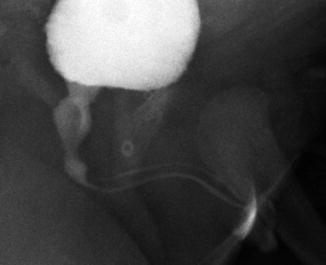

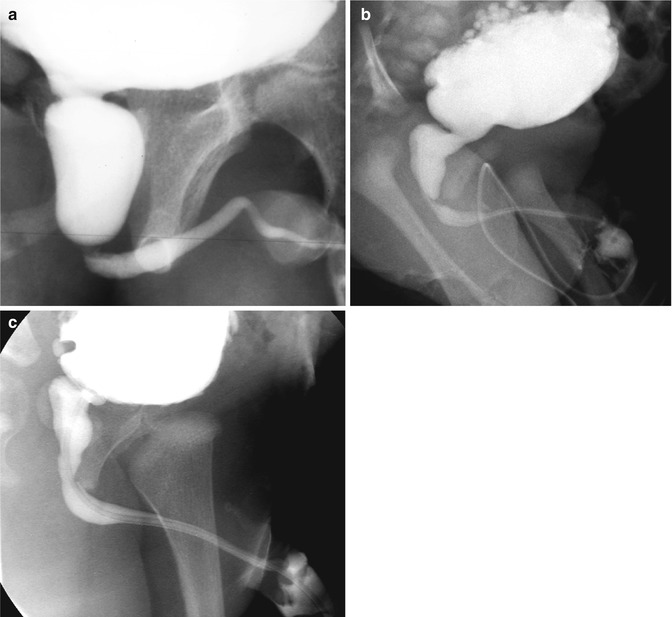

Fig. 15.1

(a) Normal male VCUG. A prostatic urethra; B membranous urethra; C pendulous urethra; D penile urethra. (b) Normal female urethra on VCUG. (c) Normal male RUG

The male urethra is composed of an anterior segment and a posterior segment. The anterior urethra is distal to the urogenital diaphragm and includes the bulbar and pendulous (penile) urethra. The posterior urethra is composed of the membranous (sphincteric) and prostatic urethra. The one constant landmark in fluoroscopic imaging of the urethra is the verumontanum, which is seen as an indentation in the membranous urethra. On oblique urethrogram, narrowing of the urethra may be seen as it traverses the urogenital diaphragm. The most distal aspect of the penile urethra is the fossa navicularis (the histologic convergence of urothelium and distal squamous epithelium) which is visualized as a slightly narrowed segment just proximal to the meatus.

The female urethra extends from bladder neck to introitus. The striated sphincter complex encompasses the distal two-thirds of the urethra. Dynamic contraction of the complex leads to urethral narrowing and has been mistaken for meatal stenosis in the past. Reflux into the vagina is frequently seen after voiding on urethrograms.

Voiding Cystourethrogram

The voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is the most effective method to dynamically image the urethra. Clinicians also use the VCUG to evaluate the upper tracts in cases where vesicoureteral reflux exists. A “cyclic” VCUG where the bladder empties multiple times is helpful to identify vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in duplicated systems. An anterior-posterior scout fluoroscopic image is first performed to evaluate for radiopaque stones and bony abnormalities, such as pelvic diastasis. It is our practice to use periprocedural antibiotics with gram-negative coverage and to obtain urinalysis and urine culture in select children prior to imaging.

An appropriately sized catheter is inserted into the bladder through the urethra or an indwelling suprapubic tube, without inflation of the catheter balloon. The bladder is drained and a urine culture obtained.

In males, the patient is placed supine with the penis laterally displaced for oblique images, while females remain supine for AP images. Iodinated contrast of an age and weight appropriate volume is instilled to opacify the bladder. Filling the bladder beyond predicted age and weight capacity may overestimate vesicoureteral reflux. The child then voids while monitoring with intermittent fluoroscopy. The voiding component evaluates the bladder neck for funneling and radiographic bladder emptying several minutes post-void. The appearance of the sphincter is monitored as the bladder neck begins to open at the initiation of voiding.

The VCUG provides essential imaging of the posterior urethra. Anterior-posterior images are obtained to evaluate the bladder and lateral/oblique images for the bladder neck and the urethra. Close communication between dedicated consistent radiology and urology staff is important for the best outcomes. Interobserver reliability may be poor, specifically when evaluating obstruction at the bladder neck and in the prostatic urethra in retrospective series [1].

Retrograde Urethrogram

The retrograde urethrogram—without voiding phase—is the preferred study to evaluate the anterior urethra, particularly in the male. For this study, a catheter is inserted into the fossa navicularis and the balloon partially inflated and placed on gentle traction to occlude the distal urethra. With the child in the lateral decubitus position, contrast is gently injected with slow steady pressure under fluoroscopy to overcome resistance of the external sphincter opacifying the posterior urethra as much as possible. In attempting to diagnose a suspected stricture to facilitate surgical planning, we try to opacify flanking aspects of the normal urethra by rotating the child or the fluoroscopy unit. To perform an adequate retrograde urethrogram in the shorter female urethra, a “double-balloon” catheter is sometimes used in adults to occlude both the meatus and bladder neck; this is not commonly used in children.

Newer Modalities

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used more commonly to image the upper urinary tract in children. Despite the use of triple-phased contrast-enhanced imaging (MR urogram) for functional imaging of the upper urinary tracts, a regular role for urethral imaging is yet to be identified.

Voiding enhanced urosonography is a newer imaging modality that reduces radiation exposure. This technique is under active investigation but has not yet been widely used [2]. Researchers have used it most often as an alternative to VCUG in children with suspected VUR. Nonlinear imaging techniques are used to differentiate anatomic structures from contrast-enhanced bubbles (galactose-palmitic acid) in this technique [3]. Transperineal imaging is used for males with a full bladder and normal micturition. Alternatively, the transpubic approach may be used to diagnose males with inability to control micturition and in females to better examine the bladder neck. Isolated reports describe the use of transpubic ultrasound to identify posterior urethral valves in two patients, and a dilated prostatic utricle and anterior urethral diverticulum were also diagnosed in two patients [4]. In a prospective comparison of VCUG and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in patients with suspected urethral pathology, ultrasonography accurately diagnosed posterior urethral valves, anterior valves, urethral stenosis, and detrusor sphincter dyssynergia in all. Two patients with syringocele were not identified with ultrasound but were diagnosed with VCUG [5].

While ultrasonography is useful for studying stricture length and depth in adults with anterior urethral strictures, we use it less in children. One study examined differences in echogenicity, luminal narrowing, and changes in periurethral tissue in non-contrast-enhanced ultrasound to diagnose anterior urethral stricture. The authors estimated the degree of urethral distention to determine stricture length. According to the authors, the use of perioperative ultrasound led to a change in planned surgical approach in 58 % of patients [6]. However, VCUG remains the study of choice for diagnosis of posterior urethral pathology.

Imaging of Acquired and Congenital Defects

Adequate imaging of the urethra is important for proper diagnosis of both acquired and congenital urological abnormalities. A wide range of congenital anomalies affects the urethra and requires urgent and repeated imaging. These include posterior urethral valves (PUV), prune belly syndrome, megalourethra, anterior urethral diverticula, anterior urethral valves, and urethral duplication. Acquired conditions may include trauma, strictures, diverticula, infections, urethrorrhagia, and sources of obstruction such as polyps or stones.

Congenital Urethral Anomalies

Congenital Urethral Polyps

Congenital urethral polyps arise from the verumontanum. They may result in bladder outlet obstruction in boys. Boys may complain of discomfort and straining to void. The diagnosis is usually made by VCUG, but polyps may be seen on ultrasound as well. The diagnosis is confirmed and the polyp is managed with cystoscopy and transurethral resection [7].

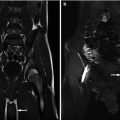

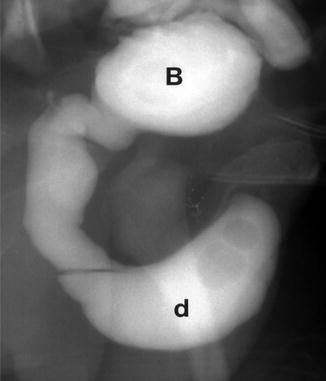

Posterior Urethral Valves (Fig. 15.2)

Fig. 15.2

Posterior urethral valves. (a) PUV showing dilated and elongated urethra. (b) PUV showing dilated and elongated urethra and multiple bladder diverticula. (c) PUV after valve ablation showing smooth transition across posterior urethra

PUV are the most common congenital cause of bladder outlet obstruction in children. A defect in the developing Wolffian duct folds is thought to be causative, and the valves become obstructive at variable times after the 8th week of development [8]. PUV are often diagnosed before birth—with ultrasound, with as many as 45 % of cases identified in utero [9]. Findings include a distended bladder often with bilateral hydronephrosis and a variable finding of oligohydramnios, depending on the severity of the obstruction and degree of renal injury. Postnatal renal bladder ultrasound (RBUS) and VCUG confirm the diagnosis. The sensitivity of RBUS in detection of valves is 95 % [10]. Findings of RBUS include a dilated, thick walled bladder often with diverticula/cellules, dilated upper tracts, and a dilated posterior urethra, the “key-hole” appearance. Urethral catheterization is the initial treatment prompted either by retention and/or ultrasound imaging.

VCUG/RUG is performed via urethral catheter or suprapubic tube, if present. The voiding phase is critical for differentiation from other forms of bladder outlet obstruction. While removal of the urethral catheter during the voiding phase is not always necessary, as it does not obscure the identification of the valves [11], our practice does remove the catheter unless contraindicated. Pathognomonic findings include the appearance of the valve which may be seen as an indentation on lateral imaging along with a dilated and elongated posterior urethra. Incomplete bladder emptying is also present. VUR is present in the majority of cases. After valve ablation, a follow-up imaging study is recommended in 4–6 weeks to assess decompression. If the degree of dilation of ureters and kidneys does not improved despite a decompressed bladder, a repeat VCUG could be performed to rule out residual obstruction.

Prune Belly Syndrome

Prune belly (Fig. 15.3) or triad syndrome (PBS) describes a triad of laxity of abdominal musculature, bilateral undescended testicles, and GU tract abnormalities, which include hydronephrosis, renal dysplasia, and urethral dilation. Variations of PBS may occur along a spectrum of these three clinical characteristics—so-called pseudo-prune belly syndrome [12]. Urethral dilation in PBS may arise from one of three etiologies. The first, urethral obstruction, occurs early in gestation and is believed to occur in 20 % of cases, from urethral atresia, urethral valves, or urethral diverticulum. Alternatively, the urethral dilation may be related to a functional abnormality of bladder emptying without obstruction. In the absence of an obstructive lesion, the dilation may result from prostatic hypoplasia. VCUG in PBS shows tapering of the dilated posterior urethra to the membranous urethra. A prostatic utricle is often present [13, 14].

Fig. 15.3

Prune belly with wide open bladder neck, dilated but short posterior urethra

Congenital Anterior Urethral Obstruction

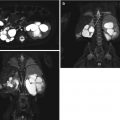

At least 260 reports have described cases of congenital anterior urethral obstruction, either congenital anterior urethral diverticula or anterior valves. Astute clinicians will suspect diverticula in boys with ventral penile swelling, post-void dribbling, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infection. When the diverticulum fills during voiding, it may progress to obstruction. Two forms of diverticula have been identified—saccular (Fig. 15.4) and globular. Diverticula are differentiated radiographically from congenital anterior valves by the presence of an acute angle between the proximal parts of the dilated urethra, which is not present with valves [15]. Iatrogenic anterior urethral diverticula may also develop after hypospadias repair due to distal obstruction and after repair of anorectal malformation if the rectourethral fistula is not trimmed close to the urethra. Diagnosis is made by VCUG/RUG.

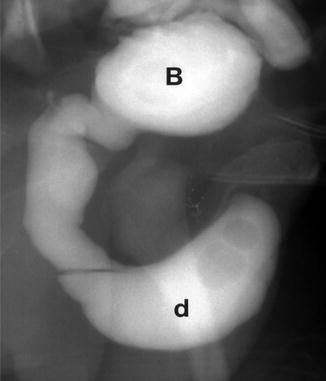

Fig. 15.4

Image from a VCUG of a boy with a saccular anterior urethral diverticulum. The bladder (B) is nearly empty, and contrast is seen in the posterior urethra and then filling the diverticulum (D)

Anterior urethral valves are a rare, obstructing condition of unclear embryologic origin. The valves originate close to the penoscrotal junction or bulbar urethra. They arise from the ventral portion of the urethra and obstruct urine flow during voiding. Many believe that valves are part of the spectrum of congenital urethral diverticula. Indeed, valves may develop into diverticula secondary to outflow obstruction. However, pathologic findings indicate that congenital valves are always bordered by the corpus spongiosum and true congenital urethral diverticula develop outside the corpus spongiosum [16]. The gold-standard diagnostic study remains VCUG/RUG; however, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has been used to make this diagnosis.

Urethral Duplication (Fig. 15.5)