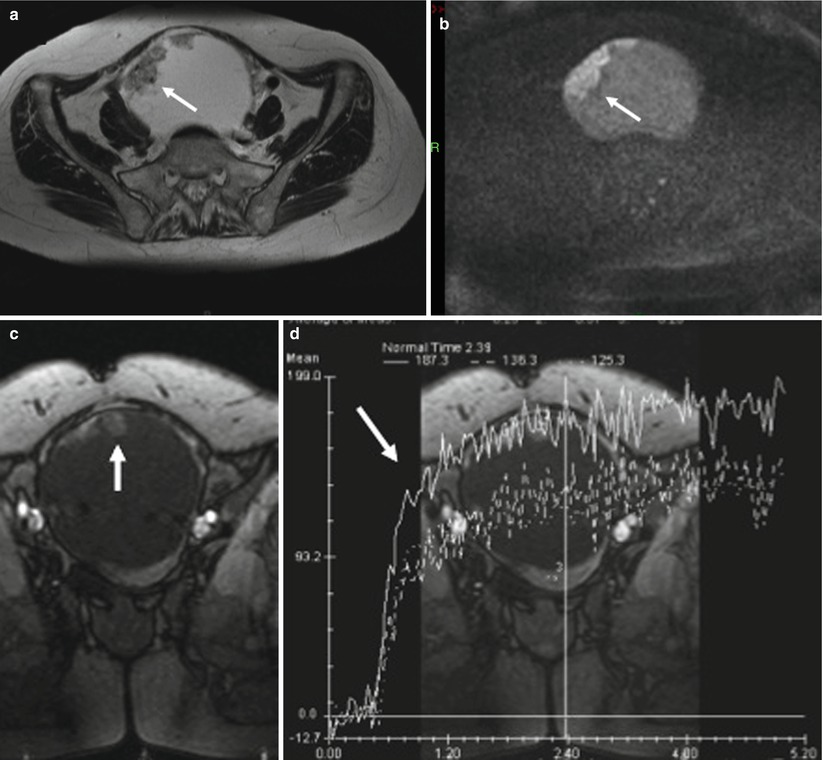

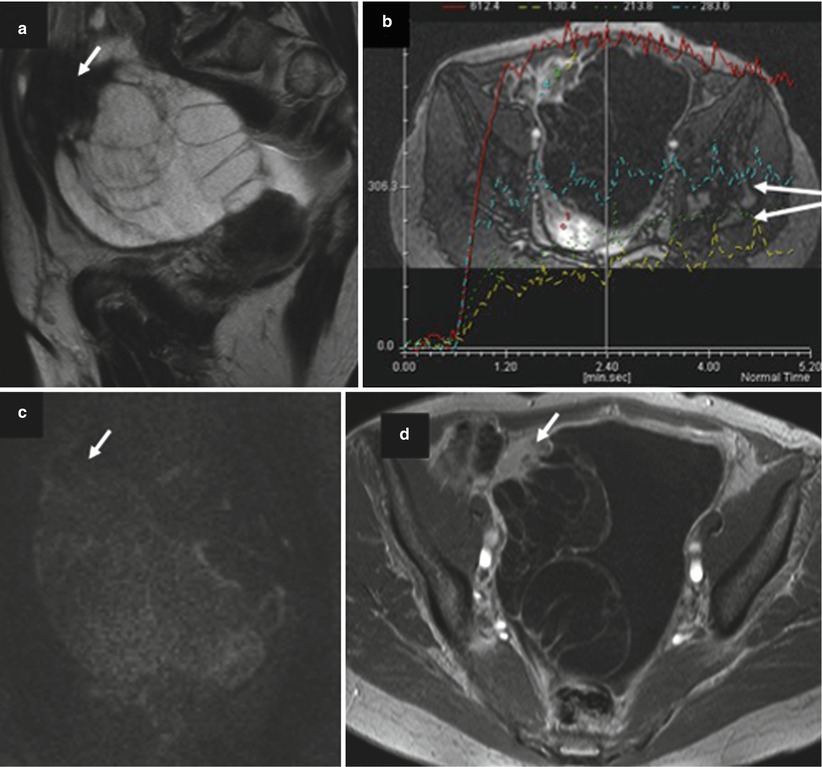

Fig. 1

Images in a 35-year-old woman with bilateral low-grade serous carcinoma developed on serous borderline tumors, Figo IC (large white arrows). (a) Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows bilateral complex adnexal tumors with right cystic and solid irregular components and left endocystic nodule with intermediate signal intensity (arrows), (b) transverse DW MR image obtained at b = 1,000 s/mm2 shows the presence of high signal intensity in solid components (arrows), (c) transverse T1-weighted MR image obtained without fat suppression, (d) transverse fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows enhancement in the solid components of both tumors (arrows). Note that the combination of intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI sequence and high signal intensity on DWI of solid components was significant for distinguishing invasive from noninvasive ovarian tumors

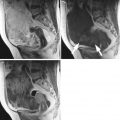

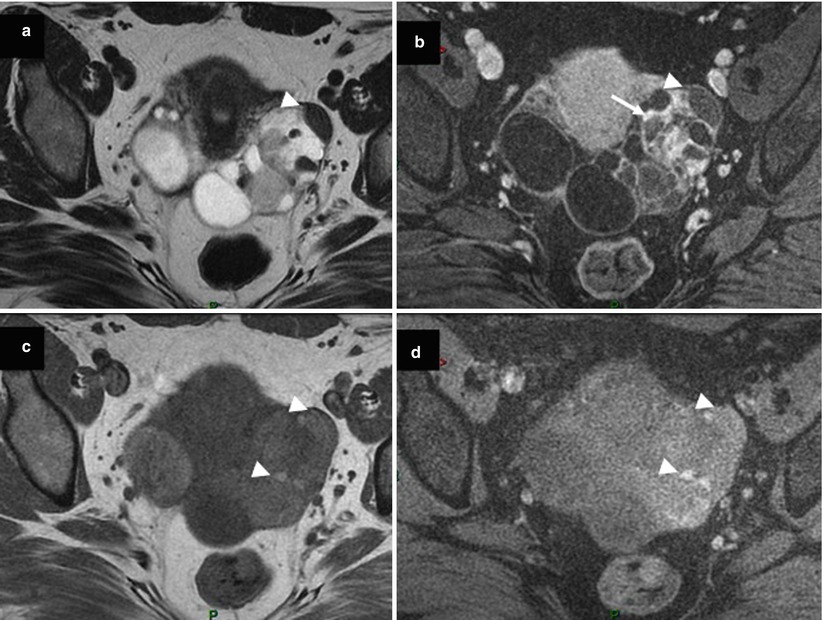

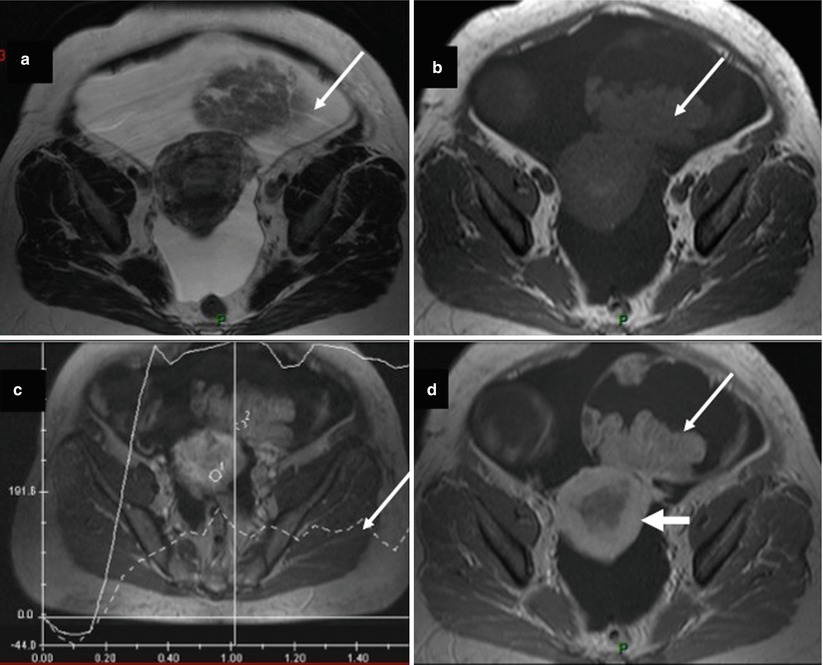

Fig. 2

Images in a 70-year-old woman with left low-grade serous carcinoma, Figo IC. (a) Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows multiple endocystic vegetations displaying intermediate signal intensity (arrow), (b) transverse DW MR image obtained at b = 1,000 s/mm2 shows the presence of high signal intensity in endocystic vegetations (arrow), (c) coronal T1-weighted DCE MR image obtained without fat suppression shows uptake of contrast medium in vegetations, (d) coronal T1-weighted DCE MR image obtained without fat suppression shows a curve type 3 in endocystic vegetations (arrow). Note that the combination of vegetations with intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI sequence, high signal intensity on DWI, and curve type 3 was pathognomonic of serous cystadenocarcinoma

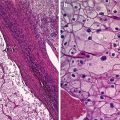

Several studies underlined the limitation of all these criteria (i.e., solid mass and vegetations) to distinguish invasive stage IA–B from borderline or benign ovarian tumors [33]. Different comments could be provided according to these potential limitations. Firstly, with the exception of benign cystadenofibromas (and Brenner tumors), almost all benign serous ovarian tumors are predominantly cystic or cystic papillary without solid area [25]. In addition, the solid component of cystadenofibroma (and Brenner tumor) is almost always hypointense on T2-weighted MR imaging, this criterion being a well-known finding predictive of benignity [34, 35]. Secondly, a lot of MR studies have shown vegetations in 38–48 % and 61–67 % of invasive and borderline ovarian tumors (BOT), respectively [3, 12]. In a recent study using multivariate analysis, Bazot et al. suggested that the presence of vegetations displaying intermediate signal on T2-weighted MRI and curve type 2 on DCE MRI sequence was highly suggestive of serous BOT (Fig. 3) [36]. A particular form of serous BOT (i.e., serous surface papillary borderline ovarian tumors) (SSPBT) was recently underlined [36–38]. Serous surface papillary tumor of the ovary displays a surface proliferative pattern and shows papillary excrescences on its surface [1]. SSPBT is therefore usually an entirely solid mass that generally lacks areas of necrosis or hemorrhage [25]. During differential diagnosis, ovarian tumors with a rich solid component are considered malignant based on cross-sectional imaging findings [12, 25]. SSPBT may therefore be diagnosed as a highly malignant ovarian tumor by MRI [25]. However, Tanaka et al. recently reported six cases showing a papillary architecture and internal branching (PA&IB) pattern with frond-like projections on T2WI correlated at histopathology with epithelial multilayering, forming papillae with a thick fibrous stalk (Fig. 4) [25]. This PA&IB pattern appears as a characteristic MR imaging feature of SSPBT that cannot be obtained using CT alone [25]. Another striking finding is visualization of normal ovaries in the mass or masses (if bilateral), most clearly on T2-weighted MR images [37]. In contrast, serous ovarian carcinomas with exophytic vegetations have always associated solid masses.

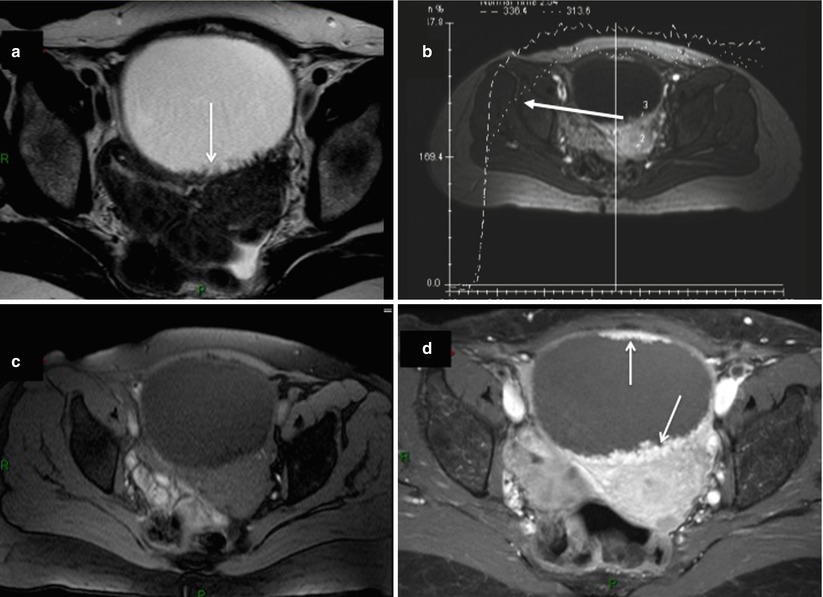

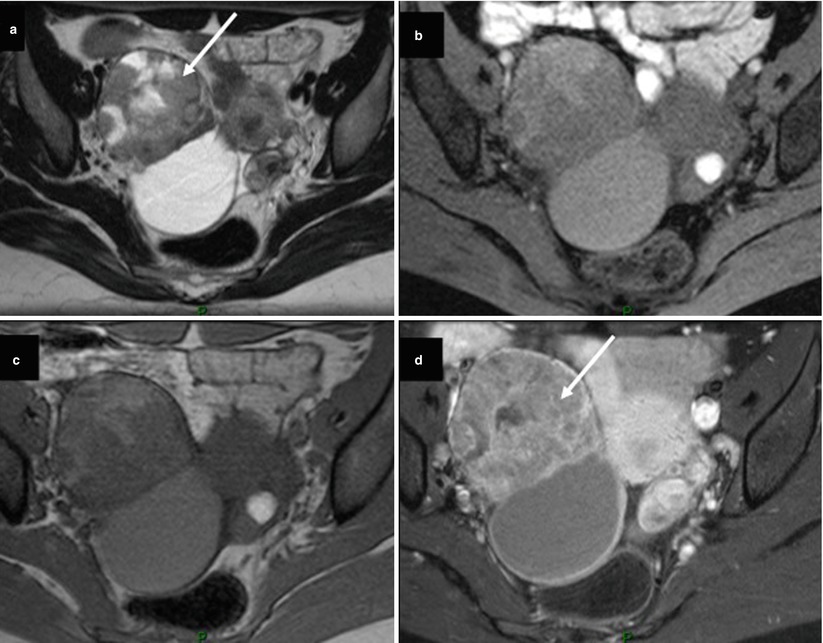

Fig. 3

Images in a 63-year-old woman with serous borderline ovarian tumor. (a) Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows left unilocular cystic tumor containing multiple irregular endocystic vegetations with intermediate signal intensity (arrows), (b) transverse dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MR image shows curve type 2 within endocystic vegetations, (c) transverse T1-weighted MR image obtained without fat suppression, (d) transverse fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows enhancement in anterior and posterior endocystic vegetations (arrows). Note that the combination of the presence of vegetations displaying intermediate signal on T2-weighted MRI without associated solid masses and curve type 2 on DCE MRI sequence was highly suggestive of serous BOT

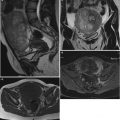

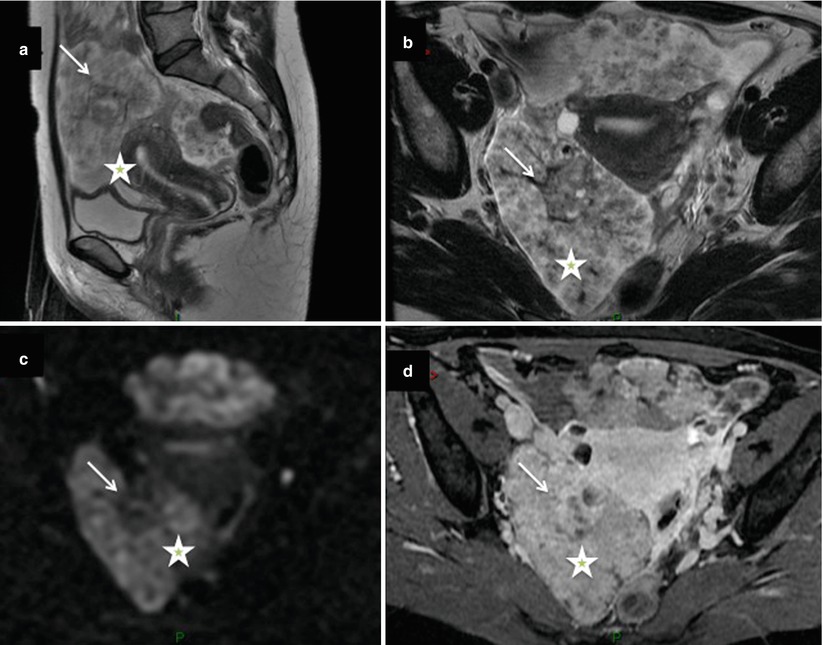

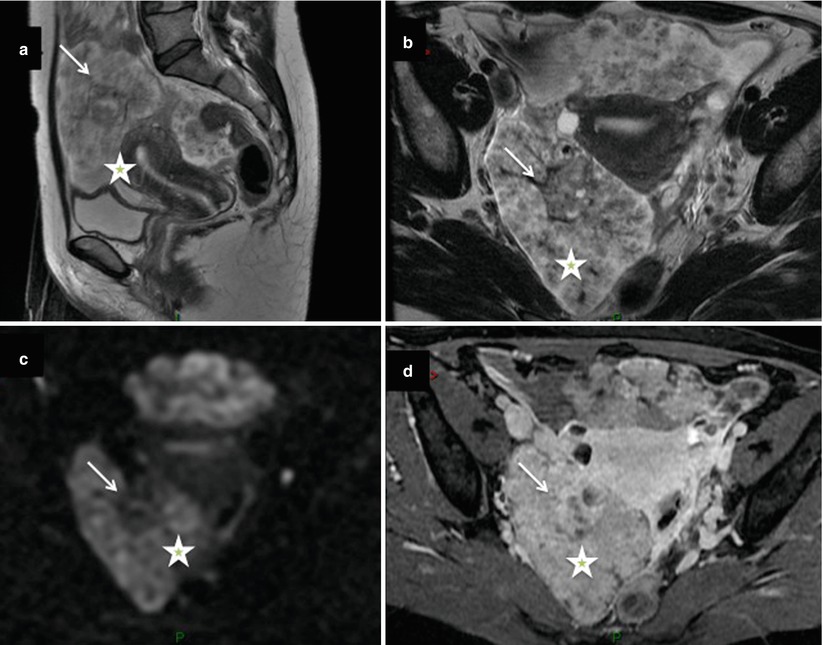

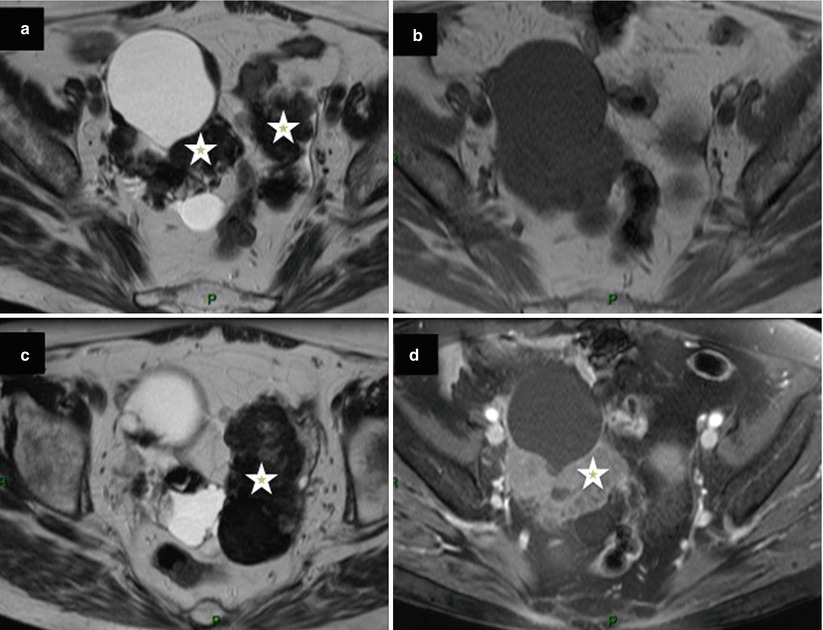

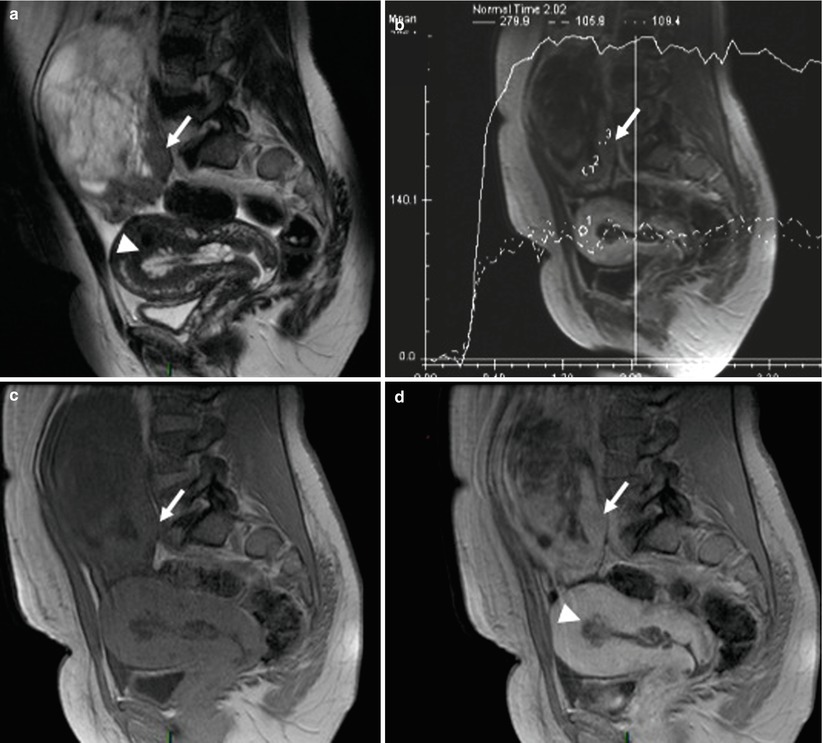

Fig. 4

Images in a 42-year-old woman with bilateral serous surface papillary borderline tumors. (a) Sagittal and (b) transverse T2-weighted MR images show bilateral, entirely solid ovarian tumors showing a papillary architecture and internal branching pattern with frond-like projections with intermediate signal intensity (asterisks), (c) transverse DW MR image obtained at b = 1,000 s/mm2 shows the presence of high signal intensity in solid components (arrows), (d) transverse fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows enhancement in the exophytic vegetations of both tumors (asterisk). Note the visualization of normal ovary in the right mass, most clearly on T2-weighted MR images (arrows)

Few studies have specifically evaluated the value of CT for the differentiation of ovarian cancer subtypes [39, 40]. Calcification is the most frequent finding suggestive of serous ovarian carcinoma. However, this criterion is not specific, being present in many benign ovarian tumors such as mature teratoma, fibroma, or Brenner tumor. The presence of calcifications (psammoma bodies) is variable in ovarian carcinoma histopathological studies (14.3–30 %) [1, 41]. CT compared to histology has a low sensitivity to detect calcification within ovarian tumors (4.7–8 %) but provides an overview of the abdominal and pelvic cavity. In this setting, Burkill et al. reported that calcifications tend to occur most commonly in serous cystadenocarcinomas of lower grade [42].

Mucinous Subtype

More than 80 % of mucinous cystadenocarcinomas tend to remain confined to the ovary and pelvis (early stage) at the time of diagnosis [1]. Mucinous malignant ovarian tumors are unilateral, generally cystic, and often very large and tend to be multiloculated [43]. They often have variable signal intensity in the loculi, owing to proteinaceous or mucinous contents and hemorrhage [27]. It must be reemphasized that mucinous tumors, unlike serous tumors, often vary in their degree of differentiation from one area to another at histopathological examination [1]. Hence, benign, borderline, and invasive patterns may coexist within the same specimen [1]. In our experience, the presence of solid mass with intermediate intensity on T2-weighted MR sequence in a large multiloculated lesion is the best predictive criterion of malignancy among mucinous ovarian tumors. MR imaging is the best technique to depict such solid tissue. The presence of high signal intensity within solid mass on DWI is low predictive of malignancy [14]. However, the presence of curve type 2 or 3 on DCE MR sequence in solid mass reinforces the diagnosis of malignancy (Fig. 5). The combination of all these findings is valuable, allowing distinction of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma from other large multiloculated cystic ovarian tumors. In this setting, different epithelial and non-epithelial ovarian tumors should be ruled out to avoid misinterpretations [12]. The most frequent ovarian lesions that may resemble to ovarian cystadenocarcinoma are cystadenofibroma, struma ovarii, granulosa tumors, ovarian metastases, and collision tumors. Some important features are important to recall allowing potential differential diagnosis.

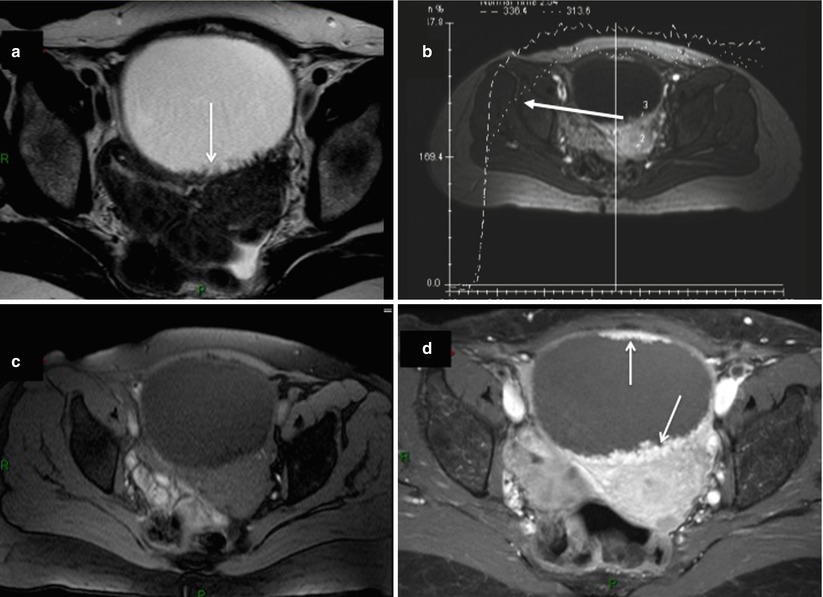

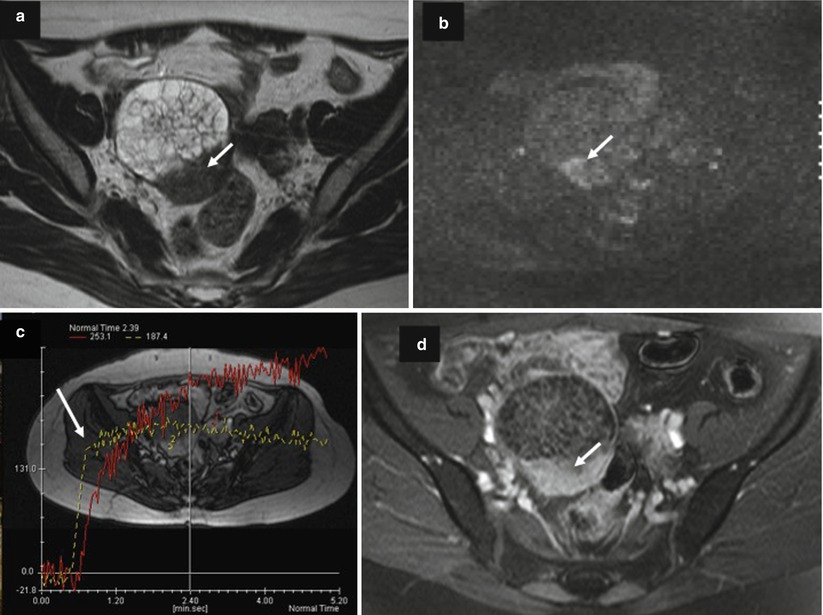

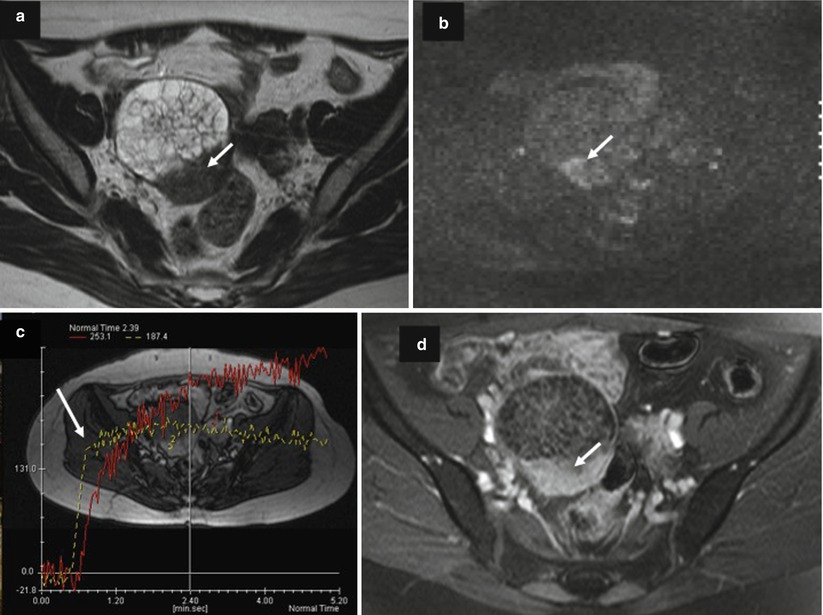

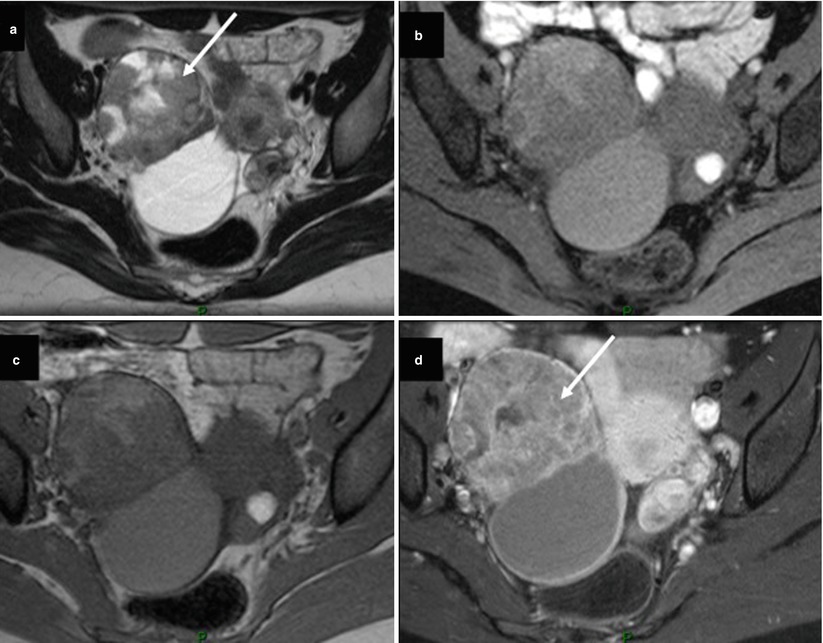

Fig. 5

Images in a 64-year-old woman with mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. (a) Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a multiloculated cystic ovarian tumor with multiple irregular septa and posterior solid mass with heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity (arrow), (b) transverse DW MR image obtained at b = 1,000 s/mm2 shows the presence of high signal intensity in solid mass (arrow), (c) transversal T1-weighted DCE MR image obtained without fat suppression shows a curve type 3 in solid mass related to carcinomatous component (arrow), (d) transversal T1-weighted postcontrast MR image shows enhancement of irregular septa and solid mass (arrow)

Benign cystadenofibroma may present as a multiloculated cystic mass with irregular thickened septa with heterogeneous signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted MR images or with a regular solid mass exhibiting low signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images with slight delayed uptake of contrast medium on postcontrast T1-weighted images. In addition to low signal intensity on T2-weighted, the presence of a curve type 1 on DCE MR sequence within solid tissue is a valuable tool for the diagnosis of cystadenofibroma (Fig. 6).

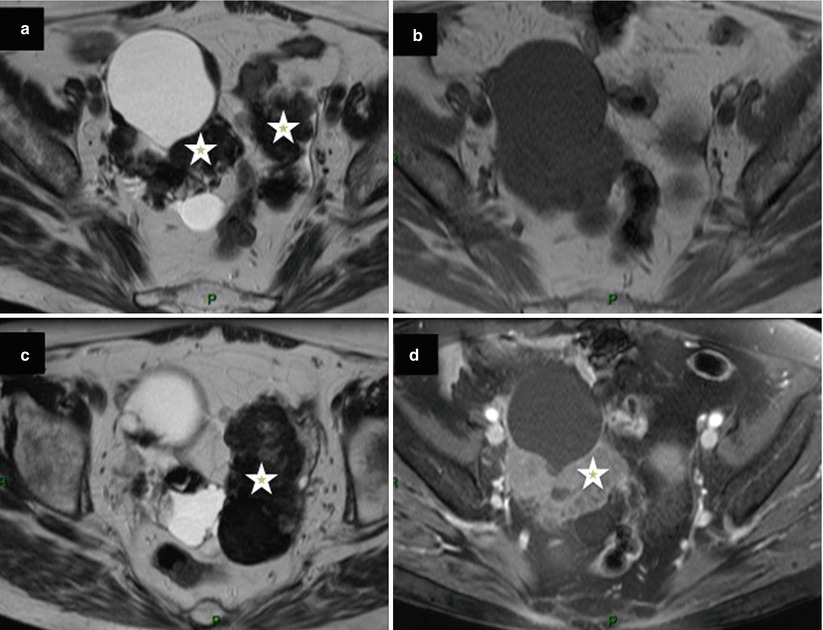

Fig. 6

Images in a 67-year-old woman with bilateral cystadenofibroma. (a, c) Transverse T2-weighted MR images show bilateral mixed ovarian tumors with cystic components and solid regular components with low signal intensity (asterisk), (b) transverse T1-weighted MR image obtained without fat suppression, (d) transverse fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows enhancement in the solid components of both tumors (asterisk)

Struma ovarii is suggested when a multiloculated cystic mass comprised loculi or small cysts showing low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and very low signal intensity on T2-weighted images [44] (Fig. 7). The presence of early significant enhancement on DCE MR imaging may mimic malignancy [44]. However, half of struma ovarii are mixed with dermoid cyst [45]. Thanks to the high capability of MRI or CT to perform the diagnosis of dermoid cyst, this could represent a potential clue for differential diagnosis.

Fig. 7

Images in a 53-year-old woman with bilateral struma ovarii. (a) Transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a left multiloculated cystic mass with loculi or small cysts showing very low signal intensity (arrowhead), (b) transverse fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image after gadolinium injection shows strong delayed enhancement in the solid components of the left ovarian tumor (arrow), (c, d) transverse T1-weighted MR image obtained without and with fat suppression shows left multiloculated cystic mass comprised of loculi or small cysts with low to intermediate signal intensity (arrowheads)

Granulosa cell tumors show a spectrum of imaging manifestations due to various histologic appearances and various arrangements of tumor cells. They have frequently the appearance of multiloculated cystic lesions resembling to mucinous cystadenocarcinoma [46]. These multiple cystic spaces are filled with watery fluid or hemorrhage. Similarly to mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, granulosa cell tumor is confined to the ovary at the time of diagnosis and is usually unilateral (90 %). Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary represent the most common clinically estrogenic ovarian tumor. In this setting, they are frequently associated with endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, and carcinoma (3–25 % of cases). All these features are depicted using MR imaging representing a useful tool to differentiate granulosa from malignant mucinous ovarian tumor (Fig. 8). Some unusual presentations can be confusable when rupture and hemoperitoneum occur. In all circumstances, dosage of estradiol and inhibin A should be proposed to reinforce the preoperative diagnosis of granulosa cell tumor.

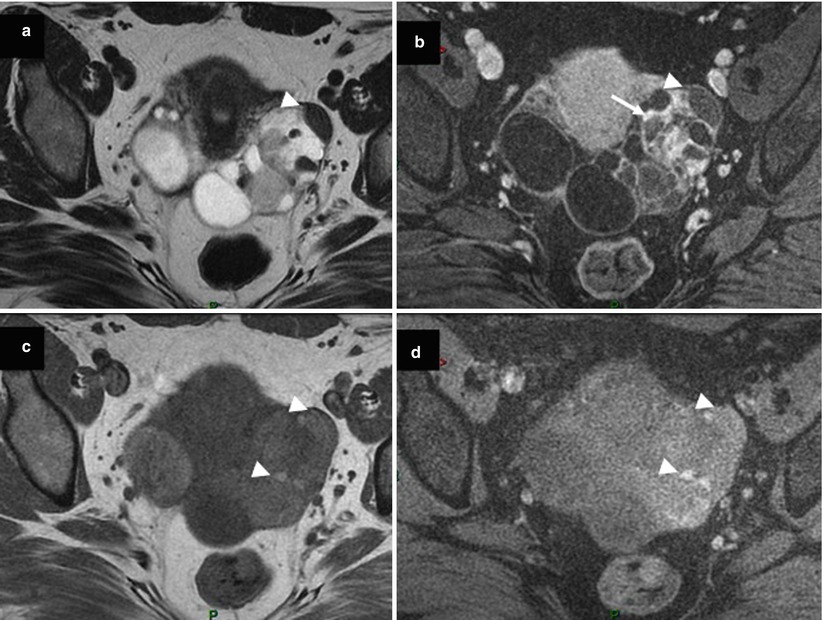

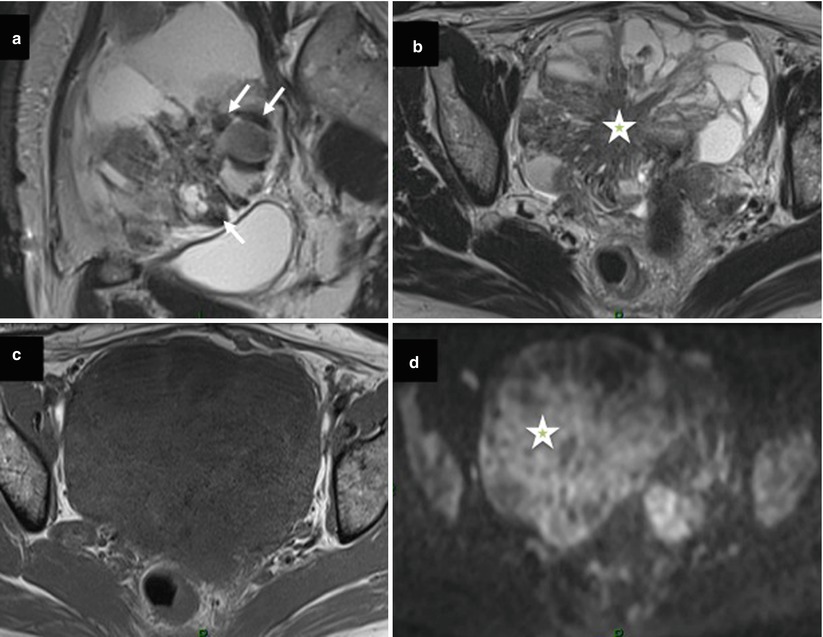

Fig. 8

Images in a 63-year-old woman with granulosa tumor. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image shows multiloculated cystic lesions with multiple cystic spaces and posterior solid mass displaying intermediate signal intensity (arrow); adenomyosis and endometrial thickening are also present (arrowhead). (b) Sagittal dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MR image shows curve type 2 within solid mass. (c) Sagittal fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image without fat suppression. (d) Sagittal T1-weighted MR image without fat suppression shows enhancement in the posterior solid mass (arrow). Adenomyosis and endometrial thickening are also visualized (arrowhead)

Metastatic tumors of the ovary, especially Krukenberg tumors, usually originate in the gastrointestinal tract. Differentiation between metastatic and primary ovarian carcinoma is of great importance with respect to treatment and prognosis. Imaging findings in metastatic lesions are nonspecific, consisting of predominantly solid components, mixed, or multiloculated cystic mass. However, Krukenberg tumor demonstrates some distinctive findings, including bilateral complex masses with hypointense solid components (dense stromal reaction) and internal hyperintensity (mucin) on T1- and T2-weighted MR images, respectively [47] (Fig. 9). In addition, the visualization of primary gastrointestinal tract, especially on multidetector CT, is sometimes possible.

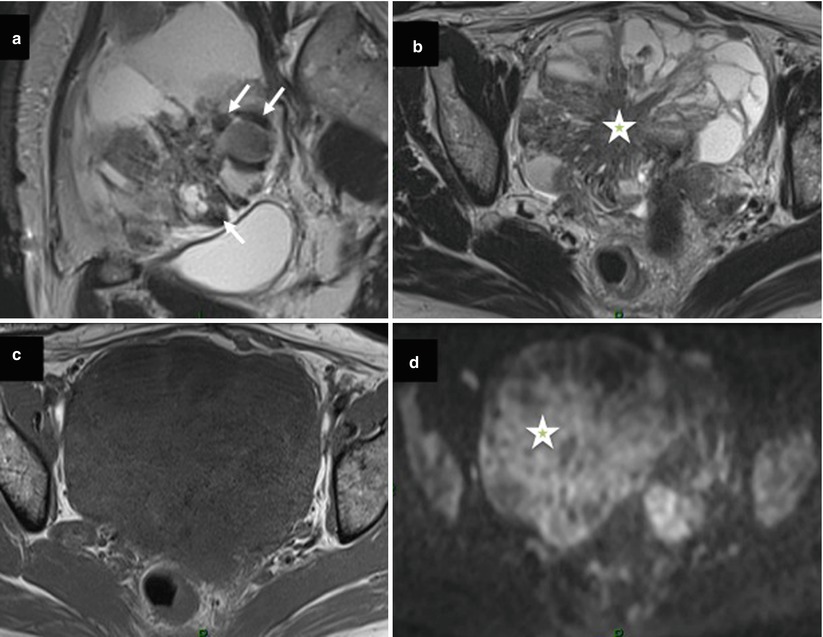

Fig. 9

Images in a 52-year-old woman with sigmoid colon cancer and bilateral ovarian metastases. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image shows a multiloculated cystic lesion and solid component with low signal intensity (arrow), (b) transversal T2-weighted MR image shows a multiloculated cystic lesion with large solid mass displaying intermediate signal intensity (asterisk), (c) transversal T1-weighted MR image without fat suppression, (d) transversal diffusion-weighted MR image shows diffuse high signal intensity in solid component (asterisk)

The possibility of collision tumor has to be suggested in a presence of unusual ovarian tumor presentation on imaging analysis. Collision tumor represents the coexistence of two adjacent but histologically distinct tumors with no histologic admixture at the interface. Even so rare, ovarian collision tumors are most commonly composed of mucinous ovarian tumors and teratoma or Brenner tumors. MRI or CT images of a collision tumor composed of a mucinous tumor (potentially malignant) and a teratoma show a typical multiloculated cystic mass with internal loculi filled with pure fat. Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma can be more difficult to differentiate from collision tumor composed of mucinous and Brenner tumors. In this setting, the presence of solid mass with intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted, high signal intensity on DWI, and a curve type 2 or 3 on DCE favors the diagnosis of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. In contrast, Brenner tumor displays very low signal intensity on T2-weighted MR sequence with mild homogeneous enhancement on postcontrast CT and MRI (Fig. 10) [48, 49]. In addition, Moon et al. demonstrated that amorphous calcification in a solid mass was a characteristic finding of Brenner tumor of the ovary on CT and MRI [49]. However, mucinous cystic ovarian tumors sometimes also contain calcifications. In a recent study, Okada et al. retrospectively investigated the radiological and histopathological evidence of calcifications in 44 cases of ovarian mucinous cystic tumors (22 benign, 13 borderline, and 9 cancers) in which a non-contrast CT scan was performed. Calcifications were noted in 34.1 % of mucinous cystic tumors on CT scans and 56.8 % in histopathological studies, and they were found in two locations, intramural and intracystic, according to the histopathological findings. Intramural calcifications were frequent in benign tumors, and intra-cystic calcifications were frequent in proliferating tumors.

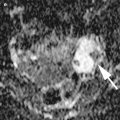

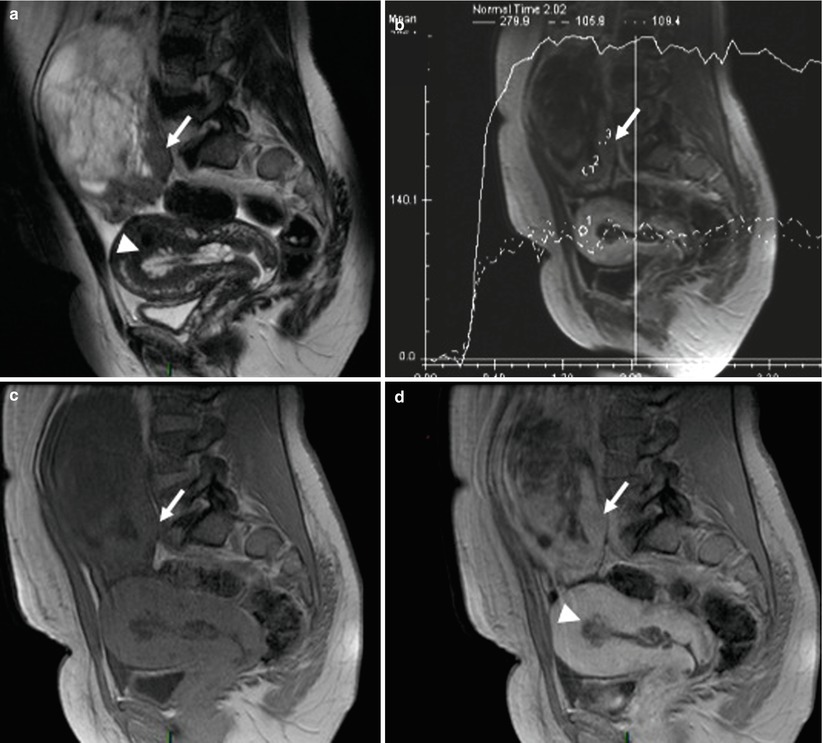

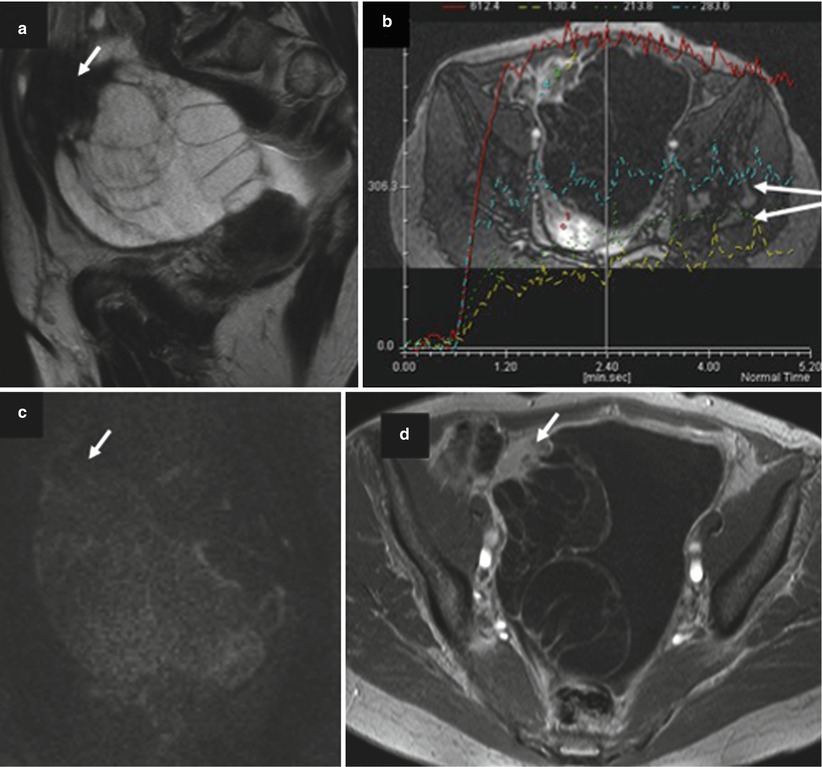

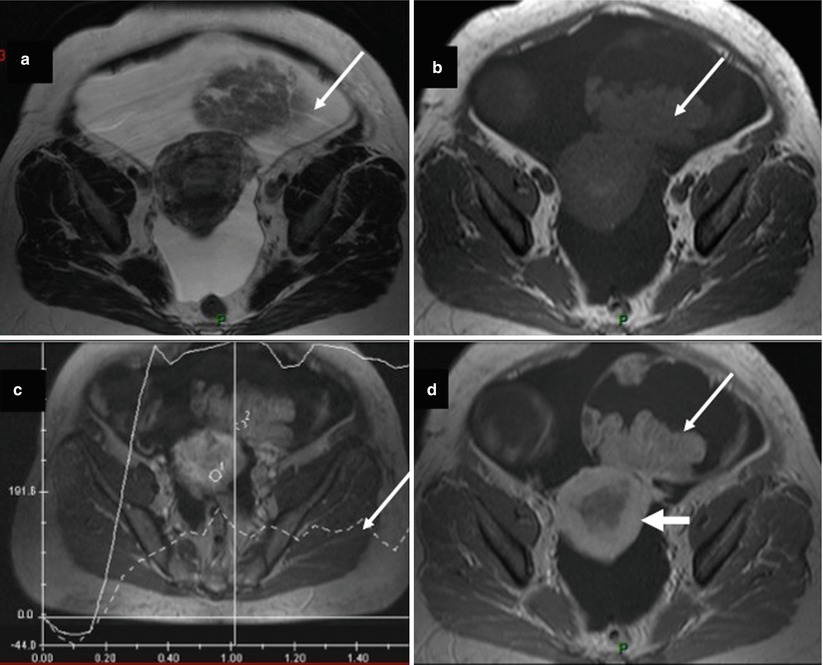

Fig. 10

Images in a 68-year-old woman with mucinous borderline ovarian tumor associated with Brenner tumor. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image shows a multiloculated cystic lesion with upper solid irregular mass displaying low signal intensity (arrow), (b) transversal dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MR image shows curves type 2 within solid mass (arrow). (c) Sagittal diffusion-weighted MR image shows the absence of high signal intensity in solid mass (arrow), (d) transversal fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression shows enhancement of irregular septa and solid mass (arrow)

Endometrioid Subtype

Endometrioid cystadenocarcinomas are almost always confined to the ovary and pelvis at the time of diagnosis [1]. Imaging findings are nonspecific and include a large, complex cystic mass with solid components. However, their association with endometriosis or endometrial disease has been previously underlined (see supra). In this setting, MR imaging represents the best imaging technique to visualize associated endometriotic lesions or endometrial thickening.

The exact prevalence of malignant tumors arising from endometriotic cysts of the ovary is unknown but is estimated of approximately 0.7 % [50]. In a recent study, Tanaka et al. confirmed that the most common histologic subtype in malignant tumors developed on pelvic endometriosis was endometrioid adenocarcinoma [50]. In this study, these authors revealed that malignant tumors associated with endometriotic cysts tended to appear in older patients (>45 years old), with larger endometriotic cysts (>10 cm) and with endometriotic cysts without shading on MRI [50]. The use of gadolinium is usually not required to differentiate blood clots (hypointense on T2 weighted) and mural nodules (intermediate on T2 weighted). However, the presence of mural nodules larger than 3 cm in maximum diameter was a strong indicator of coexisting malignancy in their study [50]. In this setting, DCE MR sequence followed by postcontrast MR imaging should be performed because enhanced mural nodules are an important finding to assess malignancy (Fig. 11). However, some exceptions, such as decidualization or endometrial polyp, should be noted to avoid potential false-positive cases of malignancy [50].

Fig. 11

Images in a 31-year-old woman with endometrioid cystadenocarcinoma grade 1 FIGO stage IA associated with endometrial cyst. (a) Transversal T2-weighted MR image shows a solid-cystic right ovarian tumor. Solid portion displays heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity (arrow). (b) Transversal T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression shows cystic component displaying intermediate signal intensity, (c) transversal T1-weighted MR image without fat suppression shows cystic component displaying intermediate signal intensity, (d) transversal fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression shows heterogeneous enhancement of solid component (arrow). Note the presence of contralateral small endometrial cyst displaying high signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images and shading on T2-weighted MR image

When the ovary and the uterus corpus are both involved by endometrioid carcinomas, the question arises whether both cancers are primary or one is metastatic from the other [51]. At histologic examination, three different possibilities are discussed. First, a direct myometrial invasion from serosal surface by ovarian tumor favors the diagnosis of ovarian primary and corpus metastasis. Second, if the endometrial carcinoma is small and limited to the endometrium or with limited myometrial invasion, and if there is a central located ovarian, sometimes arising on a background of endometriosis, the tumors are probably independent primaries [51]. Finally, if the endometrial carcinoma extends deeply into the myometrium, it is usually reasonable to conclude that the ovarian involvement is secondary [51]. These distinctions are important to consider because of the implications for treatment. In this setting, MR imaging may be a valuable tool for such differentiation, providing useful information for preoperative planning (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12

Images in a 59-year-old woman with bilateral endometrioid ovarian cystadenocarcinoma associated with endometrioid endometrial cystadenocarcinoma. (a) Transversal T2-weighted MR image shows a solid-cystic right ovarian tumor. Solid portion displays heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity (arrow). (b) Transversal T1-weighted MR image without fat suppression, (c) transversal DCE MR imaging shows a curve type 2 in right irregular solid mass, (d) transversal fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image with fat suppression shows heterogeneous enhancement of solid component (arrow). Note endometrial irregular thickening related to endometrial carcinoma (large arrow)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree