Suyash Mohan, MD, PDCC, and Laurie A. Loevner, MD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. To recognize and describe the relevant radiologic characteristics of a cystic lesion in the head and neck on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US)

2. To identify the anatomic location of a cystic lesion within the neck spaces and formulate an appropriate differential diagnoses based on anatomical location

3. To incorporate pertinent clinical information in narrowing the differential diagnosis and form a concise impression (e.g., pediatric versus adult patients, acute versus chronic presentation, tender versus painless lump, associated infectious/inflammatory signs versus asymptomatic)

4. To suggest appropriate follow-up and recommend cost-effective diagnostic workup and prompt communication of emergent findings

There are various causes of cystic lesions in the head and neck, including congenital lesions, infectious/inflammatory conditions, lymphatic malformations, trauma, lymphadenopathy, and neoplasm (Table 18.1) (1–6). The overwhelming majority of cystic neck lesions in newborns and infants are benign (congenital or developmental). In children, infectious/inflammatory etiologies are more common than neoplastic etiologies, whereas in adults, neoplastic etiologies are more common than infectious/inflammatory etiologies. The most common congenital cystic lesions in the neck are thyroglossal duct cysts (TGDCs), lymphatic malformations, and branchial apparatus anomalies. In adults, cystic neck nodal metastasis can mimic benign congenital lesions, and tissue sampling in an adult is necessary to exclude malignant neoplasm/metastatic adenopathy (4,7–10).

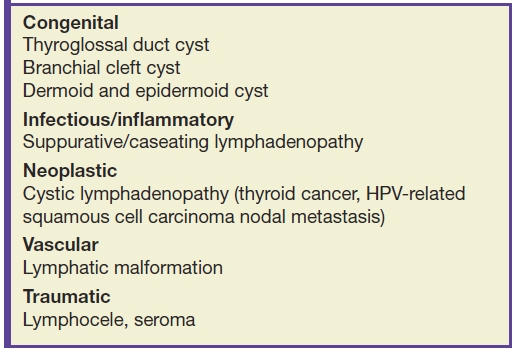

Table 18.1 Common Cystic Lesions in Head and Neck by Etiologies

Although clinical history and examination may suggest the diagnosis, imaging is critical to confirm the clinical suspicion, accurately assess the complete anatomical extent of the lesion, and plan for treatment. High-resolution ultrasound (US) is an ideal initial imaging investigation, especially in the pediatric population, as it reveals the cystic nature in most cases and localizes the mass in relation to the surrounding structures. Additionally, advances in US technology with the advent of three-dimensional and four-dimensional techniques, color, and power Doppler have led to great improvement in its diagnostic utility. Imaging is real time, free of harmful radiation, and cost-effective and does not need sedation. Computed tomography (CT) remains the most widely used modality with its superior spatial resolution and is especially useful for the evaluation of deep neck infection such as retropharyngeal abscess as well as for demonstration of calcification or fat within the lesion. Both US and CT are valuable image guidance tools for safe and accurate tissue sampling, further assisting diagnosis and treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a complimentary role in workup of cystic neck masses, provides multiplanar capabilities and superior contrast resolution, and allows precise preoperative anatomical localization, particularly for more deep-seated and locally extensive lesions (5,11). Table 18.2 summarizes the classic imaging findings of cystic lesions in the head and neck.

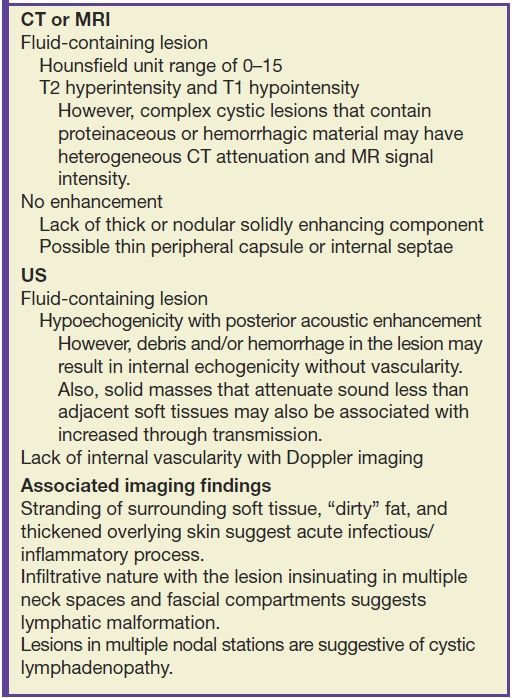

Table 18.2 Imaging Criteria of a Cystic Lesion

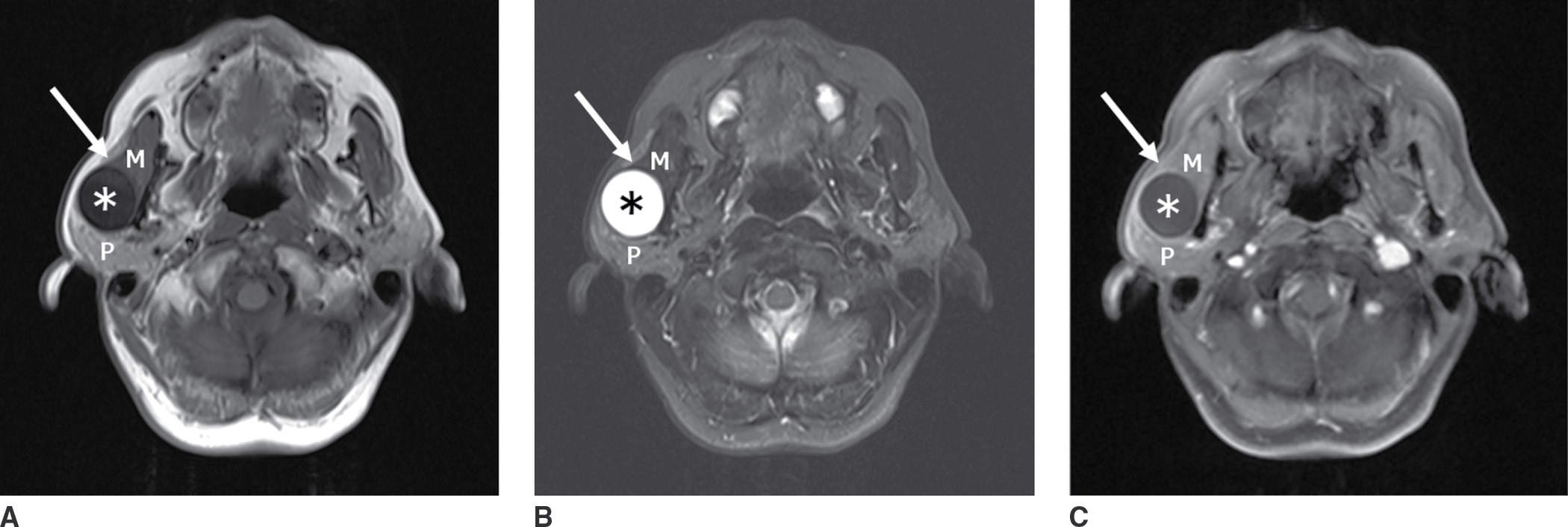

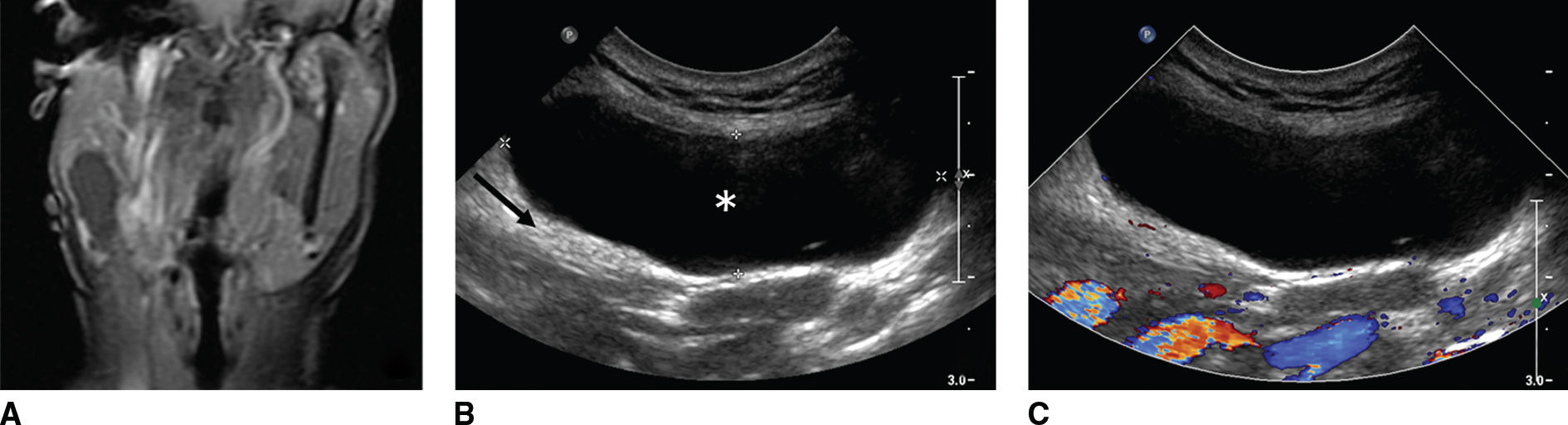

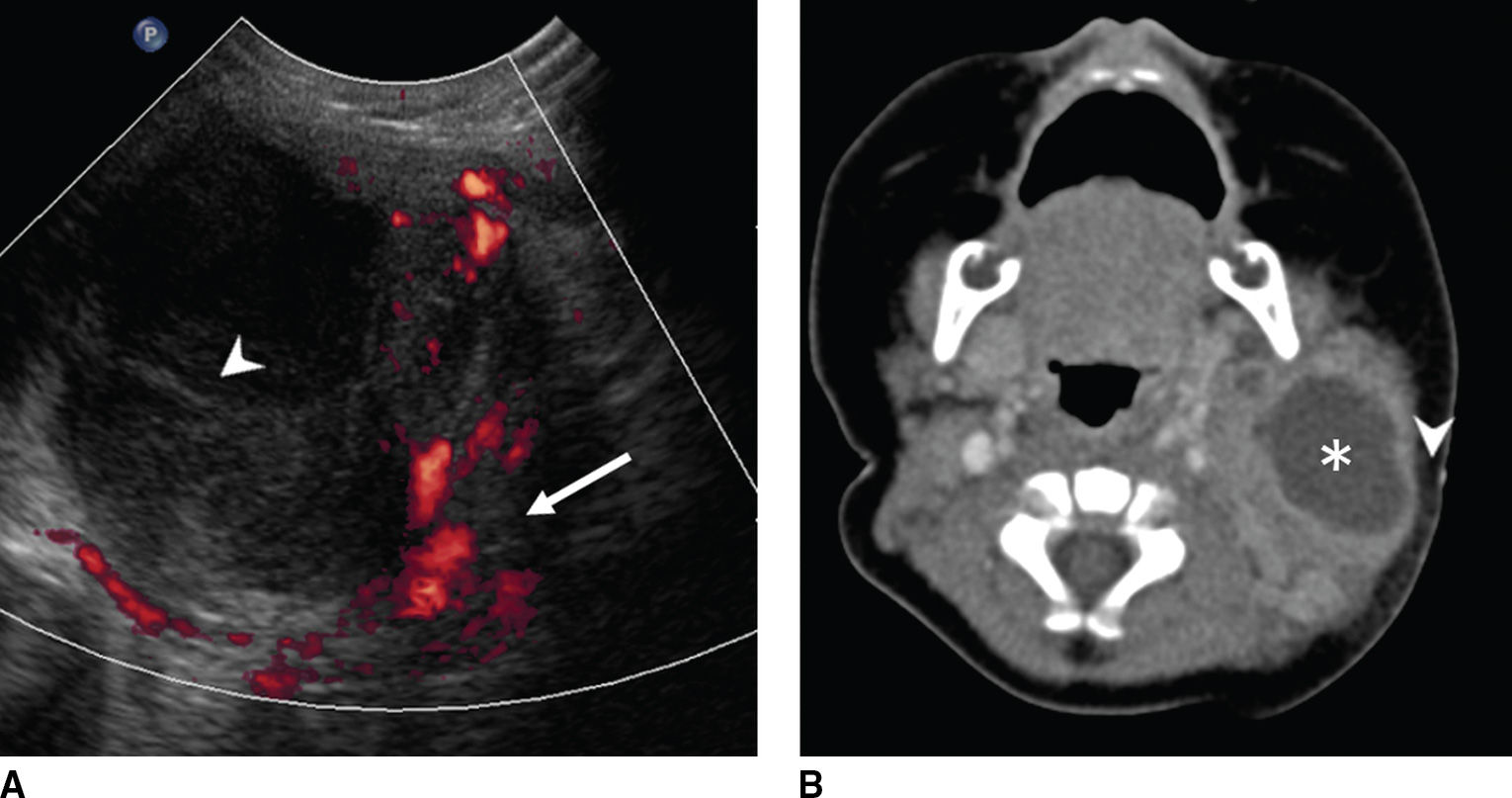

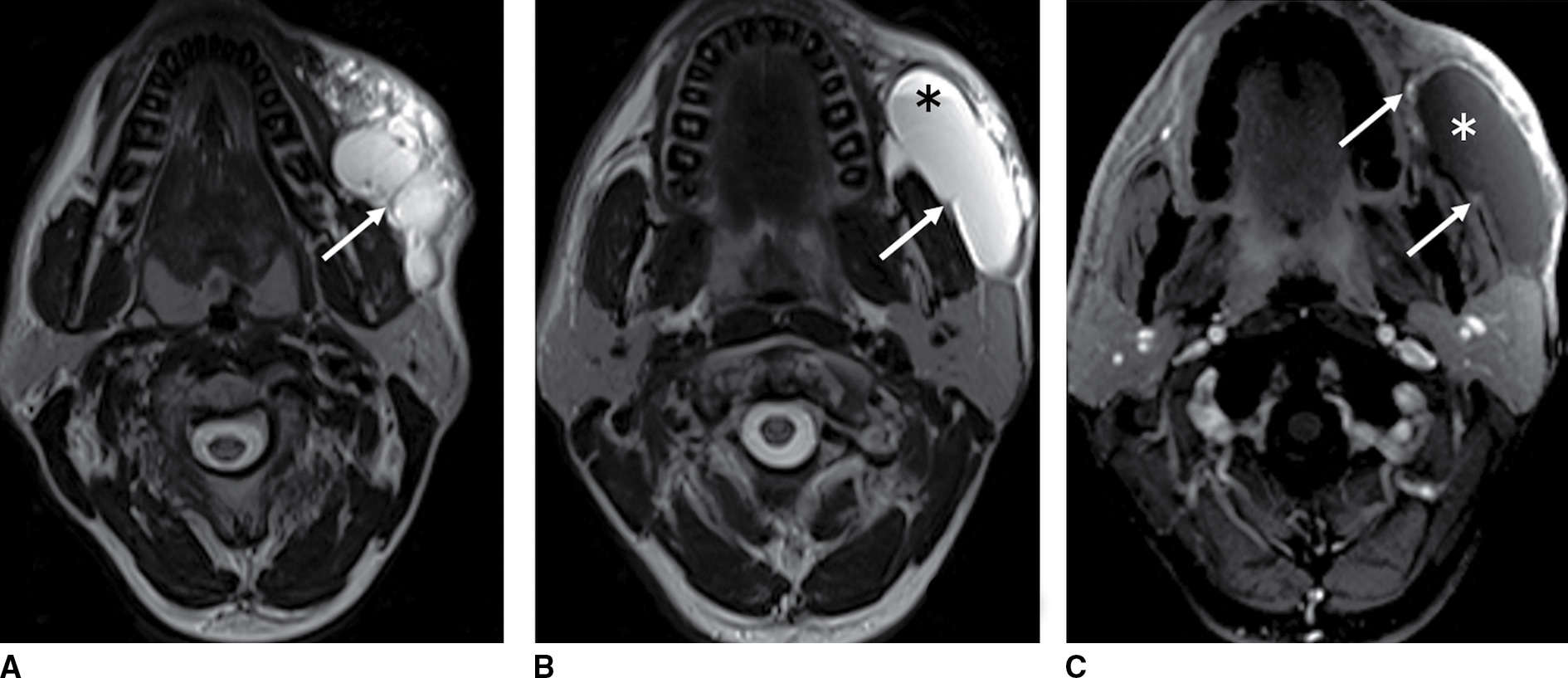

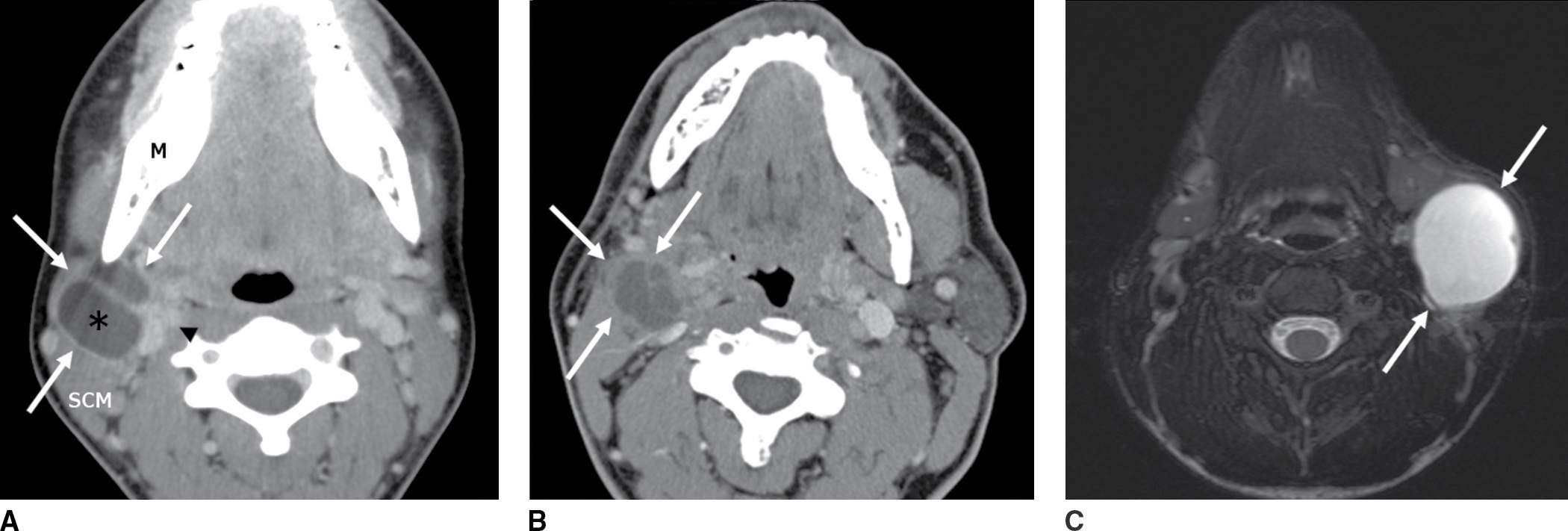

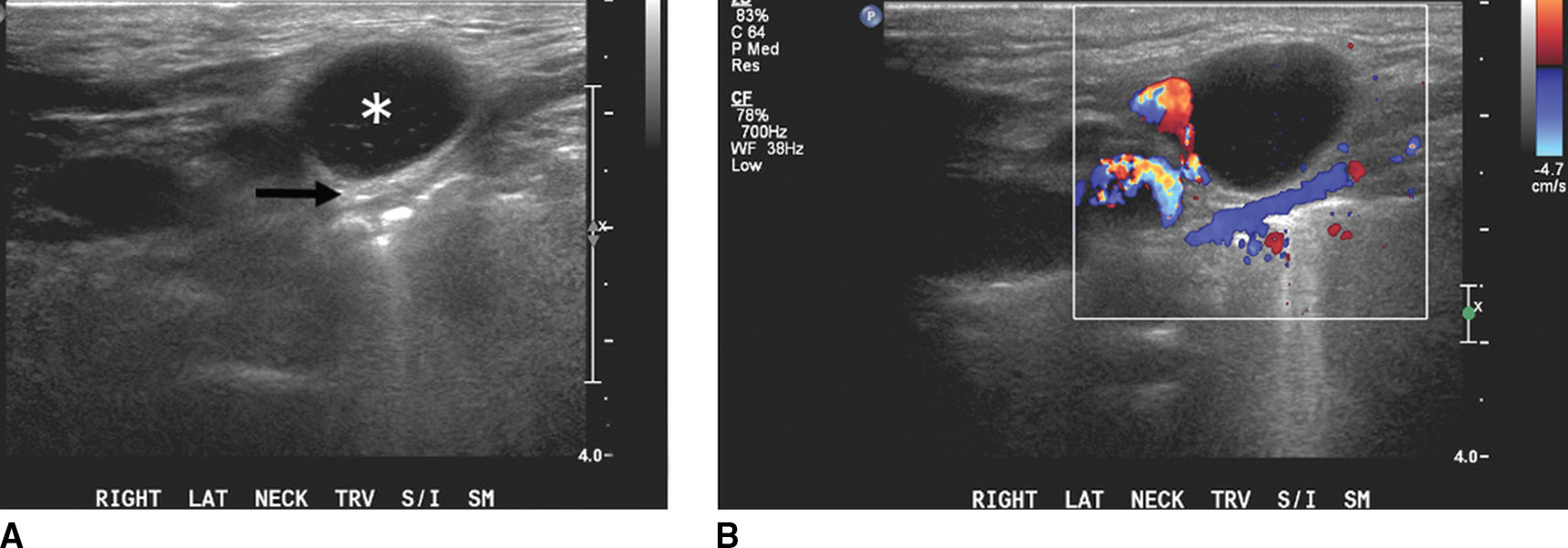

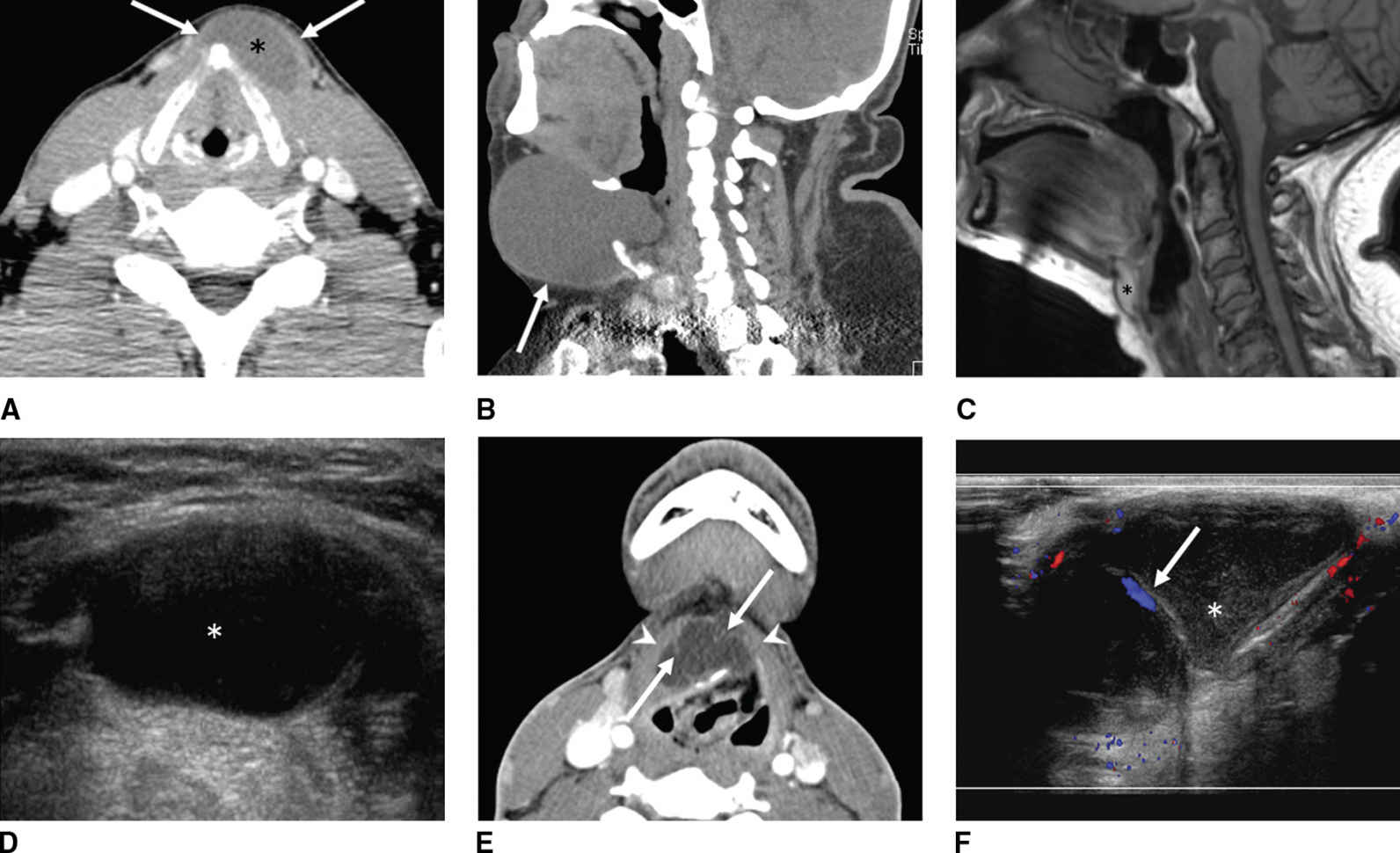

On CT and/or MR imaging, cystic neck lesions are usually fluid containing, with imperceptible or thin barely perceptible walls demonstrating no or minimal enhancement (Fig. 18.1). On US, a cystic lesion is anechoic to hypoechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement on gray scale and typically lacks internal vascular flow on color Doppler (Fig. 18.2). Internal heterogeneity, thin internal septations, layering or floating particles, and fluid–fluid levels may be seen in cystic lesions corresponding to proteinaceous material, hemorrhage, and/or infectious debris (Figs. 18.3 and 18.4). Superimposed hemorrhage and/or infection within a cystic lesion may result in wall thickening and internal septations (Figs. 18.4 and 18.5). A partially necrotic neoplasm or adenopathy should be considered if there is any suggestion of an enhancing nodular solid soft tissue component on CT or MRI and/or internal vascular flow on US (Figs. 18.5 and 18.6). In sum, complex fluid content in a cystic lesion can mimic neoplasm, but lack of solid enhancement on CT and MRI and lack of vascularity on Doppler US confirm its cystic nature.

FIG. 18.1 MR characteristics of a cystic lesion in a 70-year-old man with painless fluctuating mass over the right lateral jaw. A: Axial T1-weighted image shows a well-circumscribed cystic lesion (asterisk) along the posterior margin of the masseter muscle (M). B: Axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows T2 hyperintense fluid signal of the lesion (asterisk) with imperceptible walls and no internal septations. C: Axial enhanced T1-weighted fat-suppressed image shows no enhancement. Note a claw sign with muscle tissue (arrow) around the anterior margin of the cyst, placing its origin in the masseter muscle rather than parotid gland (P). Differential: lymphatic malformation, first branchial cleft cyst, parotid cyst.

FIG. 18.2 Ultrasound characteristics of a cystic lesion in a 44-year-old woman with recurrent parotid cyst. A: Coronal enhanced T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a hypointense nonenhancing lesion in the right parotid tail. B,C: Gray scale and color Doppler US, respectively, show a hypoechoic lesion (asterisk) with posterior acoustic enhancement (arrow), and color Doppler shows no internal vascularity. Fine-needle aspiration yields straw-colored fluid containing some macrophages and results in near complete collapse of the cyst. Differential: first branchial cleft cyst, parotid cyst, sialocele.

FIG. 18.3 Suppurative lymphadenitis with abscess formation in a 3-month-old febrile baby with enlarging left neck mass and overlying skin erythema and edema. A: Color Doppler US shows a complex, cystic lesion that contains both hypervascular soft tissue (red, arrow) and avascular necrotic tissue (arrowhead). B: Axial enhanced CT image shows corresponding cystic mass with mild increased density due to protein content (asterisk) and extensive surrounding soft tissue and stranding of the subcutaneous fat (arrowhead).

FIG. 18.4 Lymphatic malformation in a 30-year-old man with sudden enlarging and tender cheek mass. A,B: Axial T2-weighted MR images show a T2 hyperintense transpatial, multilobular cystic mass with thin walls and internal septation (arrows). A fluid–fluid level (asterisk) reflects recent hemorrhage. C: Axial enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows no solid enhancement (asterisk) but mild enhancement of the septation as well as the periphery (arrows).

FIG. 18.5 A: A 17-year-old adolescent with a painless palpable neck lump that developed after a cold. Axial enhanced CT image shows a septated cystic lesion (asterisk) with peripheral enhancement and thin enhancing septae (arrows). It is behind the mandibular angle (M), anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), and lateral to the carotid sheath (arrowhead) typical of a second branchial cleft cyst. B: A 60-year-old man with right tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma and a painless, palpable metastatic IIA lymph node. Axial enhanced CT image shows a low-attenuation complex cystic lesion similar in location and appearance to case A, with enhancing rim and septae (arrows). In an adult, a cystic neck mass in the cervical lymph chain is cancer until proven otherwise. C: A 5-year-old girl with painless neck mass. Axial T2-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a circumscribed hyperintense cyst with a thin/imperceptible rim (arrows) in the classic location for second branchial cleft cyst.

FIG. 18.6 Malignant lymphadenopathy in an elderly man with persistent neck mass unresponsive to antibiotics. A: Grayscale US shows a hypoechoic lymph node (asterisk) with posterior acoustic enhancement (arrow) and loss of the normal fatty hilum and nodal architecture. B: Color Doppler US illustrates internal vascularity, consistent with a solid pathologic lymph node. C: Axial enhanced CT image confirms bilateral level IIA lymphadenopathy, solid on the right (arrows) and necrotic on the left (arrowhead). Biopsy revealed B-cell lymphoma.

Congenital and developmental lesions are typically long-standing and commonly present as a painless fluctuating lump in the pediatric age group, but can present in late adulthood as well. These are usually disfiguring and externally visible, but their detection may follow sudden and rapid enlargement from infection and/or hemorrhage (Fig. 18.4), with the possibility of life-threatening airway obstruction in infants. Infectious and inflammatory lesions, though more common in young adults, can present in any age group (Fig. 18.7). Recurrent neck infection of unclear etiology is also a known presentation of congenital lesions, such as cyst, sinus, or fistula (Fig. 18.8). Occasionally, a cystic or necrotic neoplasm can mimic a congenital cyst, and therefore, a cystic neck lesion without obvious signs of infection in an adult needs thorough clinical evaluation and tissue diagnosis to exclude necrotic lymphadenopathy (Figs. 18.5 and 18.9). Any cystic lesion in an adult should be considered malignant until proven otherwise, particularly with the advent of HPV-related squamous cell carcinomas, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy should be considered.

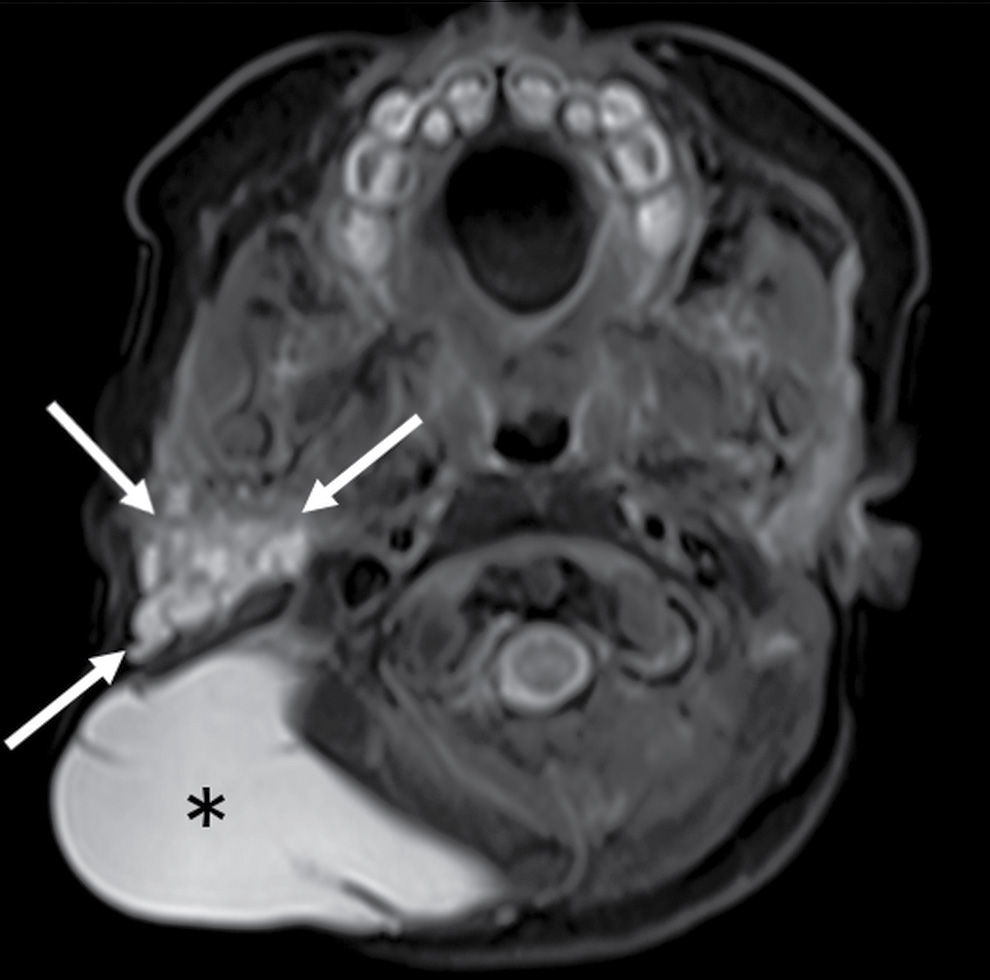

FIG. 18.7 Lymphatic malformation in a 3-day-old girl with a large cystic right neck mass. Axial T2-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a multispatial, T2 hyperintense cystic mass in the posterior triangle (asterisk). Small cystic spaces extend into the right parotid and masticator spaces (arrows), consistent with cystic hygroma lymphatic malformation.

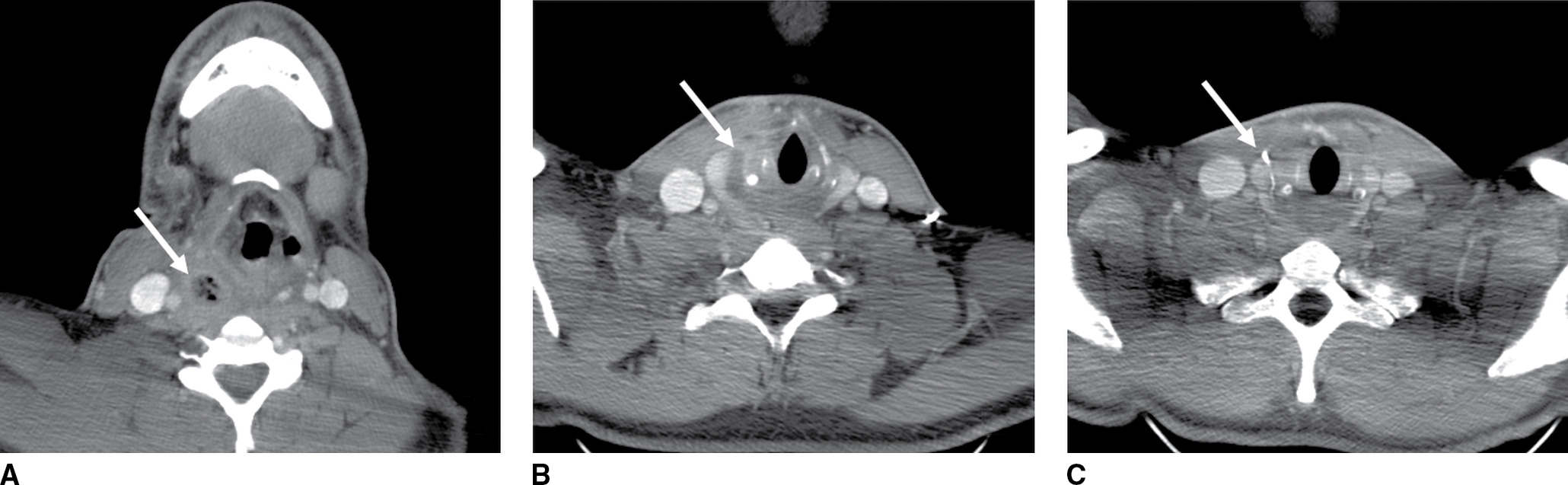

FIG. 18.8 Recurrent infection of fourth branchial cleft fistula in a 23-year-old man with multiple episodes of recurrent right neck infection since 6 years of age. A: Axial enhanced CT shows rim-enhancing abscess (arrow) in the right retropharyngeal space containing air raising the possibility of an aerodigestive tract fistula. B: Axial enhanced CT shows inferior extension of the collection (arrow) medial to the thyroid gland. C: Axial enhanced CT at 6-month follow-up performed after barium swallow study shows a linear tract of barium (arrow) medial to the thyroid at the site of the previous collection confirming the presence of a congenital fistula.

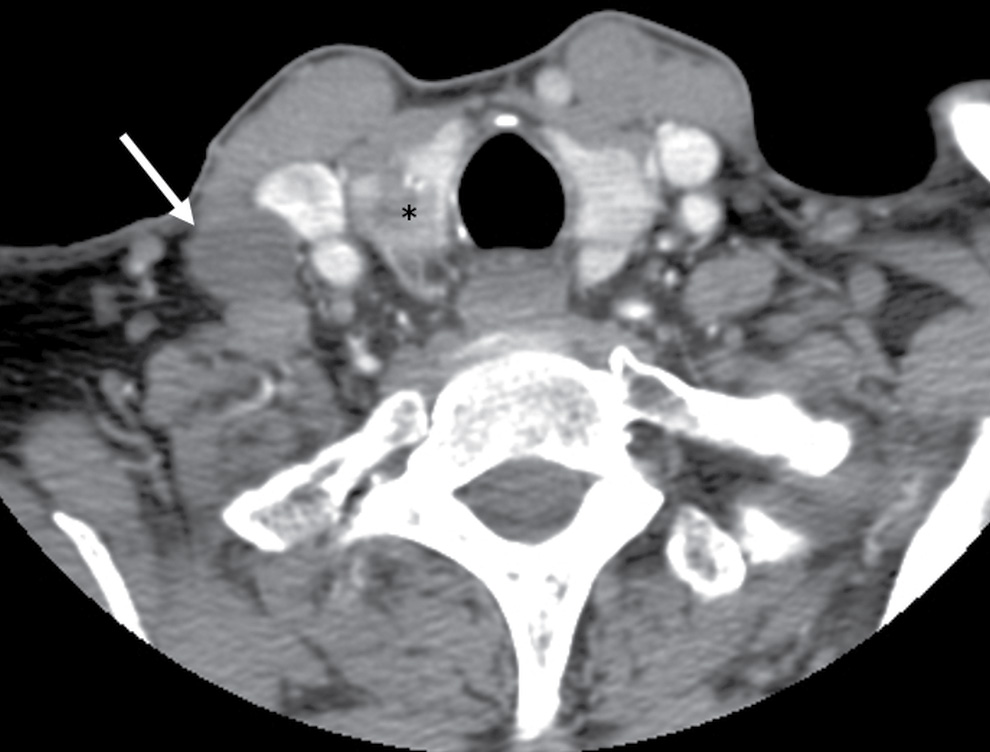

FIG. 18.9 Cystic lymph node metastasis in a 67-year-old woman with painless, palpable right neck mass. Axial enhanced CT shows a cystic lymph node (arrow) with thin/imperceptible margins from a primary papillary cancer in the right thyroid lobe (asterisk).

Treatment of the symptomatic congenital cystic lesion is complete surgical resection to minimize recurrence. Sclerotherapy has also been a successful minimally invasive option for carefully selected macrocystic lymphatic malformations. The treatment of neoplastic cystic lesions is tailored to the specific pathology, disease stage, and comorbidities.

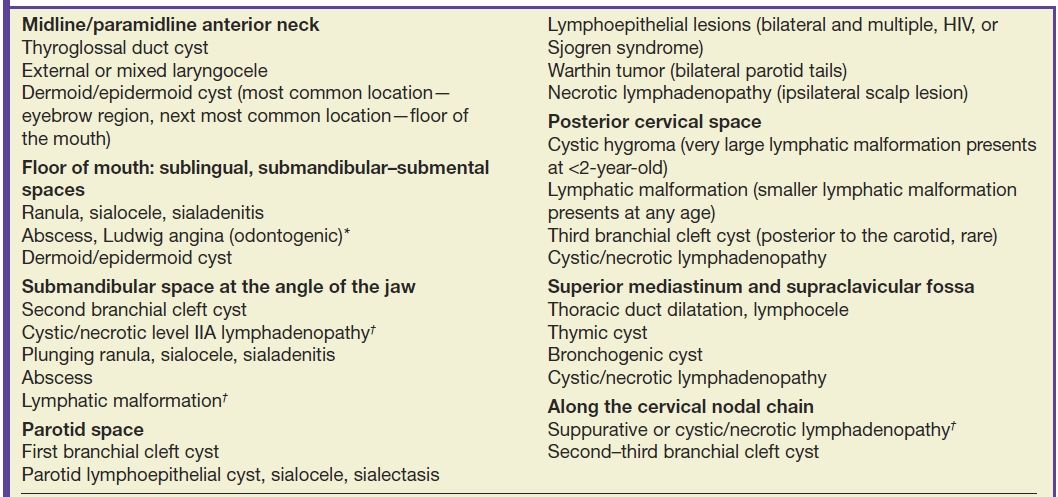

Table 18.3 groups the most common differential diagnoses of the cystic lesions in the head and neck by their clinical as well as imaging anatomical locations. The following discussion will succinctly review the key concepts pertaining to common cystic lesions in the neck.

Table 18.3 Common Cystic Lesions in the Head and Neck by Clinical and Imaging Anatomic Locations

*Neck abscesses are commonly secondary to an odontogenic infection or secondary to pharyngitis/tonsillitis and also commonly occur in peritonsillar/retropharyngeal spaces.

†Cystic/necrotic lymphadenopathy most commonly represents suppurative adenopathy in children and nodal metastasis from thyroid cancer or HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma in adults.

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst

A TGDC is the most common congenital neck mass, accounting for 70% of all congenital neck anomalies (1,2,6). Embryologically, the thyroglossal duct (which means pertaining to the thyroid gland and the tongue) extends from foramen cecum in the base of the tongue to the thyroid bed through the hyoid bone. Any portion of this duct that fails to involute results in a TGDC. It is located in the midline (75%) or slightly paramidline (25%) and embedded in the infrahyoid strap muscles. The most common location of a TGDC is infrahyoid (65%), whereas only 15% are at the level of the hyoid bone, and 20% are suprahyoid in the location in the anterior neck. The more inferior the cyst, the more likely it is to be off the midline. About 50% of patients present before 20 years of age, though there is a small percentage (15%) who present at older than 50 years, with no reported gender predilection.

The most common clinical presentation is that of a painless palpable cystic neck mass near the hyoid bone in the midline Approximately one-third present with a concurrent or prior infection. As a result of their intimate relationship with the foramen cecum and hyoid bone, the TGDC usually moves with swallowing or protrusion of the tongue on physical exam (5,6,12).

The uncomplicated TGDC can be anechoic, homogeneously hypoechoic, or heterogeneous in echogenicity on US, without internal vascularity on color Doppler US. The uncomplicated TGDC is well defined with low CT attenuation, has fluid signal intensity on MR, and lacks solid enhancing component (Fig. 18.10). The thin cyst wall may demonstrate peripheral contrast enhancement. A complicated TGDC with superimposed infection may have peripheral contrast enhancement and internal septations and may be associated with edema and stranding of the surrounding soft tissues. Ectopic thyroid tissue may be present in the TGDC and can be a site of thyroid carcinoma, 80% of which are of papillary cell origin (Fig. 18.11).

FIG. 18.10 Thyroglossal duct cysts (TGDC). A: A 42-year-old man with painless, palpable anterior midline neck mass that moves with swallowing. Axial enhanced CT shows a left paramedian low-density cystic lesion (asterisk) embedded within the strap muscles (arrows). B-D: A 59-year-old man with an enlarging midline anterior neck TGDC (arrow). C,D: Thyroglossal duct cyst at hyoid level. C: Sagittal T1-weighted MR image shows high signal intensity in a TGDC at the hyoid level due to proteinaceous contents. D: Corresponding US shows the cystic nature of the lesion. E,F: A 20-year-old man with acute enlargement of a midline neck mass. E: Axial enhanced CT shows a complex thyroglossal duct cyst characteristically embedded in the strap muscles (arrowheads). Note thin internal septations (arrows). F: Corresponding sagittal color Doppler US shows nonvascular internal echogenic debris (asterisk) and vascular septa (arrow).

FIG. 18.11 Papillary thyroid carcinoma in a thyroglossal duct cyst in a 53-year-old woman with prior total thyroidectomy for a large compressive goiter with clinically palpable anterior midline TGDC. A: Color Doppler evaluation of the palpable lesion shows internal vascularity (arrowhead) of the hypoechoic nodule (arrow), compatible with solid tissue in the TGDC. B,C: Sagittal unenhanced T1-weighted and enhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted images, respectively, confirm solid enhancing nodule (arrow) associated with the TGDC.

The surgical resection of a symptomatic TGDC is Sistrunk procedure, which involves resection of the thyroglossal remnant together with a central portion of hyoid bone and cuff of tissue around the thyroglossal tract from the hyoid bone to the foramen cecum (12).

The diagnosis of a TGDC can be made preoperatively in most cases, based on typical clinical and imaging findings. The presence of a solid component or an enhancing nodule within a TGDC on imaging should raise suspicion for carcinoma.

Laryngocele

The laryngeal ventricle is the slit-like cavity between the false vocal cord above and true vocal cord below, which extends superiorly in the paraglottic space. A laryngocele is a dilatation of the laryngeal saccule, a small pouch arising from the roof of the laryngeal ventricle. When this saccule extends above the superior border of the thyroid cartilage, it is considered a laryngocele (1). The internal laryngocele is confined by the thyrohyoid membrane and is contained in the paraglottic space, whereas the external laryngocele extends through the thyrohyoid membrane to be lateral to the thyrohyoid membrane.

They typically develop as a consequence of chronically increased intraglottic pressure, common in wind instrumentalists and glass blowers, and possibly in combination with a congenitally large saccule. Although most laryngoceles are found incidentally, large internal laryngoceles can be symptomatic and cause hoarseness or dysphagia; external laryngoceles can present as a palpable mass and occasionally can get infected, called a pyolaryngocele. Most importantly, they may develop because of an underlying obstructive lesion in the laryngeal ventricle, alerting radiologists to scrutinize the larynx for presence of a mass.

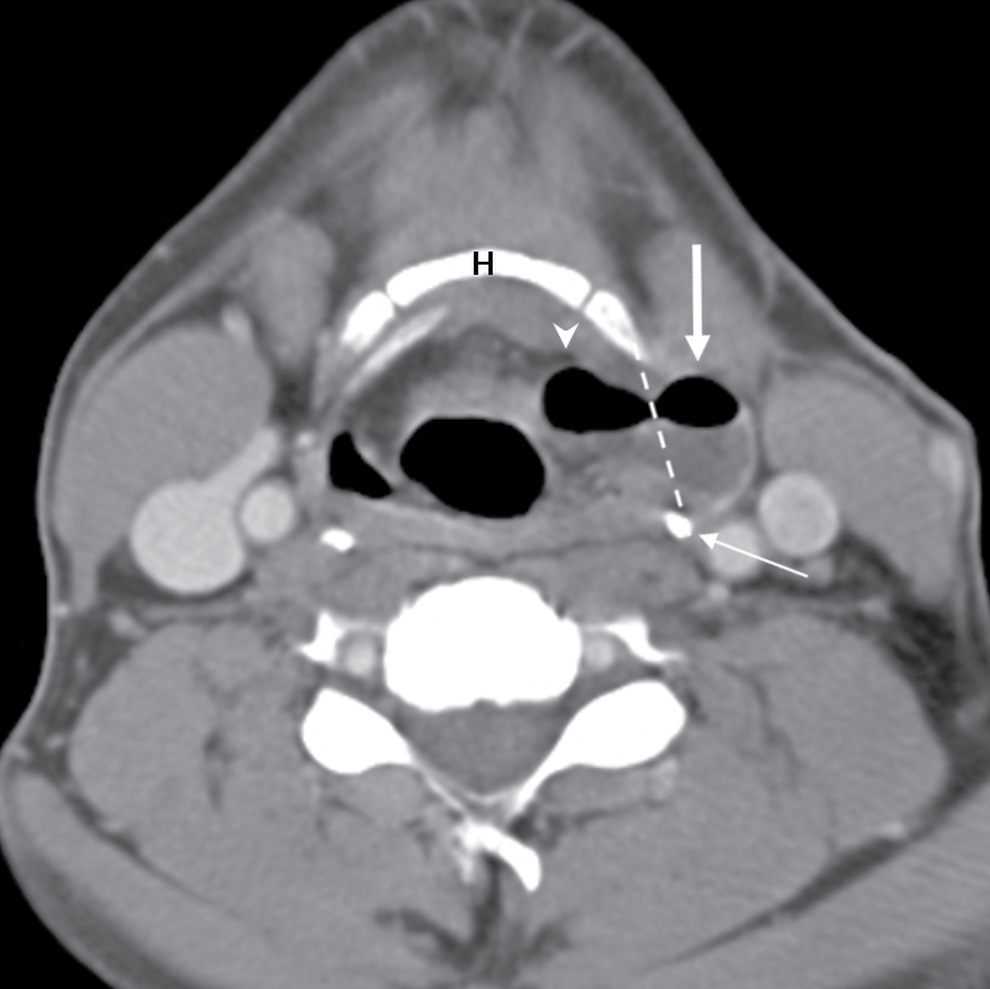

On CT and MRI, a laryngocele appears as well-defined lesion in the paraglottic location. Laryngoceles can contain air, fluid, or an air–fluid level, but the presence of a soft tissue mass within it suggests an underlying laryngeal neoplasm. The uncomplicated laryngoceles typically contain fluid, air, or a combination thereof without associated enhancing mass lesion (Fig. 18.12). Symptomatic or infected laryngocele can be aspirated and surgically resected, and laryngoscopy examination is critical for evaluation of an obstructive lesion in the larynx.

FIG. 18.12 Mixed laryngocele in a 44-year-old man with an air- and fluid-filled laryngocele in the left paraglottic space (arrowhead), which protrudes through the thyrohyoid membrane (dotted line) to have an external component (arrow).Hyoid bone (H), thyroid cartilage (thin arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree