George M. Bridgeforth, Shane J. Nho, Rachel M. Frank, and Brian J. Cole

A 25-year-old woman who fell on her right arm complains of marked pain and soreness around her right collarbone.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Most clavicle fractures affect the middle third of the bone.

- Fractures affecting the medial third of the bone may be associated with more serious thoracic injuries.

- Most of these fractures heal without serious sequelae; however, complications can occur.

Clinical Presentation

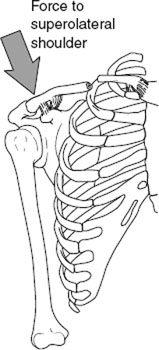

The clavicle is the only bony connection between the upper arm—shoulder and the thorax. It is the most frequently broken bone in the human body. The clavicle is divided into thirds. Fractures of the middle third are the most common, accounting for 80% of cases. Many of these fractures are caused by direct blows or falls, including falls onto an outstretched hand. Fractures of the lateral third account for 15% of cases. Generally, these types of fractures are caused by a direct impact injury at the top of the shoulder (Fig. 31.1). Fractures of the medial third account for 5% of cases and are usually caused by direct chest trauma. Patients with clavicle fractures complain of marked pain, particularly with movement; swelling and bruising; and tenderness.

The clinician should evaluate clavicle fractures, especially those involving the medial and middle thirds, for any associated thoracic and cervical injuries. It is essential to treat any associated cervical injury as an unstable acute spinal cord injury until it is proven otherwise. Stabilization of the patient on a spine board and in a hard cervical collar is necessary until a cervical injury is excluded by radiographs and a computed tomography scan. Thorough examination of the patient’s neurovascular status (associated compartment syndrome, cold cyanotic limb with decreased or absent pulses), with careful documentation, is necessary.

It is important to examine the acromioclavicular (AC) joint and the upper humerus for any evidence of associated swelling and ecchymosis. Lateral clavicular fractures may be associated with AC joint separations or upper humeral fractures. It is necessary to palpate the humeral head and neck (Fig. 31.2). In the AC joint, there may be a nondisplaced fracture, a grade 1 joint separation, or a step-off deformity with possible fracture displacement. In addition, the clinician should inspect the shoulder girdle for any acute dislocations. In addition, the clinician be on the alert for several associated conditions.

It is necessary to strongly consider a thorough chest examination with rib films if there is accompanying chest wall trauma. Radiographs show an effacement of the vascular tree. Sometimes with smaller pneumothoraces (<10%), the effacement may hide in the apical portions of the lungs. This is easy to miss (Fig. 31.3).

FIGURE 31.1 The most common mechanism of clavicle fracture is a fall on the superolateral shoulder. Since the sternoclavicular ligaments are extremely strong, the force exits the clavicle in the midshaft. (From Bucholz RW and Heckman JD. Rockwood & Green’s Fractures in Adults. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2001.)

FIGURE 31.2 An anteroposterior radiograph of the right shoulder in a 30-year-old patient who was involved in a motorcycle collision, demonstrating an acute fracture through the distal third clavicle (arrow) and widening of the acromioclavicular joint by 16 mm.

The examiner should also check for any focal chest wall tenderness associated with absent breath sounds (and hyperresonance to percussion), which is suspicious for an associated pneumothorax. Patients with an effusion have shortness of breath, dullness at the bases (if they are able to sit up), and absent breath sounds. Radiographs show blunting of the affected diaphragm(s). The normally sharp costophrenic angle is effaced with an effusion. A pneumothorax may occur with or without an associated chondral (rib) or clavicular fracture. A tension pneumothorax is rare, but it is characterized by an acute pneumothorax that is associated with tracheal deviation. The ruptured lung operates like a one-way valve. It allows air to accumulate in the pleural space (between the pleural lining and the collapsed lung) during inspiration. As the pressure in the pleural cavity increases, it can cause deviation of the trachea and move the cardiac structures to the opposite side. Decompression with chest tube placement must be performed immediately.

FIGURE 31.3 A portable chest radiograph in a trauma patient, demonstrating an acute right clavicle fracture (arrow) associated with a moderate-sized right pneumothorax (arrowheads). A computed tomography scan of the chest demonstrated nondisplaced fractures of the right ribs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree