Fig. 21.1

Subserosal fibroid. Transvaginal grayscale transverse image of the uterus demonstrates a round heterogeneous mass, measuring 0.51 cm wide (+), projecting beyond the contour of the uterus. The gestational sac with embryo is noted

Fibroids are highly sensitive to estrogen, which can promote their growth and maturation in the first trimester. They may even grow so large as to overwhelm their blood supply, resulting in painful degenerative changes including changing echogenicity and loss of clear circumferential vascularity. The loss of blood supply may result in various types of degeneration: hyaline or myxoid degeneration, calcification, cystic degeneration, or red (hemorrhagic) degeneration. Red, or carneous, degeneration is a hemorrhagic infarction secondary to venous thrombosis within the periphery of the tumor or rupture of intratumoral arteries. It is of upmost importance to utilize sonography early in pregnancy to identify those fibroids that would be clinically significant due to their size and location. Submucosal fibroids may increase the risk of early pregnancy loss. If first-trimester miscarriage is eluded, these benign masses can have significant detrimental ramifications that are not realized until later trimesters. Mass effect and disruption of placental implantation caused by large fibroids compete with fetal growth and can obstruct fetal and placental delivery if located within the lower uterine segment [5, 9]. Increased pressure above a low-lying fibroid during labor increases the risk of uterine rupture and fetal mortality. Despite these complications, intervention is usually not necessary or commonly pursued until the postpartum period.

The pervasive fibroid can present unexpected challenges for the medical imaging specialist. Subserosal-type fibroids pushed close to an ovary by the gravid uterus can be difficult to differentiate from a solid ovarian mass. Degenerative changes in such a fibroid may further complicate diagnosis. Imaging a separate ovary, often better differentiated on three-dimensional sonography, will exclude an ovarian mass. Color Doppler may also be helpful in delineating blood flow that connects the uterus and fibroid. If ultrasound is inconclusive, further imaging with MRI may be required.

Adnexal Masses

Traditional management of adnexal masses during pregnancy has been surgical, but with surgeries come both fetal and maternal risks. The goal of ultrasound evaluation is to determine when conservative management with observation is appropriate. Simple cysts of any size and classic-appearing hemorrhagic cysts are highly unlikely to be malignant lesions in menstruating females. Follow-up or further evaluation is recommended only when the size is greater than 5 cm. Reports have shown a high accuracy of ultrasound for determination of malignant potential. Schmeler et al. and Kumari et al. reported correct diagnosis of malignancy in all pregnant patients studied presenting with incidental adnexal masses [6, 10].

Corpus Luteum

A retrospective review of sonography performed on over 18,000 pregnant patients identified a 2.3 % prevalence of adnexal masses; the majority were small (<5 cm) simple cysts that were without complication during the pregnancies [11]. The majority of these cysts likely begin as corpora lutea: the most commonly encountered cystic adnexal mass during pregnancy [4]. Corpora lutea form after fertilization of an expulsed ovum from an ovarian follicle. They endure to produce progesterone and maintain the early pregnancy. Fluid-filled with smooth, thick walls, they grow to a maximum diameter at the end of the first trimester. The decreasing functionality of the corpus luteum as the placenta assumes that an endocrinologic role is reflected sonographically by its serially shrinking size by the second trimester.

The lifetime of the corpus luteum in a pregnant woman is much longer than during a normal menstrual cycle and it has more opportunity to grow; thus, complications such as rupture, torsion, and hemorrhage can more commonly occur in a pregnant patient (Fig. 21.2a, b) However, intervention and further imaging are otherwise unnecessary for this physiologic incidental finding and should not be pursued during the first trimester when progesterone production is essential.

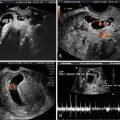

Fig. 21.2

Corpus luteum. Grayscale transvaginal (a) transverse and (b) sagittal images of the ovary demonstrate a predominately anechoic cyst containing hypoechoic dependent debris representing old blood products

Corpus Luteum Cysts

A persistent corpus luteum can seal externally within the ovary and continue to collect fluid within, forming a unilocular corpus luteum cyst. Because the cyst contains fluid, it is anechoic with enhanced through-transmission, though it may exhibit thin lacelike echogenic septae if it persists into the second trimester and is filled with blood [5]. The size of the cyst is a strong predictor of its ability to spontaneously regress, with almost all cysts under 5 cm in diameter resolving completely without intervention [12]. The most recent guidelines (2010) for non-gravid women from the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound do not recommend follow-up sonography for simple cysts smaller than 5 cm, whereas yearly sonography of larger cysts should be considered, despite low malignant potential [13]. Standard scheduling of obstetric ultrasounds offers the opportunity to track the growth of corpus luteum cysts throughout pregnancy.

Both the corpus luteum and corpus luteum cyst have distinguishing dense peripheral “ring of fire” vascularity on color Doppler imaging (Fig. 21.3a–c). These vessels exhibit low resistance and high diastolic flow on spectral Doppler. There are typically little or no internal solid components. Ectopic or heterotopic pregnancies in the adnexa imitate corpus luteum cysts because they, too, are fed by a peripheral ring of vessels and can be seen directly adjacent to a cyst (Fig. 21.4a, b). The critical distinction is made by determining if the adnexal mass is para- or intra-ovarian. Ectopic pregnancies should move independently from the ovary with pressure applied by the examiner. This “sliding sign” is not visualized during examination of intra-ovarian corpus luteum cysts, which remain coordinated in movement with the ovary. In a retrospective study of 78 pelvic sonograms performed on women exhibiting symptoms consistent with ectopic pregnancy during the first trimester, the radiologists were able to correctly identify ectopics in 23 of 27 patients exhibiting the “sliding organ sign.” Although not a strong differentiator, ectopic pregnancies also tend to be more complex and echogenic than luteal cysts when compared to the ovarian parenchyma [14].

Fig. 21.3

Corpus luteum cyst of pregnancy. Transvaginal (a) sagittal and (b) transverse grayscale images of the ovary demonstrate an anechoic round structure with thin walls. (c) Sagittal color Doppler image demonstrates peripheral vascularity representing the “ring of fire”

Fig. 21.4

Ectopic pregnancy. (a) Transverse view of the left adnexa depicting a thick, echogenic ring and (b) peripheral vascularity on sagittal color Doppler

Corpus luteum cysts are usually asymptomatic, especially when they are relatively small in size, as opposed to ectopic pregnancies that will invariably become symptomatic. However, large cysts can rupture, undergo torsion, and bleed [12]. Intervention is imperative for ectopic pregnancies and recommended for cysts and benign masses greater than 7 cm, but not recommended for small luteal cysts [13].

Hemorrhagic Corpus Luteum Cysts

The clinical presentation of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst is characterized by more unilateral pain than its predecessors. The resolution of pain does not correlate with resolution of the hemorrhagic cyst, which can evolve over subsequent months [15]. Sonographically, the acute phase of the hemorrhage demonstrates very hyperechoic internal echoes (Fig. 21.5a, b). As the blood settles, the cyst appears more heterogeneous with thin, fibrinous septations that are without color Doppler flow. The clot retracts to the walls of the cyst, appearing as a solid or reticular hyperechoic structure. Throughout this course, the cyst should always remain well defined with enhanced through-transmission owing to the predominant presence of non-bloody cystic fluid. If the cyst is not intact and the patient is symptomatic, a diagnosis of rupture is supported by the presence of free pelvic fluid.

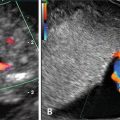

Fig. 21.5

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst of pregnancy. Grayscale transvaginal (a) transverse and (b) sagittal images of the ovary show heterogeneous echogenic material within an anechoic cyst representing hemorrhagic blood products in a corpus luteum cyst

Due to the lack of specificity observed in some hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts, follow-up imaging may be appropriate. Growth requires continued surveillance. The presence of thick septations and nodular walls, especially when there is associated vascularity, is suspicious for neoplasia and surgical intervention must be considered. Alternatively, magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful for further characterization (Fig. 21.6a–c). By the second-trimester anatomy scan, true functional hemorrhagic cysts should have involuted.

Fig. 21.6

Borderline mucinous tumor of the ovary. Transabdominal grayscale (a) sagittal and (b) transverse images of the ovary demonstrate a predominately cystic mass with thick septations. (c) Color Doppler imaging demonstrates blood flow within a septation

Decidualized Endometriomas

Sonography has both high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for endometriomas, most commonly implanted within the ovaries. These round, hypoechoic cystic masses have a characteristic sonographic appearance with regular thick walls and possibly small echogenic foci along the inner rim. Within the endometrioma, homogenous low-level echoes can resemble a hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst; however, the latter will involute by the second trimester and the former will not (Fig. 21.7). Just as the endometrium of the uterus decidualizes under the influence of progesterone during pregnancy, about 12 % of ovarian endometriomas also undergo decidualization [16]. Their benign appearance transforms to closely mimic borderline ovarian tumors (Fig. 21.8a, b). They can rapidly develop solid intracystic papillary excrescences and irregular walls. The projections may be quite vascular and can exhibit low resistance flow. Because ovarian endometriomas are more likely to undergo malignant transformation than extragonadal types, though uncommon in reproductive-age women with small endometriomas, the correct diagnosis is crucial and particularly complicated during pregnancy.

Fig. 21.7

Endometrioma. Transvaginal coronal image of the right adnexa demonstrates a large, thick-walled hypoechoic mass with homogeneous internal echoes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree