Fig. 7.1

Position of the probe during the examination of the great saphenous vein in a standing subject. 1 Examination of the saphenofemoral junction, 2 measurement of the saphenous vein diameter in the thigh

Copyright: [Author]

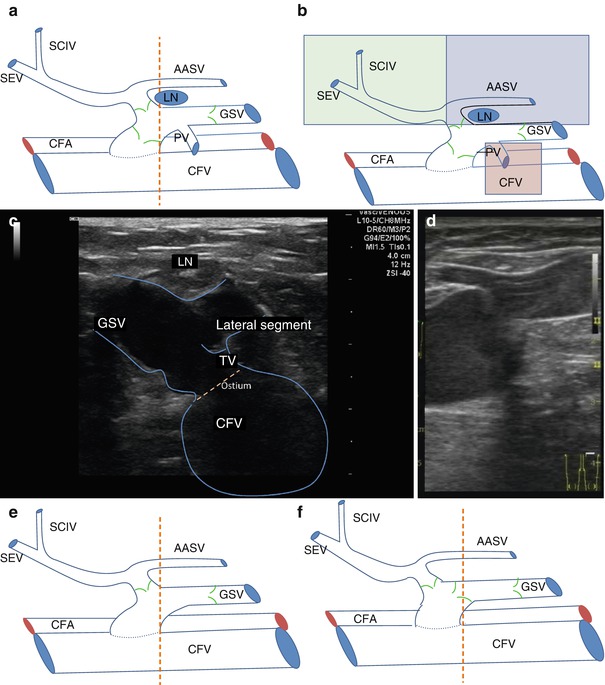

The superficial tributaries at the saphenofemoral junction (Sect. 2.4) have many anatomical variants which are important to evaluate using duplex ultrasound because this may influence the treatment approach (Fig. 7.2; see also Sect. 7.3.6). It is helpful during surgery if the surgeon knows how many tributaries are expected and how they connect. Occasionally it is difficult to define whether the surgically exposed vein is the junction of the anterior accessory saphenous vein with the great saphenous vein or the true junction of the great saphenous vein with the common femoral vein. This situation is easily avoided if the operator knows exactly how many tributaries join the great saphenous vein at the saphenofemoral junction and their distribution towards lateral and medial. Furthermore, the division of the epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac veins into two or three branches which join the anterior accessory saphenous vein can likewise make this junction look like the saphenofemoral junction, thus adding to the confusion (Fig. 7.2 C, D, I, L, M, O, P and Sect. 7.3.1).

Fig. 7.2

Views of the different confluence variations of the great saphenous vein, its tributaries and the confluence of the superficial inguinal veins with the common femoral vein according to Lanz and Wachsmuth. 1 Falciform margin of the saphenous hiatus with 2 upper cornu and 3 lower cornu. 4 Deep inguinal lymph nodes. 5 Common femoral vein. 6 Common femoral artery. 7 Femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, 8 Cutaneous branch of the femoral nerve. 9 Great saphenous vein. 10 Anterior accessory saphenous vein. 11 Superficial circumflex iliac vein. 12 Superficial epigastric vein. 13 Superficial external pudendal vein. 14 Posterior accessory saphenous vein (legends for letters – see text) (From Platzer (2005); by kind permission of Thieme-Verlag)

Copyright: Thieme

The veins of the confluence of the superficial inguinal veins are:

Some of these veins may not be present. Many of them, especially the proximally arising superficial circumflex iliac and the superficial epigastric veins, have several sub-tributaries which may join to form a single vein at the saphenofemoral junction or enter the confluence of superficial inguinal veins separately. The same is true of the medially arising superficial and deep external pudendal veins which often join the common femoral or the posterior accessory saphenous vein directly. Furthermore, all or any of these veins may join one another before they enter the confluence of the superficial inguinal veins.

Lanz and Wachsmuth have systematised all the possible anatomical variations of the confluence (Fig. 7.2). They start with the confluence of all the superficial inguinal veins into the common femoral vein (A) and then describe the different variants for the confluence of the individual vessels: B–E for the anterior accessory saphenous vein; F–G for the posterior accessory saphenous vein; H–I for the superficial and deep external pudendal veins, respectively; J–N for the superficial epigastric vein; and O–R for the superficial circumflex iliac vein.

7.3.1 Normal Findings

The great saphenous vein joins the common femoral vein from the anteromedial aspect. As a rule a competent great saphenous vein is not very large, but it is always visible in B scan (Fig. 7.3). However, the calibres even of competent veins may differ widely. Some indication of normal vein size may be deduced from the subject’s body size and the diameter of the rest of his veins, for example, those visible on the back of the hand. On average, the diameter of the great saphenous vein in the saphenofemoral region in a healthy subject who has been standing for a few minutes is 7.5 mm (±1.8 mm), with a range of 3.5–11.0 mm (Mendoza et al. 2013). Fifteen centimetres below the saphenofemoral junction, it becomes smaller and more uniform in size. The great saphenous vein can be overlooked occasionally in a supine subject.

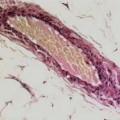

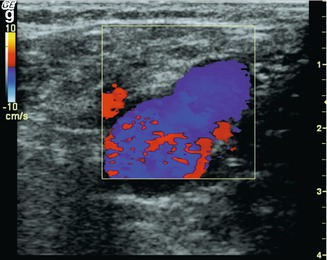

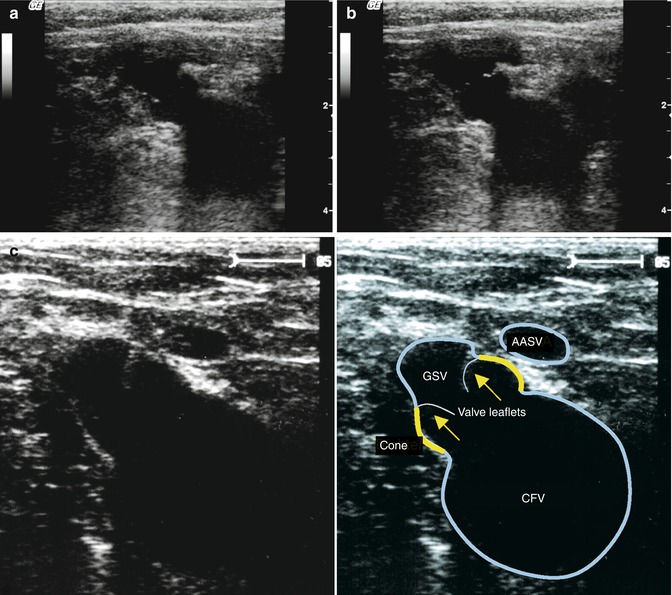

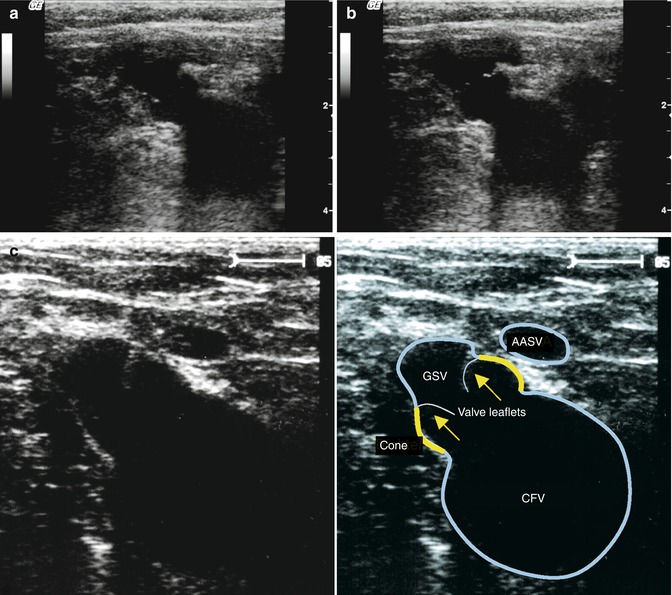

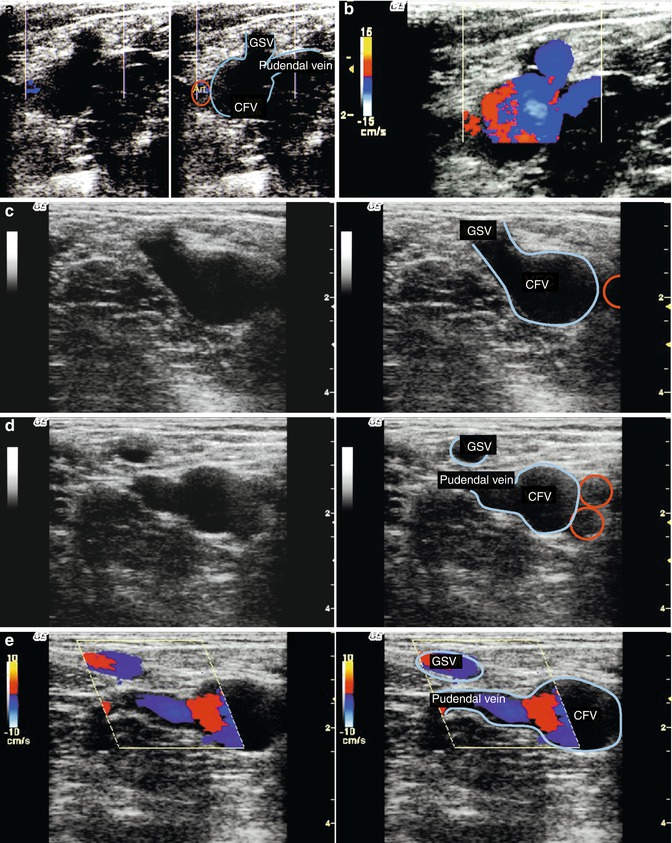

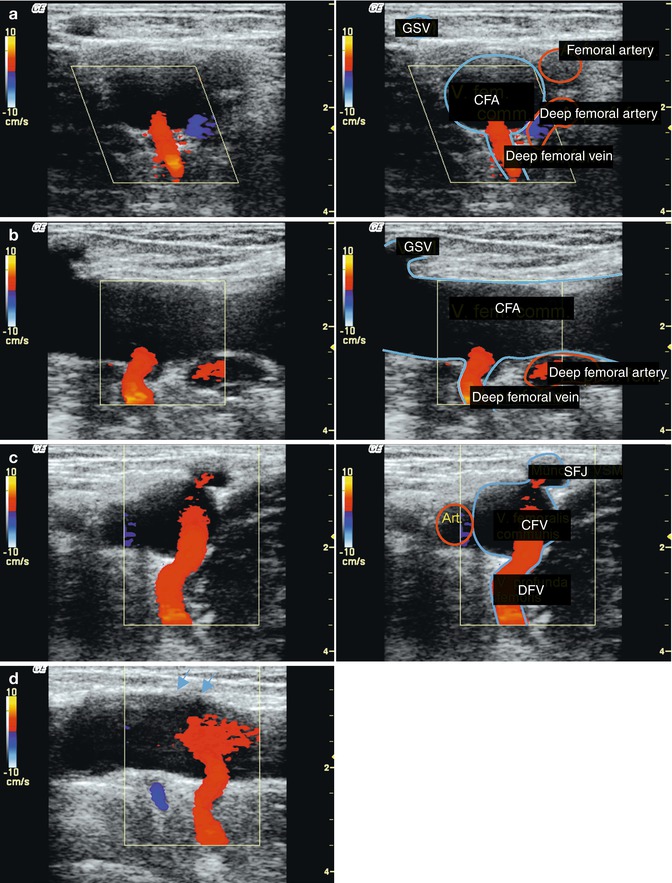

Fig. 7.3

Normal findings of the saphenofemoral junction. (a) B scan in transverse view through the left groin of a thin subject standing. Note that the entire venous network, including the common femoral vein is no more than 2 cm below the surface (scale on the right). The saphenofemoral junction is outlined and seen clearer on the moving image (online material). (b) Colour duplex ultrasound of the same subject during muscular systole demonstrating antegrade flow in the common femoral vein and saphenofemoral junction. (c) B scan of the same subject 1 cm further down where the saphenofemoral junction has separated into a small calibre great saphenous vein and anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV). (d) Transverse view through the right groin in a standing subject with small calibre veins. During muscular systole, the blue signal in all the superficial veins represents antegrade flow as they join into the saphenofemoral junction. In this subject the pudendal vein curves anteriorly into the back of the great saphenous vein. For this reason the direction of antegrade flow towards the confluence of superficial inguinal veins is towards the probe and therefore appears red. Investigating flow in muscular diastole is important for distinguishing between a normal finding and pathological reflux. If antegrade flow continues in the pudendal vein 1 s after the end of muscular systole, it is pathological. The mouth at the saphenofemoral junction is clearly visible (yellow arrows) (Art. common femoral artery). (e) Transverse view through the right groin with a common drainage of the great saphenous and anterior accessory saphenous veins into the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ). There is a separate drainage of the pudendal vein directly into the common femoral vein. The superficial external pudendal artery is visible crossing the saphenofemoral junction. This is a common finding (online material). (f) Transverse view through the right groin demonstrating a wide saphenofemoral junction in a big man. Despite its relatively large calibre, the junction was competent (SFA superficial femoral artery, DFA deep femoral artery, CFV common femoral vein). (g) Same position as in (f) with colour duplex in muscular systole and antegrade flow (blue). In diastole there was no reflux in the saphenous trunk or through the saphenofemoral junction

Copyright: [Author]

It is common to see the familiar image of a narrow calibre great saphenous vein terminating in a broad mouth at the saphenofemoral junction (Fig. 7.3d). Here the valve leaflets are frequently observed moving with changes in the blood flow (see also Figs. 7.6 and 7.7).

The anterior accessory saphenous vein joins the great saphenous vein from the side at an acute angle in the saphenofemoral region. In transverse view it is seen lateral to the great saphenous vein and vertically above the femoral vein (Fig. 7.3c–e). It is not always visible in B scan. A useful rule is if an imaginary line is drawn along a tangent to the medial edge of the common femoral vein, the great saphenous vein lies medial and the anterior accessory saphenous vein lies lateral (Fig. 7.4) (for anatomical variations, see also Sect. 7.3.2; for reflux in the anterior accessory saphenous vein Sect. 7.3.7; and for its anatomical course Sect. 10.4).

Fig. 7.4

Normal relations of the great saphenous and anterior accessory saphenous veins. This is a transverse view through the left groin of a standing subject slightly below the saphenofemoral junction. The anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) lies vertically above the femoral vein and the great saphenous vein lies medially (“alignment” sign)

Copyright: [Author]

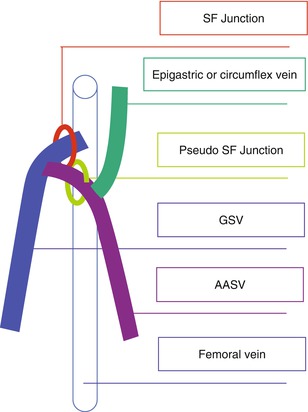

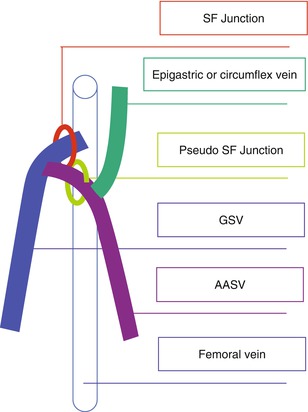

The superficial circumflex iliac vein may join either the great saphenous vein or the anterior accessory saphenous vein. It very rarely joins the common femoral vein directly. Using ultrasound it generally appears as a cranial extension of the great saphenous or the anterior accessory saphenous vein. Like the epigastric vein, it may consist of several branches which either unite or join the confluence separately. If one of these veins joins the anterior accessory saphenous vein from a cranial direction, then this junction may be mistaken for the saphenofemoral junction (Fig. 7.5). This mistaken identification is a source of error in surgery which may result in an inappropriate ligation (for reflux from these vessels, see also Sect. 7.3.5).

Fig. 7.5

Diagram of a “pseudo” saphenofemoral junction formed by the confluence of a lateral superficial inguinal tributary like the superficial circumflex iliac vein (SCIV) or epigastric vein (EV) and the anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) with the great saphenous vein (GSV) (green circle). The true saphenofemoral junction lies deeper (red circle)

Copyright: [Author]

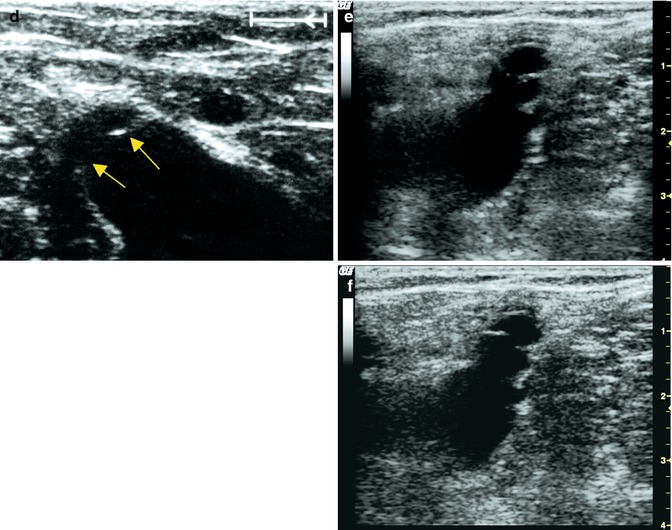

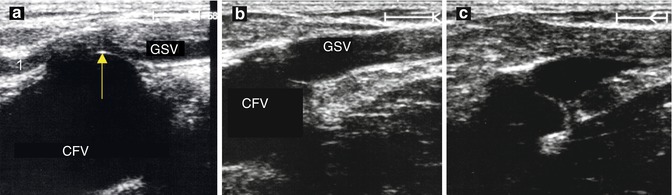

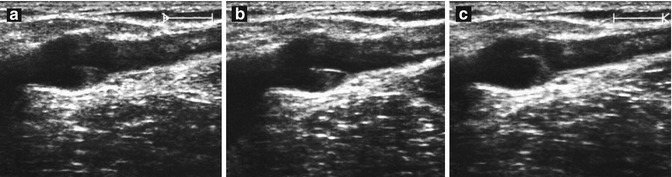

In B scan a valve cannot always be seen at the saphenofemoral junction. Although this is said to occur in up to 50 % of subjects, the use of more modern ultrasound machines has increased visualisation of the terminal valve to 91 %. In transverse view the valve leaflets can be seen moving during the various provocation manoeuvres (Fig. 7.6). In longitudinal view the valves can be seen in different positions. The terminal valve lies directly in the saphenofemoral region (Fig. 7.7a–c), and the preterminal valve lies below the confluence of superficial inguinal veins (Fig. 7.8), although the anterior accessory saphenous vein may also join distal to this valve. Valve movement can be detected in B scan. Rigid valve cusps indicate disease; however, flexible cusps do not exclude reflux. PW mode or colour duplex must be used to test for the presence of reflux.

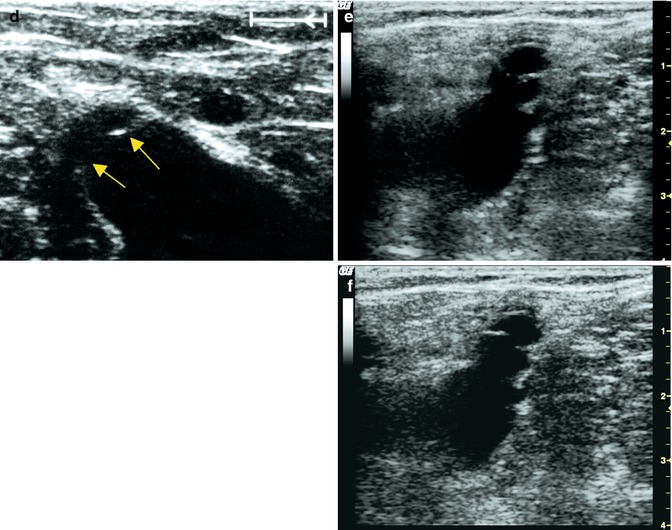

Fig. 7.6

Transverse image of the terminal valve at the saphenofemoral junction. (a) During muscular systole the valve leaflets are visible as white lines (arrow). (b) During muscular diastole the valve curves out towards the great saphenous vein when the junction is competent (muscular systole/diastole cycle on online material). (c) The valve (yellow arrows) opens during muscular systole causing movements in the mouth of the saphenofemoral junction (yellow contour). The anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) is also seen just before it terminates into the great saphenous vein (GSV). (d) Same groin in muscular diastole where the returning blood tries to re-enter the great saphenous vein. Here the valve leaflets (arrowed) are seen closing back towards the great saphenous vein. (e) Transverse view through the right groin this time with complete incompetence of the great saphenous vein. During muscular systole the valve cusps point towards the deep vein. (f) During muscular diastole in (e), the valves close back towards the great saphenous vein. It is impossible to establish whether reflux exists from the behaviour of the valves in a static B scan alone. In the film (online material), it is more obvious from the movement of the visualised blood that this valve is incompetent

Copyright: [Author]

Fig. 7.7

Longitudinal view through the saphenofemoral junction demonstrating a competent terminal valve. (a) Longitudinal view during a Valsalva manoeuvre causes the valve (arrowed) to curve out into the great saphenous vein (GSV). The epigastric vein is seen in the left of the image (1). (b) A valve leaflet is seen opening during muscular systole. (c) Same subject as in (b) demonstrating a closed valve leaflet curving into the great saphenous vein during a Valsalva manoeuvre (image of a rigid, inflexible valve is seen in Fig. 7.15)

Copyright: [Author]

Fig. 7.8

Longitudinal view through the great saphenous vein immediately below the saphenofemoral junction demonstrating the preterminal valve. (a) Both valve cusps are visible with the classical “swallow’s nest” shape. The valve is seen at rest in the standing subject. (b) The leaflet furthest from the surface is very clearly visible at rest. (c) The valve closes in muscular diastole

Copyright: [Author]

7.3.2 Anatomical Variations of the Saphenofemoral Junction

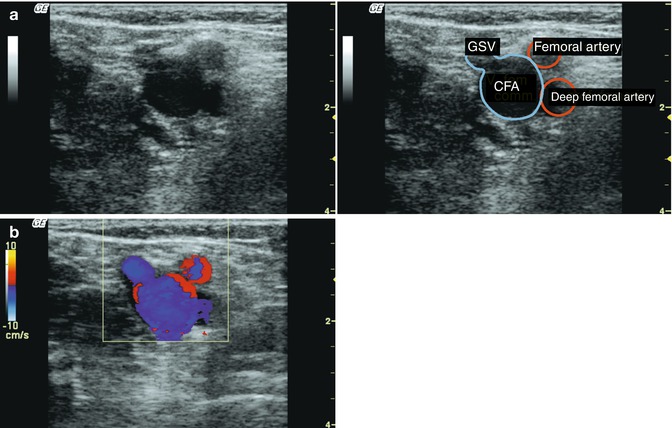

There are numerous anatomical variations at the saphenofemoral junction. For example, any or all of the superficial inguinal veins may join the common femoral vein directly. Direct drainage occurs frequently with the pudendal vein (Fig. 7.9). If this vein is overlooked during surgery, then it may be the source of a recurrence.

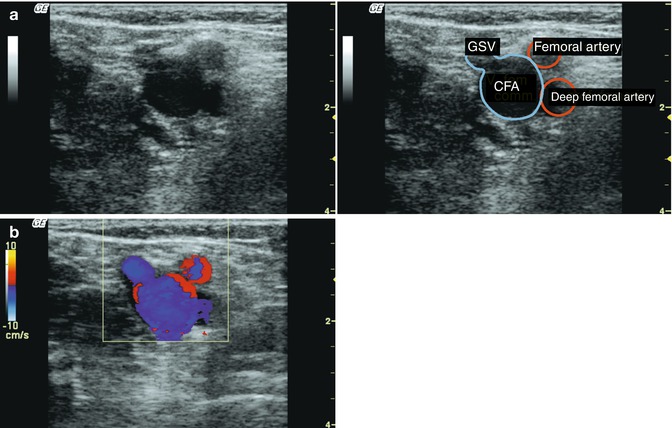

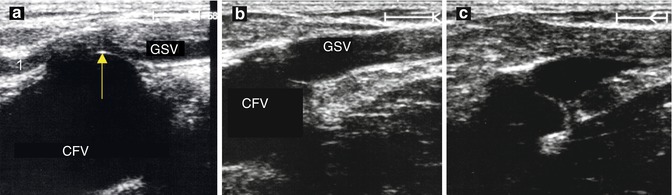

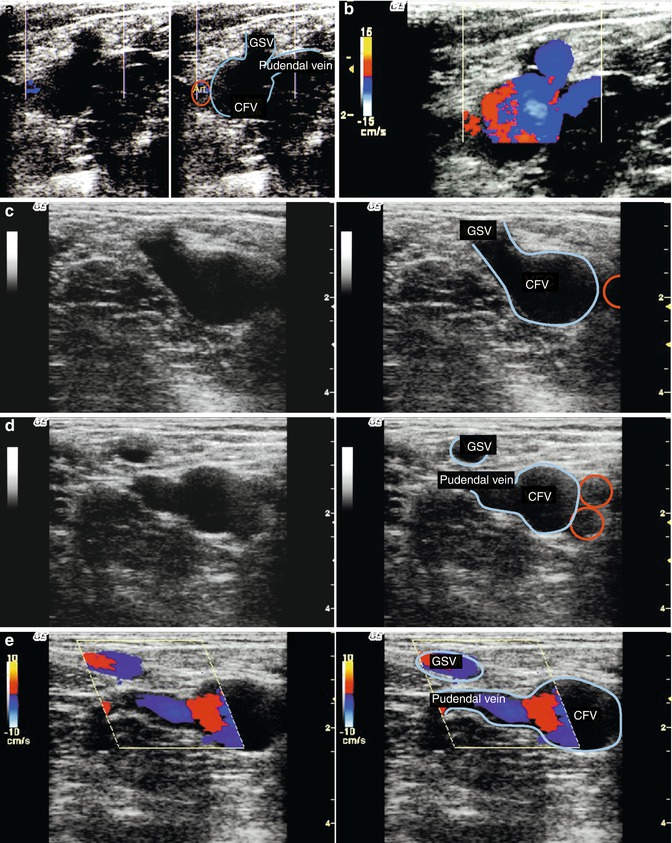

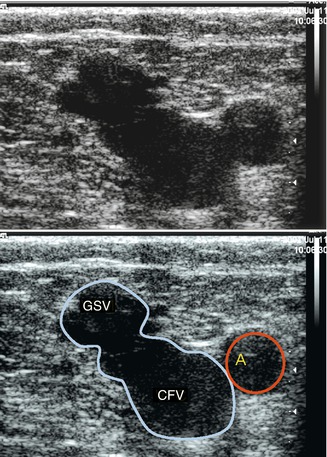

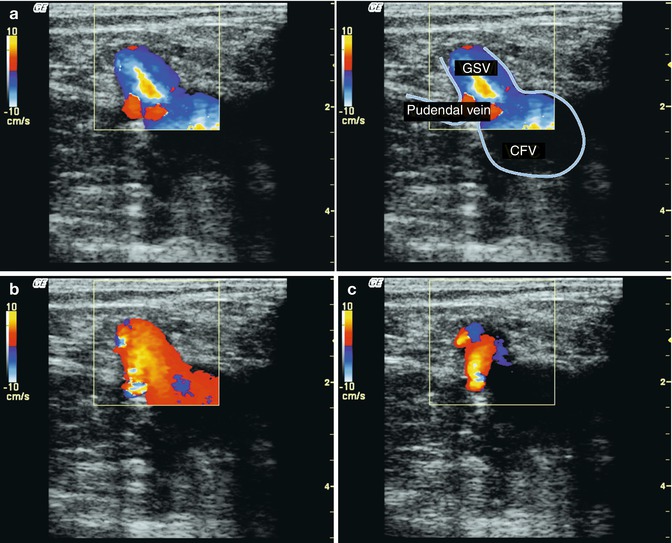

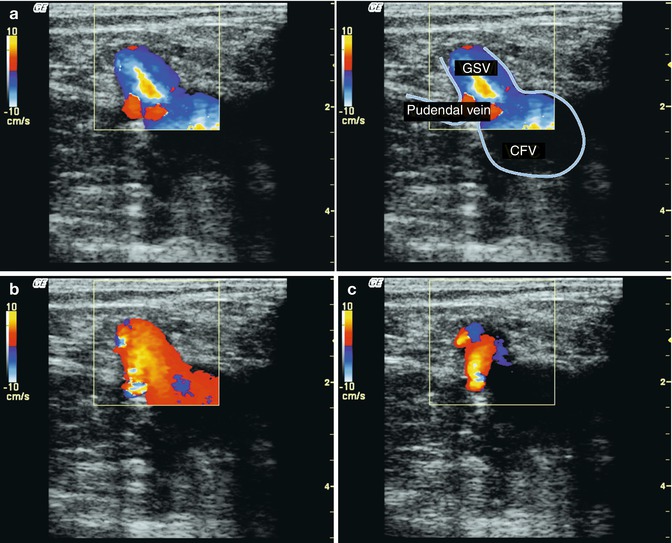

Fig. 7.9

Drainage of the pudendal vein directly into the common femoral vein. (a) Transverse view through the right groin. (b) Same position showing antegrade flow during muscular systole. (c) Transverse view through the left groin. The common femoral artery is circled (red). CFV common femoral vein, GSV great saphenous vein (online material). (d) Transverse view approx. 1 cm further distal. The great saphenous vein is visible as an independent vessel. The drainage of a very large pudendal vein is seen entering the common femoral vein directly (online material). (e) Same position with colour duplex with the probe tilted slightly so that both veins are visible in one image. At the end of muscular systole, there is a short flow reversal in the great saphenous vein (small red signal) until valve closure. However, long-lasting flow is now apparent in the pudendal vein. It is blue because the blood is refluxing away from the probe and pathological because the flow is prolonged and the pudendal vein is very dilated in comparison to the great saphenous vein (online material)

Copyright: [Author]

Duplication of the great saphenous vein at the saphenofemoral junction is very rare, even though this is postulated repeatedly as a cause of recurrence. According to Caggiati (personal communication), this variant does not occur. The great saphenous vein may join the common femoral vein directly at the groin or a few centimetres in either direction. Information on the level of the saphenofemoral junction is helpful to the surgeon but not as important as determining the level of the sapheno-popliteal junction.

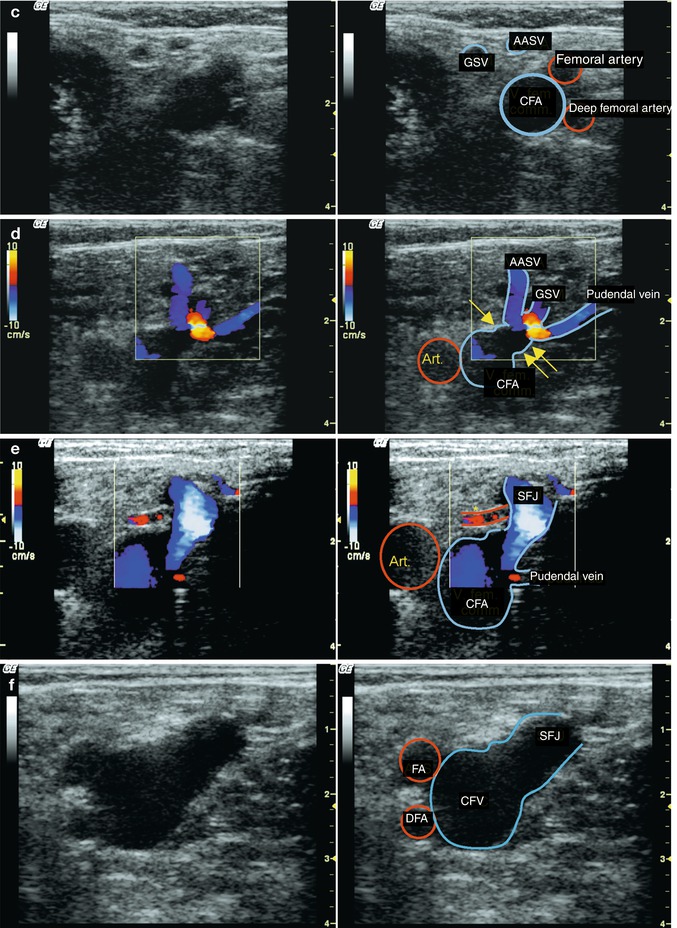

In the majority of cases, the anterior accessory saphenous vein terminates in the region of the saphenofemoral junction where it joins the great saphenous vein (Fig. 7.3). Sometimes it may join up to 5 cm further down. It occasionally joins the femoral vein directly immediately adjacent to the great saphenous vein (Fig. 7.10). Very rarely it may join the common femoral vein by passing between the superficial femoral artery and the deep femoral artery (Fig. 7.11). It is equally rare to find a duplication of the anterior accessory saphenous vein in the saphenofemoral region (Fig. 7.12). If these anatomical variations of the anterior accessory saphenous vein are missed preoperatively, they may provide a source of recurrence.

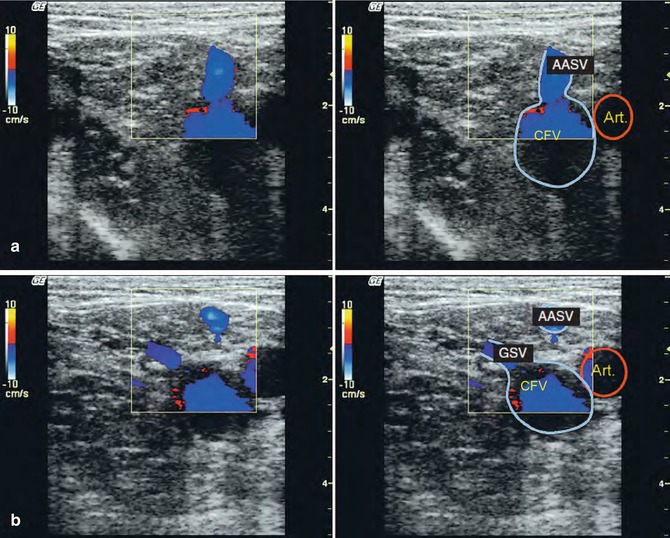

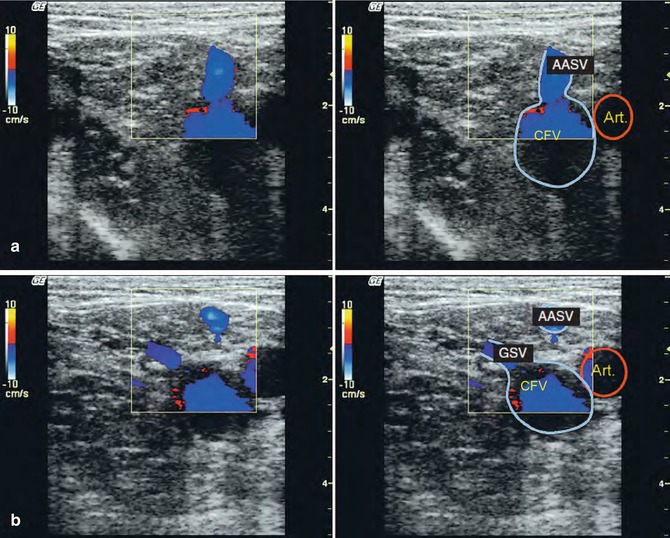

Fig. 7.10

Independent drainage of the anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) into the common femoral vein (CFV) (online material). (a) Transverse view through the left groin in a standing subject during muscular systole. There is antegrade flow up the anterior accessory saphenous vein and into the common femoral vein. (b) Transverse view 1 cm further distal from (a) demonstrating the great saphenous vein joining the common femoral vein. The anterior accessory saphenous vein is visible as an independent vessel lateral to the saphenofemoral junction

Copyright: [Author]

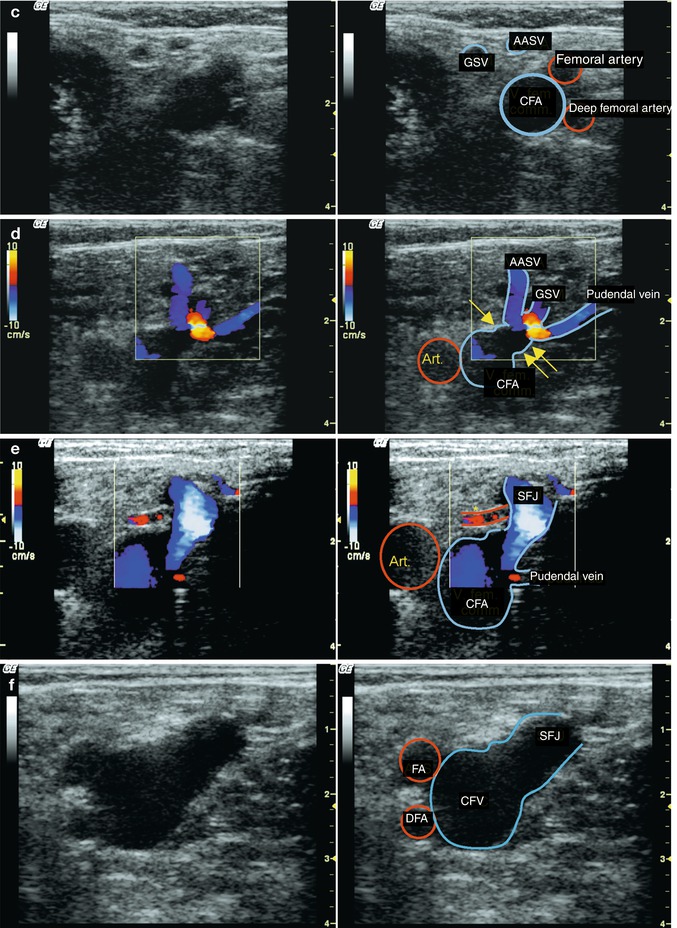

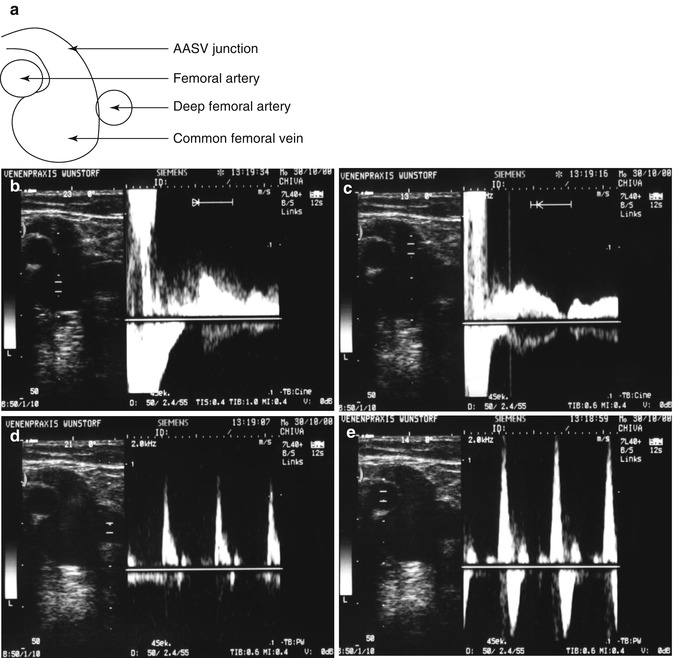

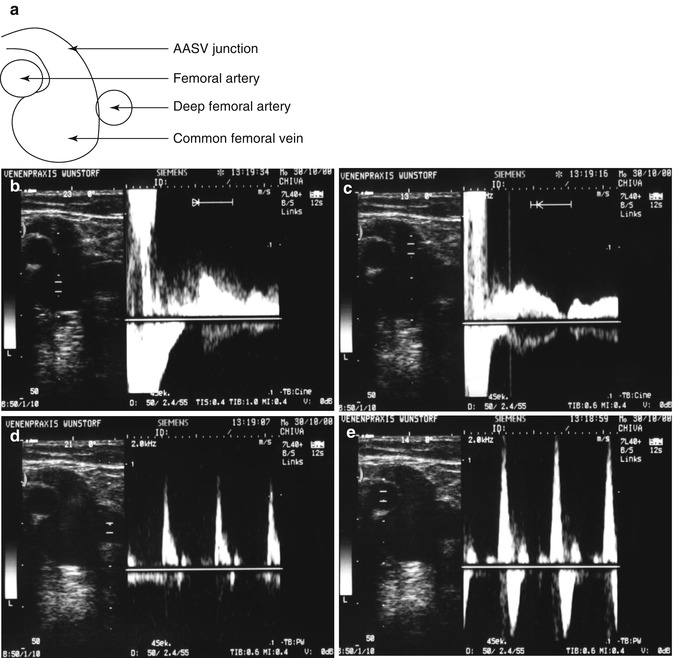

Fig. 7.11

Confluence of the anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) between the superficial and deep femoral arteries. (a) Diagram of the position of the arteries in relation to the confluence. (b) Measurement in the common femoral vein which is the reflux source. (c) Measurement in the confluence of the anterior accessory saphenous vein which is clearly refluxive. (d, e) Velocity profiles in the two adjacent arteries

Copyright: [Author]

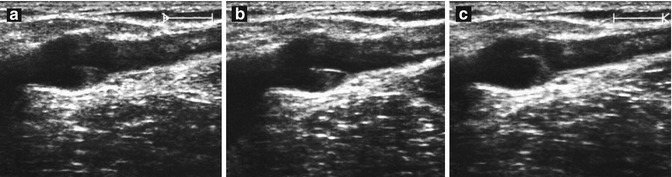

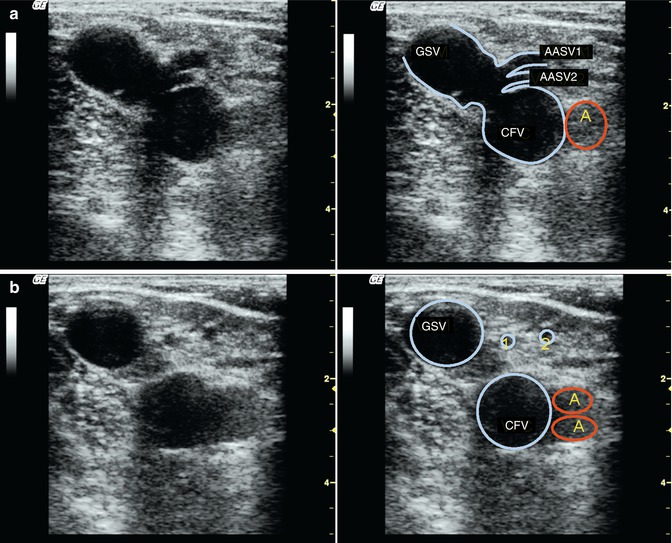

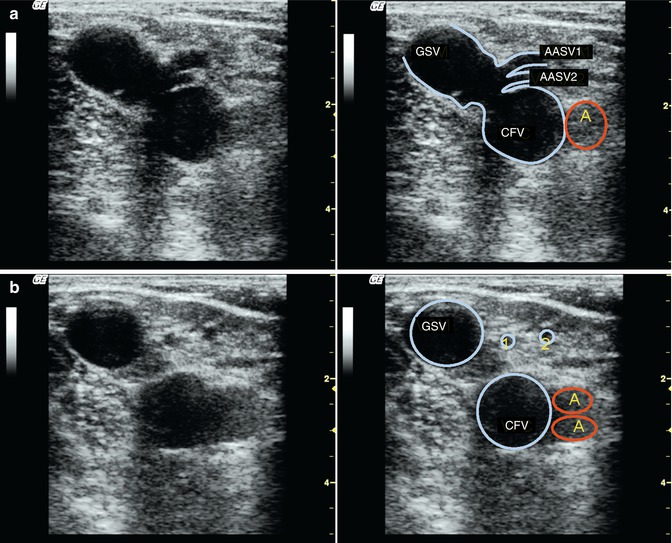

Fig. 7.12

Saphenofemoral junction. Transverse view through the left groin in a standing patient with an incompetent terminal valve and a dilated great saphenous vein (GSV) which turns left at the top of the image. Two competent anterior accessory saphenous veins (AASV) are seen draining separately into the saphenofemoral junction. (a) Region of the drainage points of both anterior accessory saphenous veins. (b) 1 cm further distal

Copyright: [Author]

In most cases the posterior accessory saphenous vein will not form part of the confluence of superficial inguinal veins but will meet the great saphenous vein in the upper thigh.

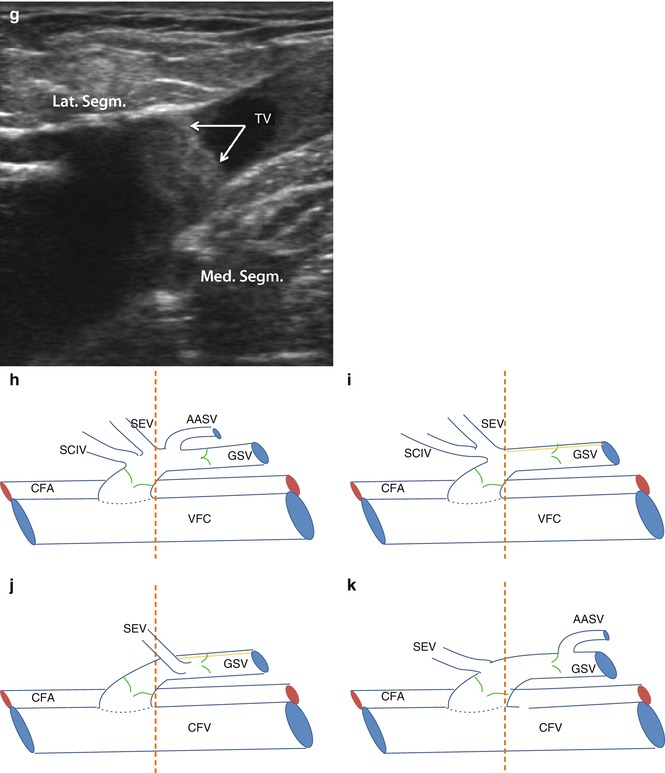

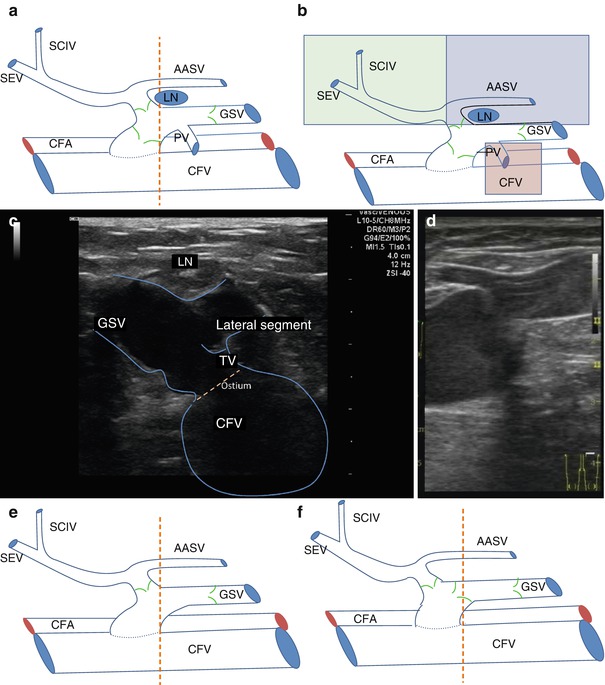

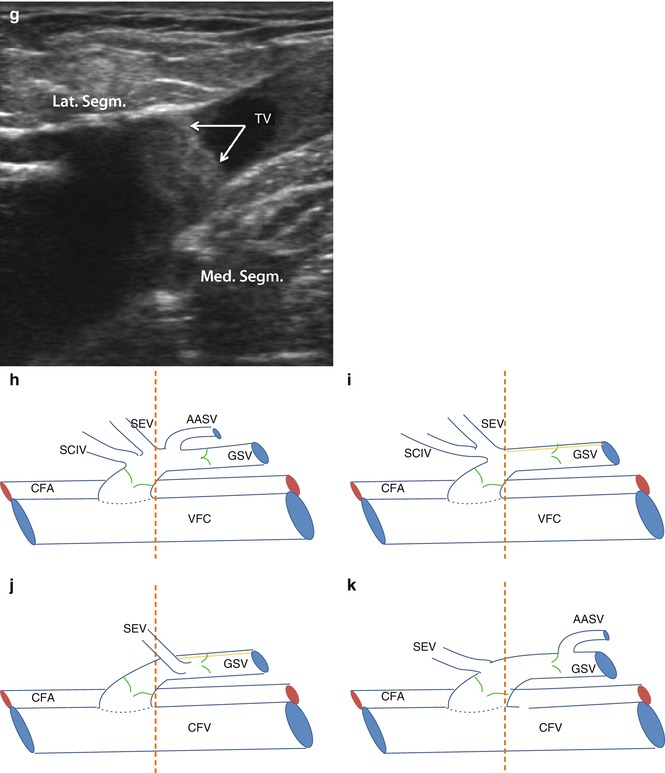

The tributaries join medially (pudendal vein and much further distal the posterior accessory saphenous vein) and laterally (epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac from cranial, anterior accessory saphenous vein from caudal). Hildebrandt’s diagram provides a simplified classification supplemented by additional information from Mühlberger (Fig. 7.13). Only the pudendal vein drains medially at the saphenofemoral region (Fig. 7.13a). There are laterally joining veins from cranial (epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac veins) and caudal (anterior accessory saphenous vein), which may join above the distal edge of the ostium (dotted line in Fig. 7.13a and fainter in the other images) or below this point. The level at which the anterior accessory saphenous vein joins may be important for positioning the fibre in endoluminal laser treatment. Furthermore, the presence and location of the terminal and preterminal valves should be defined if selective ablation techniques are performed. Some of the anatomical variations are given in Fig. 7.13.

Fig. 7.13

Junctional variations and valves for common or separate inflow from the proximal and lateral tributaries. (a) Standard saphenofemoral junction with tributaries. The pudendal vein is the single medial segment which joins between the terminal and preterminal valves. The lateral segment is shown with a common confluence of a cranial and caudal branch and another valve at the level of its junction with the great saphenous vein. The typical position of a lymph node (LN) lateral to the great saphenous vein is shown. The perpendicular dotted line marks the caudal edge of the ostium. (b) Additional information defining the lateral segment (light green/light purple) and the medial segment (light brown). The lateral segment is divided into cranial (green) and caudal (light purple) parts. (c) Transverse view of the lateral segment distal to the terminal valve (TV). An imaginary dotted line drawn around the front wall of the common femoral vein and passing through the confluence of the great saphenous vein will give the exact point where the great saphenous vein enters the femoral vein. This is known as the fossa ovalis or ostium. (d) Longitudinal view demonstrating the confluence of the lateral cranial segment also distal to the terminal valve. (e) Absent terminal valve. (f) Confluence of the lateral segment consisting of the superficial epigastric, circumflex iliac and anterior accessory saphenous veins. Note that here they are proximal to the terminal valve. (g) In this image the confluence of the lateral and medial segment are both proximal to the terminal valve. (h) All of the superficial inguinal tributaries join between the terminal and the preterminal valves. (i) The lateral cranial tributaries may join separately from one another or together as in this illustration between the terminal and preterminal valves. The anterior accessory saphenous vein is not present. (j) Isolated entry of the superficial epigastric vein (cranial lateral segment). (k) The anterior accessory saphenous vein enters just distal to the preterminal valve (CFA common femoral artery, LN lymph node, TV terminal valve, CIV circumflex iliac vein, SEV superficial epigastric vein, PV pudendal vein, AASV anterior accessory saphenous vein, GSV great saphenous vein) (Drawings Dr. Andreas Hildebrandt, Berlin; by kind permission)

Copyright: Dr. A. Hildebrandt, Berlin

Precise documentation of the saphenofemoral junction should include all the superficial inguinal veins and their relationship and distance from the terminal and preterminal valves. Such information is needed principally for study purposes, but in the context of new treatments which selectively preserve tributaries, pre-procedural documentation may become important.

7.3.3 Reflux from the Common Femoral Vein

The most common source of reflux in the great saphenous vein is the saphenofemoral junction. Here the saphenous trunk is filled refluxively from the common femoral vein. During the Valsalva manoeuvre or muscular diastole, blood flows down from the iliofemoral veins into the great saphenous vein. This can be seen indirectly in B scan from the behaviour of the valves and the dilation of the vein wall during refluxive flow.

The mouth of the great saphenous vein generally appears dilated in B scan (Fig. 7.14). The calibre of the great saphenous vein often increases after the subject has been standing for a few minutes. However, reflux may also occur across the saphenofemoral junction even if the vein is not dilated.

Fig. 7.14

Incompetent saphenofemoral junction of the left leg in B scan. The diameter of the great saphenous vein (GSV) is grossly dilated (c.f. Fig. 7.3) (A common femoral artery, VFC common femoral vein)

Copyright: [Author]

Much information can be gained in B scan:

The morphology of the saphenofemoral junction and the proximal great saphenous vein

The morphology of the confluence of superficial inguinal veins

The presence or absence of thrombus in the common femoral or great saphenous veins (compression manoeuvre, Chaps. 11 and 14)

Morphology of the valves

Drainage paths of the insonated veins

7.3.3.1 Morphology of the Saphenofemoral Junction and the Confluence of the Superficial Inguinal Veins

The following questions should be answered:

Do the superficial inguinal veins join the femoral vein directly or via the great saphenous vein?

Which superficial inguinal tributaries are present?

Is the saphenofemoral junction dilated?

Is there an aneurysm?

Aneurysms of the saphenofemoral region should be identified because of the potential difficulty in surgical treatment. They may be either discrete or fusiform dilatations of the great saphenous vein itself (Fig. 7.15) or dilatations growing out of the vein wall (Fig. 7.16). Surgery on the saphenofemoral junction may be complicated by these thin-walled balloons of blood. They may grow as large as a golf ball and obscure the operating field. Tributaries often flow directly into these aneurysms (Fig. 7.17).

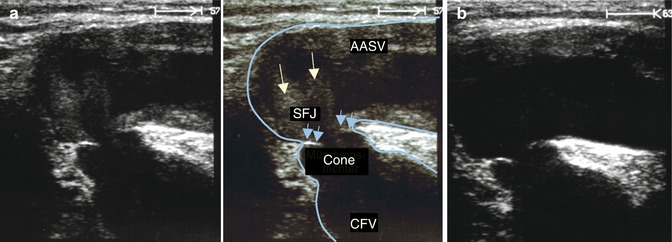

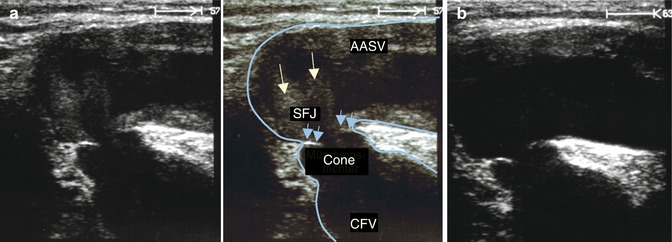

Fig. 7.15

Aneurysm at the confluence of the great saphenous vein and the anterior accessory saphenous vein (AAVS) with incompetence of the terminal valve and a competent preterminal valve (complete, Hach Class I). (a) Transverse view through the left groin demonstrating the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) during muscular diastole. Blood refluxes from the common femoral vein through the incompetent terminal valve into the great saphenous vein and directly into the laterally positioned anterior accessory saphenous vein. Turbulence can be observed in the aneurysm (white arrows). Although this is during diastole and there is reflux, the valve cusp point towards each other They are not curved back into the great saphenous vein as would be expected with reflux but are rigid (blue arrows) (CFV common femoral vein). (b) Same position after the end of diastole. The erythrocyte sludge has gone, and the valve cusps remain rigid in the same position as during diastole. The narrow lumen between the rigid valve cusps caused a jet-effect which may have led to the development of the aneurysm (online material)

Copyright: [Author]

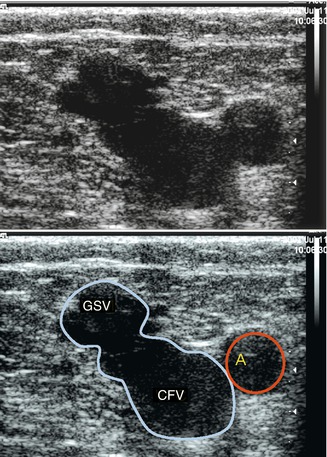

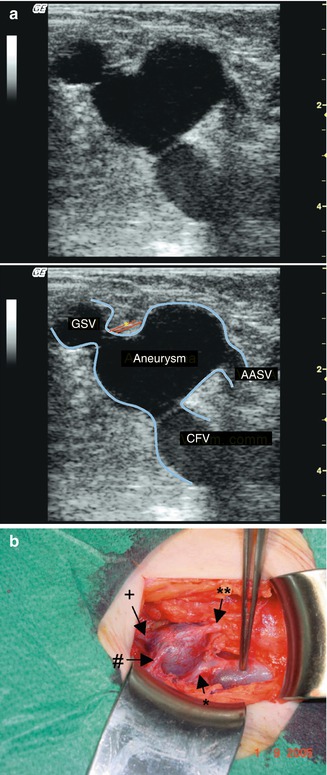

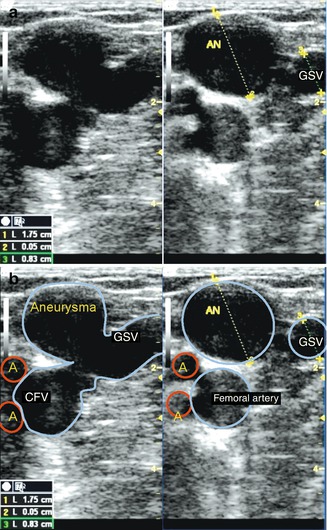

Fig. 7.16

Aneurysm formed by a bulge in the side wall of the vein. (a) Transverse view through the right groin with an incompetent saphenofemoral junction. The aneurysm looks like a mushroom growing out of the great saphenous vein (GSV). (b) 1 cm further distal the aneurysm (AN) and the great saphenous vein look like two different vessels

Copyright: [Author]

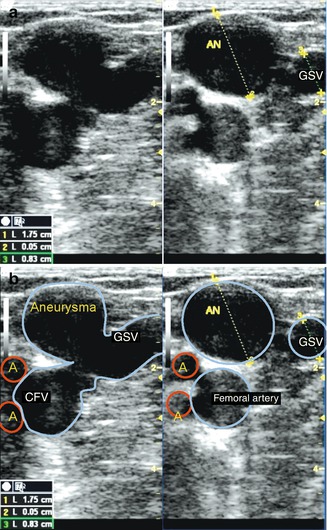

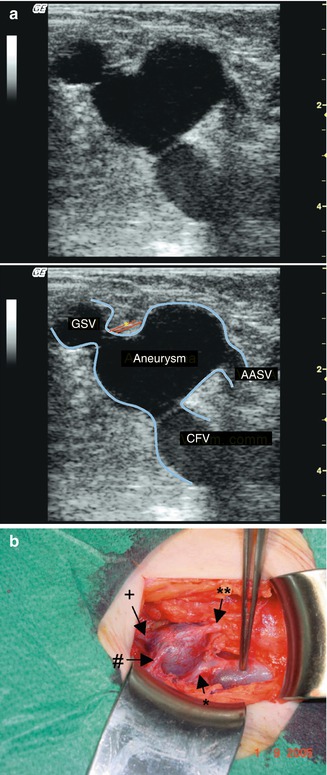

Fig. 7.17

Side aneurysm of the great saphenous vein (GSV) at the saphenofemoral junction. (a) Transverse view through the left groin in B scan. The anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) is seen draining into the aneurysm. The superficial external pudendal artery crosses between the aneurysm and the great saphenous vein (online material). (b) Intraoperative photograph of the aneurysm exposed showing its connections with the pudendal (#) and epigastric (+) veins. The forceps are pointing to the normal calibre great saphenous vein just below the band-like superficial external pudendal artery (** anterior accessory saphenous vein)

Copyright: [Author]

Turbulence is normally observed in aneurysms in B scan during provocation manoeuvres. A thrombus in the lumen of an aneurysm is rare (Pascarella et al. 2005). Surprisingly, in contrast to the arterial circulation, there is no relationship between the presence of an aneurysm and the development of a superficial vein thrombosis (Kalodiki et al. 2012). A combination of a weak vein wall and an overload of refluxive blood volume striking the vein wall may encourage aneurysm formation. The resulting flow characteristics seem to prevent thrombus formation.

Even with incompetence the terminal valve is usually seen fluttering. It folds into the great saphenous vein during muscular diastole if reflux is present, or during a Valsalva manoeuvre. If the valve is rigid and immobile, this may suggest a primary valve defect or post-thrombotic scarring (Fig. 7.15).

If the system is poorly drained (Sect. 3.2.3), echoes appear in B scan inside the great saphenous vein immediately after a provocation manoeuvre. These may make the vein appear homogeneous with a similar echogenicity as the surrounding tissue. This depends on the accumulation of erythrocytes and the formation of so-called erythrocyte sludge. If the vein appears heterogeneous, this may indicate turbulence and varying flow velocities (Fig. 7.15). Patients presenting with this turbulence may go on to develop an aneurysm at the saphenofemoral region.

The direction of blood flow can be seen in B scan from the erythrocyte sludge. However, reflux can be seen much more clearly using colour duplex ultrasound. This allows us to answer the following questions:

Does the reflux flow from the common femoral vein through the saphenofemoral junction into the superficial veins?

Does it fill the great saphenous vein, anterior accessory saphenous vein or both refluxively?

Is any other superficial inguinal tributary also refluxive?

Is isolated reflux present in a named superficial inguinal tributary?

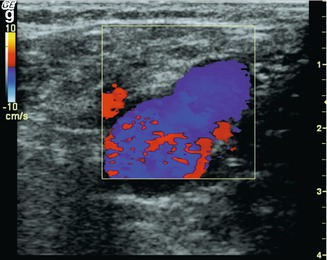

Reflux from the common femoral vein through the saphenofemoral junction via an incompetent terminal valve is measurable at the saphenofemoral region (Fig. 7.18). This is termed complete incompetence of the great saphenous vein. This finding must be distinguished from the tributary type incomplete incompetence. In this situation the reflux arises from the deep leg veins via an incompetent superficial inguinal tributary. The terminal valve remains competent (Sects. 7.3.4 and 7.3.5).

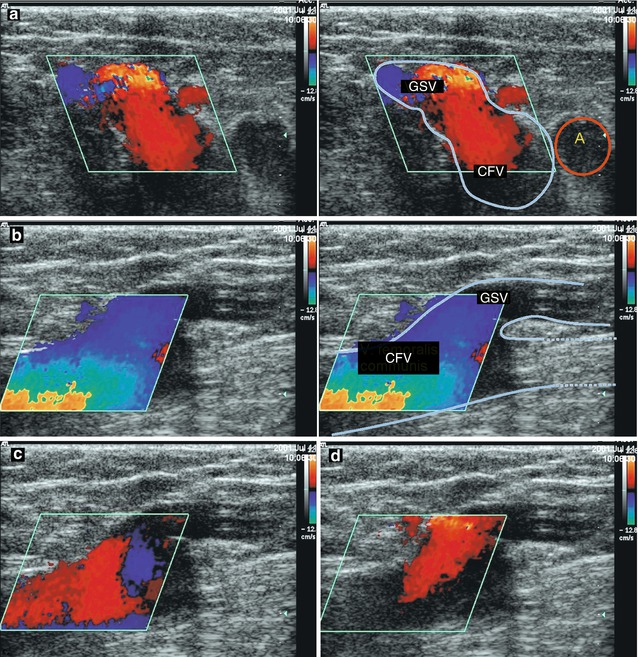

Fig. 7.18

Incompetent saphenofemoral junction in colour duplex in the patient from Fig. 7.13a). (a) Transverse view through the groin during muscular diastole demonstrating reflux from the common femoral vein (CFV). The blood flows from the deep vein towards the probe (red). Note that the common femoral vein and saphenofemoral junction are both coloured red. (b) Longitudinal view through the junction in the same patient during muscular systole. The blood flow is antegrade in both the deep and superficial veins. (c) Same longitudinal position at the very beginning of muscular diastole. The blood starts to change direction and flows out of the common femoral vein. (d) During muscular diastole the blood flows out of the common femoral vein and into the great saphenous vein. Only with this unequivocal finding is it correct to speak of incompetence of the saphenofemoral junction

Copyright: [Author]

In addition to the reflux from the common femoral vein, it is not uncommon to find a tributary (usually the pudendal vein) which is also refluxive or at least dilated (Fig. 7.19). Antegrade flow will be found in both these veins during muscular systole. The course of the pudendal vein to its termination in the saphenofemoral region may show red representing flow towards the probe. In diastole it is important to clarify whether flow can be observed from the deep vein into the great saphenous vein (red) and whether the pudendal vein presents a long-lasting flow. The colour red or blue depends on the course of the pudendal vein towards the probe. However, it is pathological if this flow is prolonged in diastole. Here it may fill the great saphenous vein refluxively or drain into the common femoral vein through the saphenofemoral junction (Sect. 7.3.6).

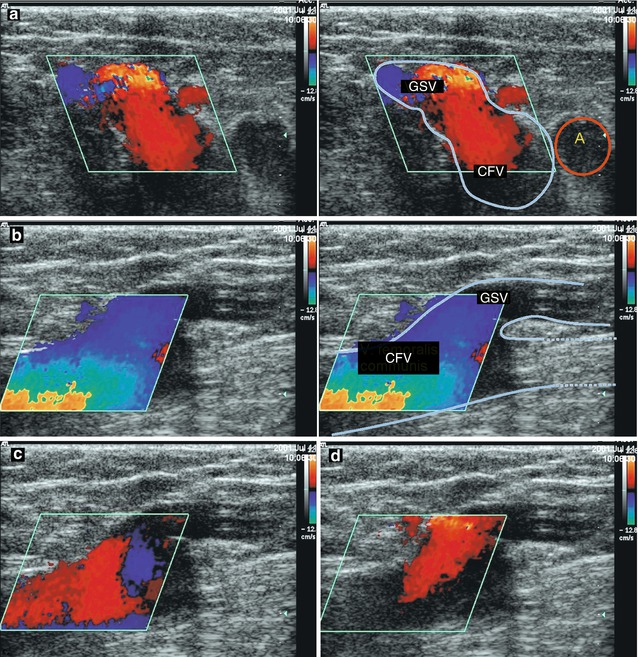

Fig. 7.19

Incompetent saphenofemoral junction with a refluxive pudendal vein (online material). (a) Transverse view through the left groin during muscular systole demonstrating antegrade flow in both veins (great saphenous and pudendal). In the pudendal vein antegrade flow towards the probe (red), flow is only visible at the confluence with the great saphenous vein (GSV). (b) At the beginning of muscular diastole, there is clear reflux from the common femoral vein through the saphenofemoral junction. The reflux from the pudendal vein cannot be evaluated at this early timepoint. (c) Towards the end of muscular diastole, it becomes clear that in addition to reflux from the common femoral vein (CFV), the great saphenous vein is also filled refluxively by the pudendal vein

Copyright: [Author]

Sometimes the findings at the saphenofemoral junction are contradictory. It may be competent during the Valsalva manoeuvre and incompetent with another provocation manoeuvre, or vice versa. Occasionally it is incompetent and then competent consecutively using the same manoeuvre twice. When this happens the veins are not usually very dilated. The contradiction may result from the different intensities of the manoeuvres. The calf compression applied or the effort in raising the toes may not have been the same both times. The frequency of the challenge test is also important because this affects the volume of blood which collects in the leg prior to the subsequent manoeuvre. Poorly drained systems may likewise give contradictory results (Sect. 3.2.3). In the latter case, an elevation-dependency manoeuvre may clarify what is happening (Sect. 6.9). As the patient stands up from a period of leg elevation, a long-lasting reflux will be observed in the vein if it is pathological (Lattimer et al. 2013). Competent valves may be found in the common femoral vein which may result in a negative Valsalva reflux but a positive reflux following a calf compression or contraction manoeuvre (Lattimer et al. 2012b). If the contradiction cannot be resolved, then the subject must be called in again for more testing. However, this problem only arises in borderline cases of pathology and in the early stages of incompetence where treatment is rarely required.

The deep femoral vein joins the femoral vein from posterior in the proximal thigh to form the common femoral vein. Normally this confluence cannot be seen during the examination of the saphenofemoral junction. The deep femoral vein may join at an acute angle in which case it will be the same colour (blue) on duplex as the femoral vein. Sometimes a red jet can be seen entering the common femoral vein from posterior (Fig. 7.20a, b). This means that the deep femoral vein joins at right angles. This finding is not pathological.

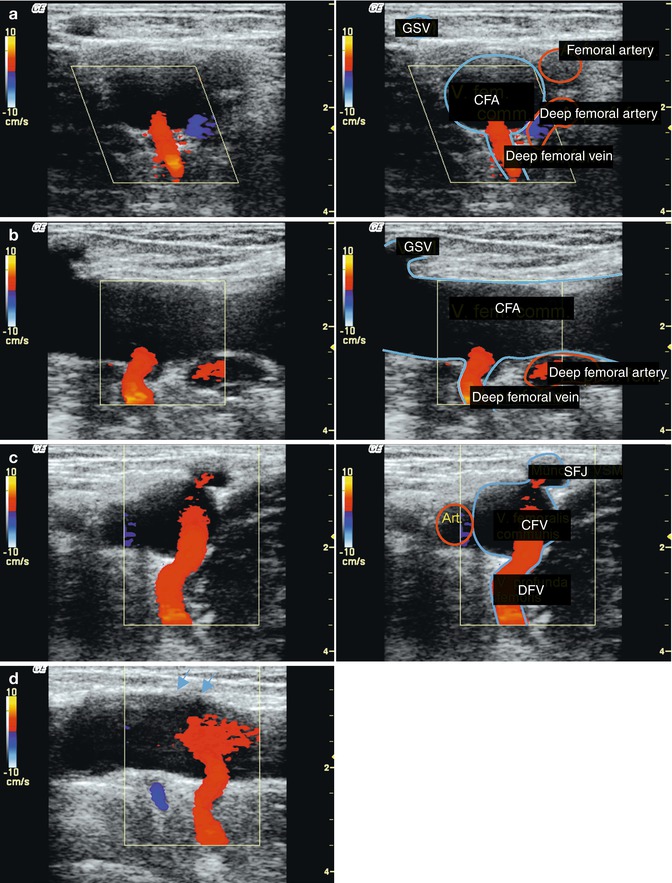

Fig. 7.20

Confluence of the deep femoral vein in the groin. (a) Transverse view of the left groin showing the common femoral (CFV), deep femoral (DFV) and great saphenous veins (GSV). The deep femoral vein joins below the saphenofemoral junction. Therefore, the great saphenous vein appears separate from the common femoral vein (online material). (b) Longitudinal view in the same subject. (c) Transverse view of the right groin showing the common femoral, deep femoral and great saphenous veins. The deep femoral vein joins immediately opposite the great saphenous vein. It looks as if the deep femoral vein fills the great saphenous vein refluxively (red) because the flow is towards the probe. (d) Longitudinal view in the same subject. The saphenofemoral junction is indicated opposite the confluence of the deep femoral vein (blue arrows)

Copyright: [Author]

A special situation occurs when there is reflux arising from the deep femoral vein which flows directly into the great saphenous vein (Fig. 7.20c, d

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree